Introduction

In the summer of 2016, the world was introduced to the emerging technology of augmented reality (AR) in the form of Pokémon Go, a location-based, AR-enhanced game that became one of the most popular mobile apps of the year. Many people were already familiar with virtual reality (VR), “a medium composed of interactive computer simulations that sense the participant’s position and actions and replace or augment the feedback to one or more senses, giving the feeling of being mentally immersed in the simulation (a virtual world)” (Sherman and Craig 2003, 13). As a popular gaming environment, VR has four key elements: it is a virtual space for the participant; it is immersive on both a physical and mental level for the participant; it provides sensory feedback directly to the participant; and it is interactive, responding to the participant’s actions (Sherman and Craig 2003, 6–11).[1] VR, in its most effective form, requires the user to be isolated from a conscious awareness of the real world by some sort of head-mounted display, such as Oculus Rift, Microsoft HoloLens, or HTC Vive. Alternatively, the user can experience VR in an enclosed, projection-based or flat-monitor-based environment, such as a CAVE.[2] Typically, the experience must be held in a static, controlled space; otherwise, the user might collide with real-world objects in the effort to participate fully in the virtual world. And, for many individuals, the VR experience results in motion sickness, sometimes known as VR sickness or cybersickness.[3] In contrast, AR is a medium in which digital information is overlaid on the physical world that is in both spatial and temporal registration (i.e., alignment) with the physical world and that is interactive in real time (Craig 2013, 36). Consequently, AR is much more accessible because the required equipment, usually a smart device (iPad, iPhone, Android tablet, or Android phone), is minimal. The fact the user remains cognizant of the real world around them while using the technology reduces the possibility of motion sickness and does not typically limit the user to a static, controlled space for the experience.

Both technologies have applications beyond gaming and are proving particularly effective and engaging for historic recreations. Such recreations can have a significant impact on learning, for they engage viewers—both the general public and students—in an educational immersive experience. Many of these viewers may never visit the actual historic site in their lifetime, so accuracy is important. Consequently, we need to keep in mind that a 3D digital model is a re-creation and not the real place. And as we move forward with VR and AR, we must give serious consideration to the goals we need and/or wish the technologies to meet, particularly with respect to pedagogy. At this point in time, VR and AR are very successful in engaging audiences for both entertainment and educational purposes:

The increasing development of VR technologies, interfaces, interaction techniques and devices has greatly improved the efficacy and usability of VR, providing more natural and obvious modes of interaction and motivational elements. This has helped institutions of informal education, such as museums, media research, and cultural centers to embrace virtual technologies and support their transition from the research laboratory to the public realm. (Rousso 2002, 93)

For the user visiting a virtual heritage site, the experience can be highly engaging and educational as long as expert guidance is provided. VR and AR cannot substitute for pedagogical instruction. It is not so much that the user must be reminded that the virtualization is not real; rather, supporting documentation must be easily accessible within the virtual world to help the participant understand the meaning and significance of the 3D models they encounter. And content builders must take an interdisciplinary, if not transdisciplinary, approach to the creation of the 3D models and their VR- or AR-enhanced worlds if the learning experience of the participant is to be as significant and valuable.

These technologies have the promise not only of engaging students in the history itself, but also of inviting them to consider how the work of history is done. As scholars and experts, we require the 3D models and their environments to be historically accurate, but that accuracy is necessarily limited. All models are inevitably interpretations of available evidence, and making that process more transparent to the student leads not only to a better understanding of the subject matter but of the process as well. As Willard McCarty has noted,

The best model [e.g., digital humanities tool] of something, that is, comes as close as possible to what we think we know about the thing in question yet fails to duplicate perfectly that knowledge. Failure of the model in an engineering sense is its success as an epistemological instrument of research, because skillfully engineered failure shows us where we are ignorant. (McCarty 2003, 1232)

Failing to create the perfect 3D model of an object in terms of historical authenticity is to be expected and appreciated for what it can teach us not just about the technology but about the 3D model itself in terms of our understanding of its historic accuracy. As teaching tools, VR and AR force the historical experts, as content creators, and their students, as content consumers, to think very carefully and intentionally about the recreation. For example, precise verisimilitude of a medieval English village could only be achieved by travelling back in time to the Middle Ages to conduct the kind of fieldwork envisioned by Connie Willis in her 1992 science fiction novel The Doomsday Book—an unlikely prospect by anyone’s standards.[4] However, it is important that we think beyond what VR and AR can do today. Even if we fail to achieve what we want the technology to do, we will learn from our mistakes and, in so doing, improve both the technology and our students’ understanding of the historical method.

