Introduction

In the past twenty years, a series of profound technological developments has impacted education. Newly emerging technological tools, applications, and online learning environments present opportunities and possibilities for peers to collaborate in new ways, irrespective of location. As seasoned educators, we have experienced the shift towards online learning in the form of blended and flipped classrooms as well as fully online, credited courses. An integral part of this shift is the role online tools play in facilitating learning, and how the implementation and use of these tools impacts instructional design and online pedagogy. As practitioners, we experiment with online tools to establish what does and does not work in a given learning context. This is important work. However, as educators we also have a responsibility to ensure learning theory and research inform our decision making when planning, reflecting on, and evaluating curriculum tasks, activities, and pedagogic practices.

In this paper we examine a sample media studies unit within a constructivist learning theory framework to show how Google Drive tools can be used as an effective online learning environment (OLE). Although Google tools have been discussed here in JITP and in other reputable publications such as Kairos, the aim of this paper is to illustrate how modern online pedagogic practice and tools connect to key founding theories of constructivism and online learning. The sample media studies unit is a culmination of years of iterations and reflection on the delivery and efficacy of media lessons online. The Ontario Media Studies grade 11 course curriculum is used to illustrate how various Google Drive tools provide the appropriate affordances to facilitate constructivist online learning. While this is an elective course for Ontario students, each grade in the secondary school curriculum contains a media studies strand in the mandatory English curriculum, hence the unit can be adapted for Ontario English courses. It is our hope that in sharing this sample unit and accompanying theory, other educators can learn from, adapt, and build on our work for their own use, not only in media-related courses, but in other subject areas as well. Prior to this, an overview of some of the more pertinent constructivist theories and approaches used in the design of the Google online learning environment (GOLE) is provided.

The Theory behind the Practice

Highly influential constructivist education writers and researchers (Dewey 1916; Piaget 1973; Vygotsky 1978; Bruner 1996) all agree that active learning and the construction of new knowledge is based on prior knowledge, and that the role of the instructor is that of facilitator. Moreover, Dewey (1916) argues that the improvement of the reasoning process is a key function of education. Indeed, utilizing problem-solving methods on personally meaningful and real life problems can act as motivation for students, engaging them in process of discovery. With this in mind, the design plan for our GOLE ensures students have every opportunity to utilize their critical thinking skills and prior knowledge, while making personally relevant choices about what topics and themes to investigate in the media studies unit.

Dewey (1938) also argues that interaction is one of the most important elements of a learning experience and that “an experience is always what it is because of a transaction taking place between an individual and what, at the time, constitutes his environment…” (Dewey 1938 cited in Vrasidas 2000, 1). The GOLE design acknowledges the reciprocal nature of learning interaction and the variety of relationships and communicative exchanges required to facilitate meaningful learning (Simpson & Galbo 1986). As the teacher facilitates activities throughout the course, they should consider the nature and types of interaction present in learning environments: learner-learner, learner-teacher, and learner-content (Moore 1989), as well as the ways these interactions translate to an online learning environment. This social constructivist approach stresses the critical importance of interaction with others in cognitive development and emphasizes the role of the social context in learning (Huang 2002).

Vygotsky (1978) details the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and explains how important social interaction is in the psychological development of the learner. Vrasidas (2000) describes the ZPD as, “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (10). The GOLE features afford students multiple opportunities to learn with others and advance their knowledge through collaboration, working with a variety of learners in different activities using a selection of Google Drive tools.

Class Introduction, Overview of Media Studies Unit, and Expectations

The proposed unit for a media studies course is based on best practices and pedagogy from previous media studies lessons conducted in online learning environments. A Grade 11 English Media Studies course from the Ontario Curriculum is the site of this unit. Figure 1 provides a breakdown of the unit sections and related objectives/expectations.

| Unit Sections | Unit Objectives |

|---|---|

| A. Understanding and Interpreting Media Texts | 1. Understanding and responding to media texts:

– demonstrate understanding of a variety of media texts; 2. Deconstructing media texts: – deconstruct a variety of types media texts, identifying the codes, conventions, and techniques used and explaining how they create meaning. |

| B. Media and Society | 1. Understanding media perspectives:

