Introduction

Wikipedia is an open access, online resource built on the creative and administrative contributions of thousands of individuals around the world. With more than 35 million articles in 280 languages, Wikipedia is a ubiquitous presence in popular culture and the classroom alike. An immediately familiar resource for students (and often the place where they begin their research), Wikipedia is increasingly recognized as an essential component of the research process, “an essential tool for getting our digital collections out to our users at the point of their information need” (Lally and Dunford 2007; cf. Head and Eisenberg 2010). The openness of the platform to anyone interested in contributing, however, has exposed some biases and deficiencies in the encyclopedia’s coverage and editing community. Wikipedia has a major gender imbalance in contributing editors—women are estimated to make up 9 to 13 percent of them (Wadewitz 2013; Bayer 2015)—and the editing community has largely minimized women’s history, with an estimated 15.5 to 17 percent of the biographical articles focusing on women (Proffitt 2018; Moravec 2018).

Feminist activists and scholars have developed a set of approaches to address the Wikipedia gender gap. In 2012, undergraduate student Emily Temple-Wood founded the WikiProject Women Scientists, which sought to ensure “the quality and coverage of biographies of women scientists.” Alongside Rosie Stephenson-Goodknight, she co-founded WikiProject Women in Red. On Wikipedia, red links mean that “the linked-to page does not exist.” The Women in Red project continues to create lists of links that are either about “a woman, or a work created by a woman.” These efforts garnered Temple-Wood and Stephenson-Goodknight the first co-awarded Wikipedian of the Year award. Aaron Halfaker (2017) notes how Temple-Wood’s efforts not only improved the quantity of content related to women on Wikipedia, but also the quality of entries.

Collective gatherings have shown promise for supporting new editors, as groups like Art+Feminism, AfroCROWD, Fembot, and FemTechNet have taken a “do-it-yourself and do-it-with-others” approach. Wiki edit-a-thons hosted by such groups take place in public spaces like coffee shops and museums, and at libraries ranging from New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture to Connecticut College’s Shain Library, the site of this study (Boboltz 2017). Librarians have taken on a key role in facilitating the work of groups seeking to add content about marginalized people and issues to Wikipedia. They have sought out ways to not only support activists doing this work, but also to institutionalize engagement with Wikipedia. For example, at West Virginia University, academic librarians worked to enable students to receive required service credit hours for editing Wikipedia, drawing sorority groups and graduate students into this work (Doyle 2018, 63). Finally, as evidenced by the work of Wiki Education, classes are increasingly bringing together student learning with editing Wikipedia: in the Fall 2018 session, 321 classes participated across a wide range of academic fields.

Over three iterations, a feminist theory class and the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives at Connecticut College collaborated on an in-depth Wikipedia archival research assignment (Appendix 1) with a twofold goal: first, to address some of these Wikipedia deficiencies by creating and editing articles through a feminist scholarship lens, and second, to engage students in the process of knowledge creation for a public audience (Appendix 2). This project built upon an ongoing collaboration between faculty and archivists to develop project-based learning opportunities in institutional collections, and reflects a growing recognition of Wikipedia’s potential for generating “meaningful service learning experience[s]” for students (Davis 2018, 87). The first iteration of the course allowed students to develop topics that were far ranging, but this initial approach resulted in some issues with their engagement with Wikipedia (e.g. overly specific topics or concepts that were difficult to document). The second and third iterations of this course focused on identifying gaps in Wikipedia that could be directly tied to the Lear Center’s collections. The team reviewed course learning goals and developed a list of relevant material in the Lear Center (Appendix 3) which connected to themes in feminist theory such as women’s leadership, ecofeminism, poverty, and racial and disability justice. Students conducted research using these collections and worked to either generate or modify existing Wikipedia content. Students then summarized their experience in public presentations at the end of the semester. The resulting project represents a collaborative approach between students, faculty, and archivists, and showcases the community of shared interests and values that are fundamental to the digital humanities (Scheinfeldt 2010). This paper argues for the power and potential of this type of collaboration in developing projects that challenge students to engage in practical feminist praxis and to make connections between theory, archives, and public digital engagement.