Historical Accuracy: A Theoretical Approach

Virtual constructions of historical objects and architecture raise very real concerns about verisimilitude. To what extent are such 3D models accurate representations of the original? In many ways, VR serves to validate Jean Baudrillard’s understanding of simulacra and concerns about the hyperreal. In Simulacra and Simulation, he argues that the loss of distinction between reality and its representation results in the hyperreal—a world “without origin or reality” (Baudrillard 1994, 1–7). It is pure simulation and, as a result, creates an anxiety of origin and authenticity. Virtual worlds, including those associated with VR, can evoke an apprehension about the hyperreal, especially if the 3D model is used to substitute for the original. The current interest by computer graphic experts and enthusiasts in the creation and redistribution of virtual historic sites illustrates the problem. “Archaeological illustration and reconstruction is not new,” as Clifford L. Ogleby notes,

but the advent of high-speed affordable computers and the associated graphics capability gives people the opportunity to create better looking imagery. The imagery, however, is often the result of the technology, not archaeological or historical research. When this imagery is distributed without the accompanying research that explains the decisions made in the reconstruction, it is open to a variety [of] interpretations. This problem is compounded when the imagery is posted on the [world wide web], as the image can be extracted from the surrounding text and interpreted as an artifact rather than as a diagram. (Ogleby 2007)

Ogleby demonstrates this issue using easily obtainable images from the web that purport to portray accurate reconstructions (some computer generated) of the mausoleum at the ancient Greek city of Halicarnassus.[5] The images are imprecise and even erroneous, yet accepted by the general public as real: “Many people will tend to ‘see’ a photo-like image to be more like a photograph, and therefore a record of a real place in time” (Ogleby 2007). Not surprisingly, these online images almost always fail to include provenance, authorship, and veracity—information that would help the viewer to determine the authenticity of each 3D model and would serve as a reminder that the image being viewed is just that, an image, and not the original. The problem is only exacerbated when these models are incorporated into a virtual environment such as Google Earth or Second Life (Ogleby 2007).[6] These immersive and interactive worlds can encourage the non-expert user, such as a student, to accept the computer-generated model as an overly realistic recreation of the original.