– analyze and critique media representations of people, issues, values, and behaviors; 2. Understanding the impact of media on society: – analyze and evaluate the impact of media on society. |

| C. The Media Industry | 1. Industry and audience:

– demonstrate an understanding of the ways in which the creators of media texts target and attract audiences; 2. Ownership and control: – demonstrate an understanding of the impact of regulation, ownership, and control on access, choice and range of expression. |

| D. Producing and Reflecting on Media Texts | 1. Producing media texts:

– create a variety of media texts for different audience; 2. Careers in media production: – demonstrate an understanding of roles and career options in a variety of media industries; 3. Metacognition: – demonstrate an understanding of their growth as media consumers, media analysts, and media producers. |

Figure 1: Grade 11 English Media Studies from the Ontario Curriculum

Overall expectations addressed in the proposed unit include:

- Industry and Audience: demonstrate an understanding of the ways in which the creators of media texts target and attract audiences.

- Producing Media Texts: create a variety of media texts for different audiences and purposes, using effective forms, codes, conventions, and techniques.

- Metacognition: demonstrate an understanding of their growth as media consumers, media analysts, and media producers.

- Deconstructing Media Texts: deconstruct a variety of types of media texts, identifying the codes, conventions, and techniques used and explaining how they create meaning.

- Understanding and Responding to Media Texts: demonstrate understanding of a variety of media texts. (The Ontario Curriculum Grades 11-12: English, 2007)

The Online Learning Environment: Why Google Drive?

When thinking about designing a constructivist OLE it is useful to consider how social constructivist theory can inform which tools to include in it. Vygotsky (1978) argues that people socially construct meaning and cultural norms and that learning is situated. Lave and Wenger (1991) suggest implicit and explicit knowledge is acquired through legitimate participation in situated communities of practice (CoP). Learners participate on the periphery of an activity within a CoP and as they participate and learn they become more knowledgeable. This enables them to move, if they wish, towards the center of the CoP and play a larger role in the communities’ activities. The central idea of situated learning is that learners appropriate an understanding of how to view meanings that are identified with the CoP, and that this process forms a learner’s identity within the learning community. For example, to become a television production assistant a person must appropriate the skills, values, and beliefs required in the practice of working in the television industry.

Hung and Chen (2001) provide a number of design considerations related to situated learning that can help learning designers decide what tools need to be included in an OLE to best support constructivist learning. They argue situatedness can be fostered by contextualized activities that encourage implicit and explicit knowledge acquisition such as projects based on the demands and requirements of the course curriculum. Furthermore, students need to be able to access their OLE in their situated contexts at any time and preferably on portable devices.

Hung and Chen (2001) suggest students also need to learn through reflection and internalize social learning through metacognitive activities such as journaling and asynchronous discussion. Google Drive is available online on portable devices and includes the weblog (blog) software Blogger in its suite of applications. Blogs can be used as interactive online journals, which can be personalized by the learner and used for important metacognitive reflective activities essential for deep learning (Sawyer 2008).

Also as Bereiter (1997) argues, electronic records of learners engaged in discourse on networked computers produce significant knowledge artifacts in and of themselves. These knowledge artifacts are essential for educators because “knowing the state of a learner’s knowledge structure helps to identify a learner’s zone of proximal development” (Boettcher 2007, 4); which in turn allows educators to understand where and when learner scaffolding is required within the OLE.

Hung and Chen (2001) also introduce the concept of commonality, the idea that learning is social and identity is formed through language, signs, and tools in CoPs. They explain that commonality can be fostered through learners having shared interests in books, for example, or having shared assignment problems. Learning designers can leverage commonality and embed tools in their OLEs that enable students to communicate and collaborate on their common interests.

Google Drive has several tools that enable collaboration through computer mediated discourse. These tools include Google Messenger (synchronous and asynchronous text and video messaging), Google Circles (synchronous and asynchronous text messaging and multimedia sharing), and Google Hangouts (synchronous video chat with up to nine people at once, face-to-face-to-face). The interactive nature of blogs also allows them to be used for communicating and sharing ideas within online CoPs. In terms of assessing student engagement and interaction, the revision history tool in Google Docs allows teachers to follow the contributions of each student by observing their writing and editing process, as well as the comments they post to their peers.