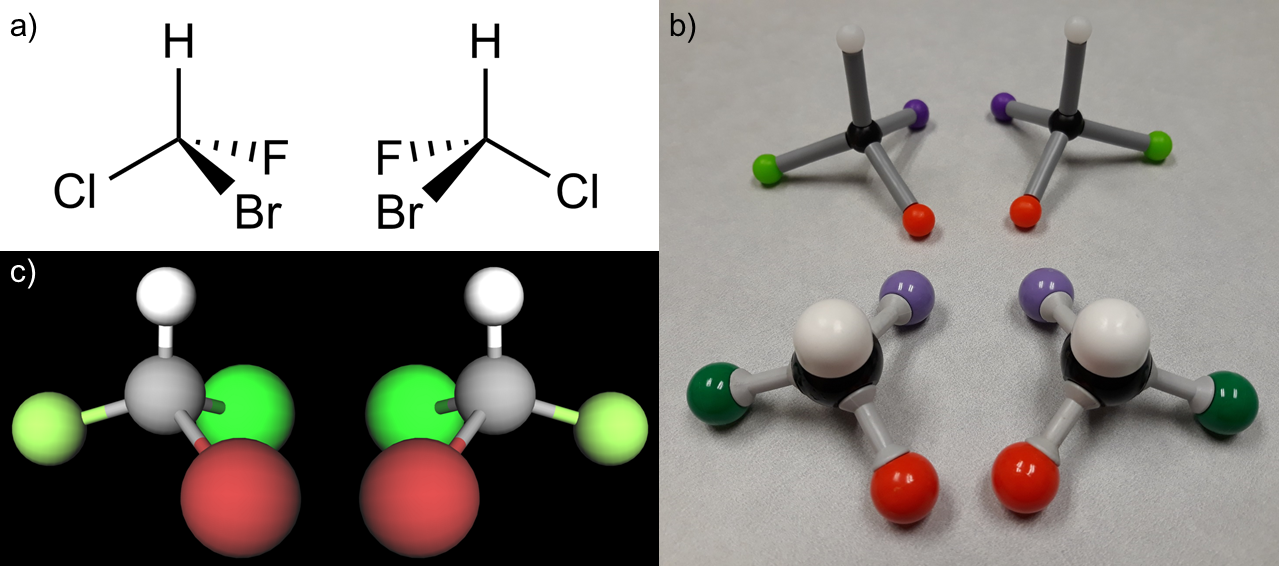

Nevertheless, we should not be dissuaded from using the technology for pedagogical purposes both in the classroom and the community at large. Pierre Lévy argues convincingly against viewing the virtual as simply unreal: “The virtual, strictly defined, has little relationship to that which is false, illusory, or imaginary. The virtual is by no means the opposite of the real. On the contrary, it is a fecund and powerful mode of being that expands the process of creation, opens up the future, injects a core of meaning beneath the platitude of immediate physical presence” (Lévy 1998, 16). It is an actualization rather than a realization, one that involves “the production of new qualities, a transformation of ideas, a true becoming which nourishes the virtual in a feedback process” (Lévy 1998, 15).[7] The virtual and the real are not binary opposites. Rather, they exist on a continuum that supports a complete range of realness from the fully real to the fully virtual. Such a reality-virtuality continuum was first proposed by Paul Milgram and his colleagues. They suggest that everything in between is a mixture of reality and virtuality, including AR in which the real world is augmented by virtual enhancements and AV (augmented virtuality) in which the virtual world is augmented by the real (Milgram et al. 1995, 282–92).[8] The more obviously artificial nature of AR/VR visualizations may be used in a classroom setting to illustrate the sorts of choices that historians make in any evaluation/representation of historical data. What becomes important is not the degree of artificiality but rather the transparency of the method. Just as the creator of the virtual representation must make choices about how “real” to make their visualization (what to include and exclude), so the historian makes choices regarding what data to include and how that data is represented. The artificiality of extended reality technologies thus opens the door to conversations about not only the material being studied, but also the means by which it is studied.

The appeal of VR and AR is not new. Humanity has long held a fascination for trying to create a virtual experience of reality. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, panoramic paintings became particularly popular, including the development of 360º murals that were intended to fill the entire field of vision and make the viewer feel as if he or she were in the virtual world depicted by the paintings (Thompson 2015).[9] The nineteenth century also saw the development of the stereoscopic[10] viewer and images, precursors to the View-Master and, more recently, Google Cardboard (Virtual Reality Society 2016). Experimentation in film also contributed to the development of the technology, particularly the widescreen camera lens. French filmmaker Abel Gance introduced “polyvision,” a specialized widescreen film format that involved the simultaneous projection of three reels of film in a lateral montage, in his 1927 silent epic Napoléon (Cuff 2015, 24). Polyvision, as well as the later development of CinemaScope and Panavision using widescreen lenses, gave the audience a panoramic and, subsequently, more immersive film experience. It was not until 1929 and the development of the flight simulator (Virtual Reality Society 2016) that a virtual environment was designed for teaching rather than for entertainment purposes. This focus on the pedagogical potential of virtual environments has become even more important today as VR and AR evolve from game platforms to teaching tools.

Both technologies exemplify the concerns faced by experts building virtual heritage sites.[11] For historians, archaeologists, and other scholars, the photorealism of the 3D models is the primary goal. In general, there are ten principles of 3D photorealism: clutter and chaos; personality and expectations; believability; surface texture; specularity; aging dirt, rust, and rot; flaws, tears, and cracks; rounded edges; object material depth; and radiosity (light reflections off diffused surfaces) (Fleming 1998, 3). To achieve photorealism, the computer-generated object should demonstrate at least seven of these ten principles (Fleming 1998, 3–4). The virtual world should not be pristine and unblemished because reality is messy and dirty. This concern for photorealism does not, however, apply in the same way to human 3D models. In fact, few virtual heritage reconstructions include human figures and for good reason. Firstly, creating realistic human models is time consuming and expensive since it requires a digital artist with considerable skill in drawing and modelling figures from life. Architectural and cultural artifacts are usually less difficult to build as 3D models. Secondly, living models, unlike objects, are expected to move in some way. Animation adds a complex layer of technology that is usually not the primary focus of the recreated physical environment. Thirdly, and most importantly from a pedagogical point of view, human 3D models can complicate the virtual experience by encouraging the user to try and interact with them rather than focus on the physical reconstruction of the heritage site. Finally, there is the consideration of how exactly “real” such human figures should be. The more realistic the 3D model of the living figure, the more likely that it will become an example of the uncanny valley phenomenon described in social robotics: that is, the 3D model will be almost too real so that the minor imperfections of the recreation become disturbing and even repulsive.[12] Thus a caricature of a human figure may be more appealing and effective than a truly realistic and complex representation in VR or AR.