Google Drive has several other tools suitable for the online administration of courses. Gmail, the email application, can be used for formal teacher-student correspondence and the distribution of grades and other important announcements. Google Calendar is suitable for updates about the syllabus and deadlines and alerts regarding the course. Google Docs can be used to construct online surveys and polls, often used by constructivist educators to allow learners to vote on aspects of the course they would like to change in some way or for students conducting research of their own. In addition, Google Drive folders can house the course documents; the syllabus, readings, FAQs, and sign up forms can be accessed and updated from anywhere at any time. Student folders can be created on Google Drive for students to upload their work. Educators can use Google Hangouts to discuss group work in online video conferences. Furthermore, YouTube (part of Google) is an ideal platform to present digital artifacts that illustrate project based learning. The affordances Google Drive technology provides learners are numerous (see figure 2).

Quinton (2010) notes that it is essential for student learning that dynamically constructed learning environments be customized to meet the preferences and needs of individual learners in OLEs. The integrated nature of Google Drive enables all course communication, discussion, administration, and student work presentation to be fully integrated and customized to the learners’ needs. Users can personalize their settings and receive updates and notifications about all activity on the course. The GOLE enables students to communicate informally, fostering social presence, either by using one-to-one synchronous messages on Google Messenger, or by setting up their own Google Circle for group chat.

Formal discussions and reflection are afforded by Google Circles, Google Hangouts, and Blogger. Note, Google Hangouts enables synchronous video conferencing. This affordance is particularly useful for teaching and learning because OLEs often do not enable the interactants to see one another’s paralanguage, making the possibility of misunderstanding common, particularly for people from different cultural backgrounds (Dillon, Wang, & Tearle 2007).

Educators and groups of students can see, hear, and talk to each other at scheduled times using Google Hangouts, which has the potential to really boost the social, teaching, and, subsequently, the cognitive presence on GOLE courses. Students have numerous customizable applications to compose and display their learning, such as the Blogger, YouTube, and Google Presentation applications as well as word processing, drawing, and spreadsheet software. All these applications empower users to share and collaborate with each other and determine who can see and contribute to whatever they are working on prior to when it is presented for feedback. Used appropriately, the tools in Google Drive facilitate distributed constructionism, whereby learner knowledge emerges from the distributed discourses and knowledge artifacts they have access to in their OLE (Salomon 1994).

Administration and Unit Plan

From our experience teaching in OLEs, we conceive three key objectives at the course start: acclimatizing students to the online environment, establishing a community of learners, and making explicit the goals and objectives of the course. Early peer to peer and peer to instructor interaction is essential because, as Garrison & Arbaugh (2007, 60) point out, “it takes time find a level of comfort and trust, develop personal relationships, and evolve into a state of camaraderie.” Furthermore, positive social climates promote the rapid mastery of the hidden curriculum and enhances group tasks, self-disclosure, and socio-emotional sharing (Michinov, Michinov, & Toczek-Capelle 2004).

Therefore, one of the first activities in our unit plan requires students to create a biography using general questions and prompts from the teacher, and to share it using Google Docs. For example, we incorporate a simple media studies-related icebreaker using threaded discussions. Students post to the discussion board three personality traits, three favorite television shows, three favorite musicians, and three most used websites. Students are then asked to find at least three other students they have something in common with and write a response. In our experience, sharing commonalities and interests builds rapport and community in peer groups, particularly if this is done at the start of the course.

At the same time, educators must be mindful of critical pedagogy and how identity can play out in online environments. While the opportunity for disembodiment and the de-emphasis on race, class, and gender in virtual environments can lead to many positive possibilities, caution is warranted. As Dare (2011, 3) argues “the constitution of the online classroom as a color-blind space free of raced and sexed bodies is one which deserves greater reflection by examining the implications of ‘disembodying’ students and instructors in the virtual classroom, within the context of classes about race, gender, and globalization.” Such awareness is a necessity and instructors should work to create an inclusive, supportive, and non-threatening community. We have found the best practice is to allow each student to regulate how and what they choose to share about their identity with their peers over time.

During the first week, students are asked to watch an introductory YouTube video created by the instructor using screen capture software such as Jing. The video serves to welcome students and provide a virtual tour of the Google Drive platform, which assists students in locating administrative information to begin the course. All Administrative documents (course outline, assessment and evaluation information, online etiquette, and so on) need to be detailed and explicit to reduce uncertainty, and they should remain in one Google Doc folder for easy reference.