Two Historic Recreations: Modelling Challenges

Bologna 3D Open Repository is the result of a collaborative project between the municipality of the city of Bologna and CINECA Interuniversity Consortium, an academic supercomputing group that offers technological support to education, business, and the community. The project’s primary goal was to build 3D models for the creation of a virtual Bologna that the municipality could use to promote the candidacy of the city’s historic porticoes, or arcades, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The repository is now maintained as a site dedicated to the collection and sharing of the 3D models for didactic purposes—namely teaching students about the city and its history. Figures 1 through 3 show some of the 3D models created by the consortium:

Through these visualizations, students can learn about the architectural history of Bologna from the medieval period through to the 18th century. The computer graphics are high quality and demonstrate a number of the principles of digital photorealism. In particular, the architecture and landscapes exhibit great attention to detail and authenticity. The project includes human figures, not typical of most historic recreations, and these figures are generally caricatures rather than realistic representations of people. Certainly, such a use of humor in a virtual historic re-creation emphasizes the project’s desire to appeal to a broad, public audience (Guidazzoli, Liguori, and Felicori 2013, 58–65).[13] And the less-than-realistic style of the human figures avoids the potential issue of the uncanny valley.

Like the Bologna 3D Open Repository, the 3D Paris Saga project uses AR and VR to tell the narrative of the architectural history of Paris. Their approach, however, differed considerably. Dassault Systèmes, a European software company that specializes in 3D design, built a complex virtual world that traces the history of the city through almost 2,000 years with a special focus on a 3D reconstruction and interactive experience of the fourteenth-century Palais de la Cité and the Sainte-Chapelle (“Voici” 2015). The project originally included a 90-minute television documentary, a CAVE experience of the virtual world using 3D glasses (Vitaliev 2013), a PC-compatible interactive 3D website, and an AR-enhanced print book (Dassault Systèmes 2012). The visual accuracy and detail of the 3D architecture, topography, and atmosphere enrich the photorealism of the virtual world (see Figure 4). The fact that familiar monuments are shown in various stages of construction transforms the virtual experience into a deeper educational one. Considerable attention is also given to the appearance of the skies, reflecting typical Parisian weather rather than an idealized and eternal perfect sunny day (see Figure 5). Again, 3D human models that inhabit the virtual city are not a common feature of such historic recreations. They are merely shadowy figures and remind the viewer that Paris was always inhabited; however, because the figures are so ethereal, they avoid the uncanny valley phenomenon and encourage the viewer to explore the historic constructions rather than try to interact with the animated models themselves.

Figure 4. View of the Grande Cour and Trésor de Chartres with shadowed human figures in the courtyard (Dassault Systèmes).

Despite its initial success, the VR element of the project is no longer easily accessible: the CAVE environment is only available at Dassault’s Paris headquarters by appointment to select visitors.

Virtual reconstructions such as these help students understand cultures, histories, and artifacts that are physically, temporally, or culturally distant. While it may be difficult for American students to visit Notre Dame, extended realities can help them experience it in a way that more traditional media cannot.[14]

The AR-Enhanced Text

The most successful component of the 3D Paris Saga has been the AR-enhanced companion print book published by Flammarion. Whereas current AR technology uses a mobile application on a smart device to trigger the digital enhancements embedded in the printed page, Dassault requires the user to hold select pages from the print volume up to the web camera on a PC.[15] Like a virtual pop-up book, the 3D models appear on the page as viewed through the computer screen (see Figure 6).

The user may turn the book in order to see all sides of the 3D model, thereby gaining a greater appreciation of Parisian architecture throughout history, including the Middle Ages. However, interacting with the book and the technology is awkward and lacks the mobility that a smart device offers. It is also counterintuitive to the standard reading process since the user holds the book but looks away from it at the computer screen.