In the administrative section, students should also have access to their grades and feedback through the Google Spreadsheets feature. Students require opportunities to play an active role in their learning process and self-evaluation, through the negotiation of course objectives, content, and evaluation. In previously taught courses, our students have written reflections alongside the teacher-produced grade reports, putting the onus on students to take responsibility for their progress and next steps. Active participation, a central tenet of constructivism, increases the likelihood of embracing and accomplishing tasks used to facilitate learning (Vrasidas 2000).

Finally, a section for technical help should be made available to students using the Google Communities feature. Here, students can post questions and discuss technical issues they may be facing with Google Drive tools, allowing them to collaboratively diagnose problems and find solutions. In our courses, we encourage students to ask course and technical questions in the group forums rather than emailing the instructor. Doing so allows an opportunity for other students to come forward and support others with their knowledge, while also reducing repetitive emails to the instructor with the same questions. This feature “connect[s] people to people and information, not people to machines[,]” and enables students to “engage in collaborative knowledge production and facilitation of understanding—in effect, a connected network of mentors/ interest /practice” (Quinton 2010, 346-47). A high level of teacher presence is required at this stage to monitor the OLE and ensure that any outstanding issues are fully resolved in a timely manner.

Sample Unit Plan: Our Mediated Environment

The sample unit provided below highlights the type of lessons, activities, exercises, and assignments students engage in throughout the course. (Some lesson plans have been adapted from curriculum materials freely available at Mediasmarts.ca and the Association for Media Literacy).

Part One: Marketing to Teens

Throughout the first unit (3-4 weeks), the teacher should moderate class discussions, and explicitly model some of the skills, strategies, and critical thinking techniques that students will need to acquire for moderating future class discussions. As Vrasidas (2000) points out, “having students work in groups to moderate discussions, organize debates, summarize points, and share results will help them achieve their full potential” (10). Following the first unit, pairs of students should select a week to moderate the discussions (based on a topic/ theme of interest) in partnership with the teacher.

In addition to modeling discussion-moderation techniques, the teacher can provide a tip sheet of strategies and offer constructive feedback during their moderation period. As Brown, Collins, and Duguid (1989) conclude, “to learn [how] to use tools as practitioners use them, a student, like an apprentice, must enter that community and its culture. Thus, in a significant way, learning is […] a process of enculturation” (33). Furthermore, research demonstrates that teacher presence plays an important role in enabling students to reach the highest levels of inquiry (Garrison et al. 2001; Luebeck & Bice 2005).

Lesson 1

Students are assigned two readings online: How Marketers Target Teens and Advertising: It’s Everywhere (Media Smarts n.d.) to introduce concepts such as psychology and advertising, targeted advertising, building brand loyalty, ambient and stealth advertising, commercialization in education, and product placement. Students begin the first threaded discussion using Google Circles with a series of questions and prompts regarding the ubiquitous nature of advertisements targeted at youth. For example, guided prompts might ask questions such as “why are youth important targets for marketers?” “how do marketers reach teens?” or “which media advertisements do students feel have the greatest appeal and why?” The quality of guiding questions directly impacts the quality of responses and interactions between students. As evidence shows, the questions initiating online discussion also play an important role in the type of cognitive activity present in online discussions (Arnold & Ducate 2006).

Activity 1: Research

For this activity, students take a 10-15-minute walk in their local neighborhood, and they note the type and location of all advertisements they encounter (on bus shelters, billboards, newspaper boxes, bike racks, people’s clothes, shopping carts, buses, and so on). They then share their Google Map coordinates and a screenshot to highlight their selected route and share their findings with the rest of the class using Google Presentation. Students then form groups of four in a threaded discussion group to further examine one another’s Advertisement (Ad) Walks. Throughout this activity, students should be encouraged to use a selection of knowledge sources such as libraries, museums, and email exchanges with industry professionals. Asking students to engage in learning with activities such as Ad Walks places them in the center of their learning so “teachers will no longer be [seen as] the only source of expertise” or the only resource (Sawyer 2008, 8). Next, students are asked to consider the target audience for the ads and speculate on the rationale for the location of advertisements (i.e. advertisements targeted at teens are often located close to high schools and shopping malls). In a threaded discussion with teacher prompts, students should have an opportunity to examine the difference in advertising tactics on reservations, in rural, suburban, and urban environments; hence sharing “their situated experiences and knowledge with one another (Dare 2011,10).

Dewey (1916) argues that learning results from our reflections on our experiences as we endeavor to make sense of them; therefore, students should also be asked to compare and comment on the extent of media advertisements in their own homes (internet, television, magazines, radio etc.) and reflect on their findings using the blog and guided questions prepared by the teacher. The teacher should also ask students to read at least two student blog posts and to post comments on each other’s reflections. This activity is intended to increase student motivation and provide authenticity to the learning process, as students will know that there is an active online audience for the online artifacts they are creating (Resnick 1996). The use of technology and other cultural tools (to communicate, exchange information, and construct knowledge) is fundamental in constructivism because as Vrasidas (2000, 7) argues “knowledge is constructed through social interaction and in the learner’s mind.”

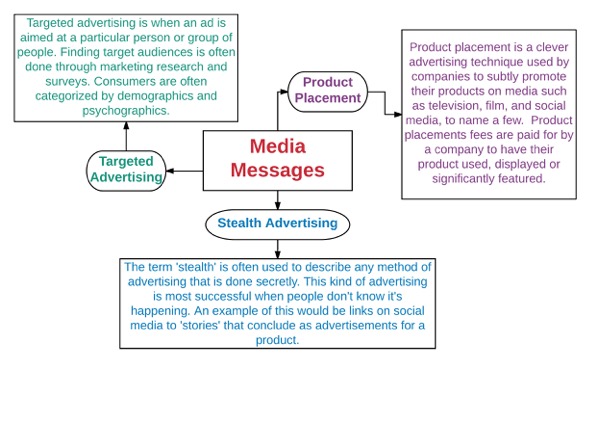

Activity 2: Connecting Media Concepts

At the beginning of the course, students should be given the choice to select a unit that holds particular interest to them. In small groups (3-4), they are then given the responsibility for creating a mind map that demonstrates the connections and intersections of new concepts they have been exposed to. Using a mind map, the student groups work collectively to define each of the concepts and identify and illustrate connections among meanings. For example, the unit highlighted in this paper introduces stealth advertising and product placement. These concepts can be connected by their approach; both are non-traditional forms of advertising and are often embedded in other forms of media that contain covert messaging (see figure 3 for student exemplar). Mind mapping tools such as Lucidchart can be located in Google Docs add-ons. Teachers are encouraged to review all the add-on features and extensions that will best suit the needs of their students.

Figure 3. Mind map student exemplar that demonstrates the connections and intersections of new concepts they have been exposed to.

This ongoing constructed resource shifts and grows throughout the course as students manipulate the document to build new meanings together. This nurtures the collective cognitive responsibility of the class, whereby “responsibility for the success of a group effort is distributed across all the members rather than being concentrated in the leader” (Scardamalia 2002, 2). The students are made responsible for their own learning and should ensure that their classmates “know what needs to be known” (ibid.). This is a particularly effective way for knowledge-building communities to form and grow because collaborative activities need to involve the exchange of information and the design and construction of meaningful artifacts for learners to construct and personalize the knowledge (Resnick 1996). To consolidate and distribute learning, this activity should be repeated for each of the five units in the course.

Part Two: Decoding Media Messages

Lesson 2

In this lesson, students explore the values and beliefs hidden behind advertising messages by analyzing a selection of print, audio, and video advertisements. Students watch an introductory video on “values and media messages” on YouTube (created by the teacher). The teacher video should contain an explanation of how the two media frameworks used throughout the course (The Eight Key Concepts of Mass Media and the Eddie Dick Media Triangle; See figure 4) and how they pertain to decoding and deconstructing advertising and marketing messages. The video provides an introductory explanation of the concepts being discussed in the course and adds important elements of teaching presence such as focusing discussion, sharing meaning, and building knowledge (Garrison et al. 2001). Both frameworks should be made available in the class Google Docs folder titled Administration.