AR-enhanced texts are not new. Mark Billinghurst and his team at HitlabNZ (the Human Interface Technology Lab at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand) created some of the first examples in the early 2000s. Called “MagicBooks,” the texts are designed to encourage children to read:

The computer interface has become invisible and the user can interact with graphical content as easily as reading a book. This is because the MagicBook interface metaphors are consistent with the form of the physical objects used. Turning a book page to change virtual scenes is as natural as rotating the page to see a different side of the virtual models. Holding up the AR display to the face to see an enhanced view is similar to using reading glasses or a magnifying lens. Rather than using a mouse and keyboard based interface users manipulate virtual models using real physical objects and natural motions. Although the graphical content is not real, it looks and behaves like a real object, increasing ease of use. (Billinghurst, Kato, and Poupyrev 2001, 747)

Although early forms of AR used abstract, specifically designed images (often QR codes) to trigger enhancements, the technology has advanced to the point that any complex, informationally dense image may serve as a fiducial marker. The use of mobile apps and smart devices makes interaction with the text easy and intuitive.

A new wave of AR technology seems to be driven by the increased capability and ubiquity of our mobile devices. Jordan Frith notes that early theories about the internet hypothesized that humanity (or at least that bit of it that could afford computers) would become more isolated and private—living their lives at home—we assume spending their time (and money) ordering from Amazon (Frith 2002, 136). Mobile computing has diverted us from this possible future. Instead, we are bringing our private lives into public spaces, attempting to control these spaces through our AirPods or earbuds, our Google maps, and Four Square—all the while curating our experience of the urban environment on social media.

It is to this mobile landscape that AR brings such promise. AR’s ability to overlay the physical world with digital information offers a new kind of experience and understanding of our world. Victoria Szabo argues that AR may be used to make the site of cultural history more meaningful to their visitors through the layering of digital information over the physical space. As she explains, “Mobile AR systems have the potential to help users create situated knowledge by bringing scholarly interpretation and archival resources in dialog with the lived experience of a space or object” (Szabo 2018, 373). In so doing, she argues, the visitors move from comprehension of the site which entails historical distance and critical interpretation—in other words traditional educational materials that might guide visitors through the site—to apprehension. Apprehension is more experiential learning and “relies on the tangible and felt qualities of the immediate experiences” (Martin 2017, 837; quoted in Szabo 2018, 374). The ability of AR to merge the “real” physical world of the historical site with digital material such as reconstructions, interpretive data, etc. facilitates both apprehension and comprehension.

When we consider an AR publication, however, we are moving away from Szabo’s paradigm to its inverse. With the book form, we are beginning not with the physical space—which already brings with it the tangible learning central to apprehension—but with the more traditional way of making meaning within education: the book. AR is still in its infancy in the publishing industry, but interest in its possibilities is growing. According to one 2017 poll, only 9% of Americans have experienced an AR application (Martin 2017, 20). Yet in this same year, five major tech companies, including Apple, launched AR frameworks or apps following the surprising success of the AR game Pokémon Go in 2016 (Tan 2018, 22). According to Digital Capital, an investment group, AR and VR are poised to become major players in technology. They estimate an AR/VR market of $108 billion with AR as the primary force and with predicted revenues of $90 billion by 2022 (Tan 2018, 22). This market data may seem irrelevant to academia, but what it means is that publishers are beginning to move into AR as well, creating new opportunities for academic AR publications. Major news media such as The New York Times, The Guardian, The Wall Street Journal, BBC, CNN, Hulu, and Huffington Post have all experimented with some form of Virtual, Augmented, or Mixed Reality (VAMR) media (Martin 2017, 21). Deniz Ergurel, technology journalist and founder of the media start-up Haptical, asserts that VAMR marks the next major technological shift. According to Ergurel, “Every 10–15 years, the technology landscape is reshaped by a major new cycle. In 1980s, it was the PC. In 1994, it was the Internet. And in 2007, it was the smartphone. By 2020, the next big computing platform will be virtual reality” (Martin 2017, 20).