To further their understanding of the constructed nature of media advertisements, students are also asked to watch the Dove Evolution Commercial on YouTube, along with one of the parodies for the Dove Evolution Commercial that can also be found on YouTube. Using their online journals, students then write a reflection on their personal reaction to both the commercial and a Dove parody video, and then identify some of the key elements found on the Media Triangle to arrive at intended and unintended meanings. Online journaling is considered an aspect of cognitive presence, defined as “the extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse” (Garrison & Arbaugh 2007, 161) in which students work through the stages of inquiry and arrive at their own meanings through reflective practice.

Figure 4: The Key Concepts of Mass Media and the Eddie Dick Media Triangle. Adapted from http://frankwbaker.com/mediatriangle.htm

Activity 3: Group Presentation

Through discussion in small groups using Google Circles, students deconstruct one advertisement of their choice to be presented to the class using the prompts on the Media Triangle handout. The objective is for students to deepen their awareness and understanding about the explicit and implicit values and meanings associated with their selected advertisement. The use of Google Circles enables the teacher to view what is being discussed and provides the necessary scaffolding (Vygotsky 1978) for the learners to continue to extend their ZPD. Furthermore, working in groups on collaborative activities facilitates social presence in online courses as it enables learners to “project themselves socially and emotionally” (Garisson & Arbaugh 2007) and develop a sense of community and improve and practice “real life” working relationships in online courses.

Using Google Presentation feature, students upload their work in a shared folder in Google Drive for the rest of the class to evaluate. In an asynchronous exercise, students are asked to view all presentations (about 4-5) and offer a critique for each work in Google Circles. Having peers critique group presentations produces further insights/perspectives the group may have overlooked or not recognized. As a result, students are more likely to gain a deeper understanding from “the expertise (knowledge and skills), perspectives and opinions” of their peers and “draw from each other’s strengths” and “make use of each other’s abilities” (Hung & Chen 2001, 7) to help construct knowledge.

Activity 4: Reflection

Using their blogs, each student repeats the process of activity 3 using a media advertisement that has personal relevance or meaning. Students also respond to guided prompts such as, “Explain one way the advertisement communicates to its audience and what one resulting meaning is for you.” Dewey states that “learning results from our reflections on our experiences, as we strive to make sense of them” (Russell 1999, 2); and through reflection, students “externalize and articulate their developing knowledge, [and] they learn more effectively” (Sawyer 2008, 7).

Activity 5: Parody Advertisement Media Production

In this activity, students work either in pairs, independently, or in a small group to create of a parody advertisement. Using their new knowledge about advertising strategies and their understanding of the media construction frameworks from prior activities, students deconstruct one parody advertisement and then create their own media artifact with a focus on branding: for example, a parody print advertisement of their own, a short commercial, a radio jingle, or an audiovisual slideshow.

To introduce the concept of branding, students view a four-minute segment of the award-winning Canadian documentary, The Corporation. In this segment, Canadian activist Naomi Klein discusses the impact of corporate branding on individuals and culture (Note: This YouTube video is a legal chapter segment shared online by The Corporation Director Mark chbar). In a threaded discussion on Google Circles, the teacher prompts discussion by asking students what comes to mind when they hear the terms ‘brand’ or ‘branding,’ and what they think about the video.

Students should also be provided with the following definitions:

Branding: the process involved in creating a unique name and image for a product in the consumer’s mind, mainly through advertising campaigns with a consistent theme. Branding aims to establish a significant and differentiated presence in the market that attracts and retains loyal customers. (Business Dictionary, n.d.)

Corporate branding: An attempt to attach higher credibility to a new product by associating it with a well-established company name. Unlike a family-branding (which can be applied only to a specific family of products), corporate branding can be used for every product marketed by a firm. (Business Dictionary, n.d.)

As a class, students examine the iconic brand Nike. The teacher forms small groups of students who have not yet worked together and these groups develop responses to the following questions adapted from lessons available on the Association for Media Literacy (AML) website. This can be completed on a collaborative document in Google Docs and later transferred to the threaded discussion to share with the rest of the class. Students respond to the following prompts:

- List the positive (intended), neutral, and negative values/ messages that come to mind when considering the brand, Nike. (Responses may range from: cool, stylish, youthful, attractive, wealthy, iconic, patriotism and child labor, mass production and the environment, human rights violation, etc.).

- Using the Media Triangle framework, how does Nike portray their intended values?

- How have you been informed about the neutral and negative values?

When students have completed the responses in their small groups, they share their findings with the rest of the class on the threaded discussion and respond to other groups.

Students will then explore the concept of parody advertisements using a Nike Adbusters parody advertisement (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Nike vs. Tiger Woods: Image shows two different photographs of Tiger Woods. Adapted from: http://www.adbusters.org/spoofads/unswooshing/

As a reflection assignment to be completed on their blogs, the teacher asks students to consider the following statement from the Association of Media Literacy:

Parody advertisements are a fun way to analyze popular advertisements, especially advertisers who are selling products, which have social and political implications. When you spoof an advertisement, you take elements of the message that give it power and turn the message around to show that it is ridiculous or even untrue. (Association for Media Literacy, March 25, 2017)

Reflection Questions:

- What elements make this a parody advertisement?

- What was the first thing you noticed about the advertisement, what is being made fun of? Why is humor an effective way to make a point?

- What elements are different or the same compared to the real advertisement? (see codes and conventions on Media Triangle Framework)

- Does the parody advertisement change how you perceive the original advertisers?

- What is the value message in this parody advertisement? If you could write a statement message for the parody advertisement, what would it be (2-3 sentences)?

To further distribute knowledge, learning, and social and cognitive presence, students are then asked to comment on a student blog they have not visited during the course. As Cole and Engestrom (1993, 15) reason, one person cannot contain all the knowledge or culture of the group that they identify with, thus knowledge can and should be, “distributed among people within a cultural group.”

With background experience in branding and the parody advertisement critique experiences now in place, students are well prepared for the final activity: the creation of a parody advertisement. Students form groups or pairs based on their personal interests (radio jingle, video, magazine advertisement, website etc.). As Resnick (1996) argues, when personally meaningful artifacts are constructed, new knowledge is constructed with greater effectiveness. Students should be encouraged to use freely accessible Google+ applications such as Pixlr (image editing), UJAM (audio editing) and Magisto (video editing). By having students use popular applications from their own cultural context, the task is rendered more authentic, lessening the often ‘transmuted’ activities students may experience in school (Brown, Collins & Duiguid 1989). Student groups create a Google Community to carry out the following tasks:

- Select a brand to spoof (ideas can be found on Adbusters website)

- Identify the intended values and value messaging of the brand and their advertisements

- Select the new value message the group wishes to convey and create a slogan or tagline

- Using Google+ applications and tools, create parody advertisement in the Google Community.

Once the parody advertisements have been completed, each group signs up for a synchronous video conference with the teacher using Google Hangouts (up to nine participants) to take part in a group critique of their work. Students working independently can be grouped into one critique group. Other students will be encouraged to attend the Google Hangouts session which should also be recorded for students who wish to view the critique afterwards, as well as for teacher evaluation and assessment.

Conclusion

This paper has considered online learning from a constructivist perspective and applied a selection of the key concepts and ideas of influential constructivist thinkers to the design of an online media studies course for 11th graders studying in Ontario. The affordances Google Drive offers to constructivist pedagogic practice have been shown to be numerous. The integrated nature of the suite of applications and the communication, sharing, presentation and administration possibilities the software affords educators planning an online course make Google Drive a very useful pedagogic tool. The central idea of constructivism—that knowledge is constructed in people when incoming information meets and integrates with their existing experience and knowledge—has been discussed and illustrated using authentic current curriculum documents and teaching activities.

To encourage and facilitate constructivist learning, well thought out, student-centered learning tasks and activities that leverage the various affordances of the technology need to be devised, monitored, reviewed, and added to, to ensure the learning experiences of students and educators constantly extend. The construction of knowledge is both an individual and group endeavor that changes from moment to moment and from an educational perspective from course to course. Individual learners that make up the community of any course shape its conversations, its direction, and consequently the learning that happens within it. The fluid nature of this kind of learning makes it an engaging and stimulating way to learn. It is the work of online learning designers to ensure that when they are making pedagogical decisions that they fully exploit the affordances of the technology they use to promote student-centered activities that nurture and sustain learner engagement and stimulation.