AR text, because it is multisensory, can bring some of the features of experiential learning to its readers including the visual features of the text, historical contextualization, images, audio, video, data visualizations, supplementary text, and most importantly, 3D AR augmentations. The multimodal possibilities of AR texts make them particularly useful to teachers of literature that is culturally or historically distant because, through such reading environments, students may be more easily introduced to the material culture that surrounds and creates the texts they are studying. Furthermore, this approach allows the students to engage with the material in a multimodal fashion, appealing not only to the language centers of the brain, but to the visual and aural centers as well. The digital environment encourages the reader (and even the author) to “play” with the text in terms of design and interactive engagement (Douglas 2000, 65). The brain’s ability to play is something we, like many animals, are hardwired to do for survival; consequently, the process of reading text, especially digital text, has neurological value precisely because it encourages the brain’s playfulness (Armstrong 2013, 26–53).

Conclusion: The Future of VR and AR

The argument can be made that neither VR nor AR offers a truly immersive experience because not all five primary senses of the participant are engaged. Certainly, computer technology can generate both visual and aural enhancements in the form of 3D models and recorded sound. However, touch, smell, and taste are more challenging. Haptic tools, such as gloves or a stylus device, are becoming more popular and offer both the VR and AR user the ability to touch and sense physical contact with virtual objects. AR actually has the advantage of offering much more real-world haptic information by default than VR can. With AR, the user can feel the actual book because it can be a real-world object, but, in VR, the technology must do something to allow the participant to feel such an object because the entire environment is computer created. Demand has been less so far for smell and taste, although there have been some experiments, largely unsuccessful, in adding odors to virtual worlds. Recent developments in the creation of technological tools to trigger the sensation of taste in an individual, such as the “digital lollipop” (Ramasinghe and Do 2016) and Electronic Food Texture System (Niijima and Ogawa 2016, 48–9), show promise for the eventual incorporation of this primary sense into the VR experience.

If full sensory engagement is required for a virtual world to be completely realized, then perhaps the most immersive and interactive experience of the Middle Ages may be one that is not computer-generated at all: Jorvik Viking Centre. Located in York, England, the museum and tourist attraction was created in 1984 and has long been famous for its appeal to the senses of its visitors, most significantly the sense of smell. A quick glance at such online review sites as Trip Advisor, Virtualtourist.com, etc. makes it clear that the intentional smells associated with the exhibit are not just memorable but also a significant factor in recommending the Jorvik Viking Centre. The exhibit’s use of scents to enhance the Viking experience has even generated scholarship exploring the effectiveness of odor in retrieving the memory of the tourist experience. Apparently, it is very effective (Aggleton and Waskett 1999, 1–7).[16] The Centre, in fact, intentionally engages all the senses of its visitors in order to make the historic re-creation a memorable and educational experience. In 2015, it actively promoted its non-digital exhibit in the language of virtual and augmented technologies, inviting guests to have a 4D Viking encounter rather than a mere 3D one. In this campaign, the Centre emphasized that all five primary senses of its visitors will be fully engaged (Jorkvik Viking Centre 2015):

- “Touch: Handling collection of Viking Age artefacts, including bone, antler and pottery, on offer to visitors in the queue—participants will be blindfolded and asked to identify the object/material.”

- “Sight: Binoculars are available in the ‘Time Capsules’ that take visitors around the recreated Viking city. These are to be used to spot the various animals that inhabit the scenes of the ride experience. A ‘spotter’s guide’ will be issued, allowing visitors to score themselves against their finds.”

- “Taste: A Viking Host will be on hand to explain the Viking diet and offer up tasters of unsalted, dried cod (a Norse delicacy) and for visitors over 18, Mead, a beverage made of fermented honey, will be available.”

- “Smell: JORVIK is already famed for its re-creation of the smells of the 10th century York but this will be taken a step further with the introduction of ‘smell boxes’ in the ‘Artefacts Alive’ gallery. A new aroma will be located next to a display of object, with the smell paired to match the contents. [Four] smells will be available: Iron (for the Iron working display), Leather (next to the leather and shoemaking), Beef (for the general living display), and wood (for our wood finds).”

- “Sound: A Viking will entertain visitors with period-specific musical instruments (including a recreation of the panpipes found at Coppergate) and retellings of some favourite Viking sagas.”

But as entertaining as the Jorvik Viking Centre clearly is, do we really want, or even need, a fully immersive and interactive experience? From the perspective of pedagogical effectiveness and student engagement, perhaps not. AR may, in fact, be the technology that has greater potential as a pedagogical tool precisely because it allows the user to learn in a digital environment while always keeping a strong foothold in the physical world—a reminder that the 3D world is not, ultimately, a real place.