Digital engagement with Wikipedia offers a unique set of openings into feminist theory and history for undergraduate students. Wikipedia serves as an accessible platform for students to consider questions of evidence, representation, and knowledge creation. While many use Wikipedia as the first stop for information, few understand how this information is created. The project team recognized that the platform’s ubiquity and familiarity could serve a dual purpose: first, to emphasize the importance of contributing reliable, accurate information to a site used by so many, and second, to help mitigate potential nervousness about working with digital technology in the public realm. This pedagogical approach ensures that students understand the historical and political context of Wikipedia and its community. They can draw upon their experience with this platform to ask questions and actively engage with media.

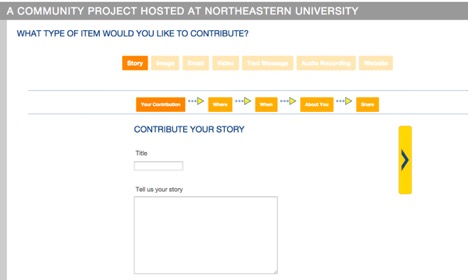

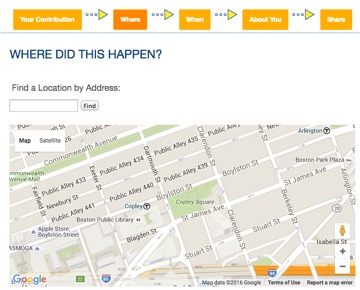

The team partnered with the Wiki Education Foundation (Wiki Ed), a non-profit entity separate from Wikipedia that supports faculty who incorporate Wikipedia into their curriculum. The program emphasizes that students “gain key 21st century skills like media literacy, writing and research development, and critical thinking, while content gaps on Wikipedia get filled thanks to [their] efforts” (Wiki Education, n.d.). Wiki Ed provides tools and resources, including interactive tutorials about the tenets of Wikipedia and basics of editing and adding content. The Wiki Ed Dashboard serves as the digital home for the class, enabling faculty to create and manage their Wikipedia assignment and to monitor student progress. For students, it contains the tutorials and relevant information for the Wikipedia assignment and allows them to track the progress on their article as well as that of their classmates. Faculty and archives staff use the dashboard to design and monitor students’ work in real time.

A key aim of the project was that students experience the process of conducting and presenting research. Much of feminist theory is based in intensive critique of research and representational practices. Students risk becoming either highly critical of all scholarship without engaging the merits of the work or fearful of creating their own work, believing that it will also be easily criticized. In this assignment, students learned to balance rigorous critique with a strong understanding of knowledge production. Editing content for a general audience on Wikipedia raised the stakes for students: the challenge of writing for the public proved more rewarding than the perceived standard of writing for only the instructor (Davis 2018, 88). The team presented Wikipedia’s overlapping gender and racial imbalance as a problem that students had the power to address as part of a broader scholar-activist community. Student feedback about the challenge and meaning of the assignment supports scholars’ arguments that structured opportunities for student interaction with institutional special collections and archives generate deeper engagement with and investment in research and its meaning (Tally and Goldenberg 2005).

Institutional Context

Connecticut College is a private, undergraduate liberal arts institution in New London, Connecticut. It offers 56 majors, minors, and certificates to approximately 1850 undergraduates. As with many liberal arts colleges, Conn’s culture is deeply rooted in teaching and learning. These efforts are supported by several campus resources and partnerships, including the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Technology Fellows Program, as well as by collaborations between faculty and staff in the six academic centers across campus, the campus’ Charles E. Shain Library, and the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections and Archives. The Lear Center is home to Connecticut College’s collections of rare books, manuscripts, and archives. The Center works extensively with faculty to develop projects which engage students in active primary source research, both in the classroom and increasingly as a part of the College’s emerging Digital Scholarship program. The Digital Scholarship program provides technological, project, and platform support for student, staff, and faculty digital projects with a focus on the pedagogical, classroom-based side of digital scholarship. The Lear Center has been involved with the College’s Digital Scholarship efforts from the start, as it sees digital scholarship as a natural extension of outreach and use activities. By combining primary source research with digital methodologies, the Lear Center offers students a unique opportunity to become active producers of knowledge, rather than passive consumers, and to convey this knowledge to a real-world audience.

Wikipedia as a Space for Feminist Praxis and Skill-Building

Gender, Sexuality, and Intersectionality Studies (GSIS) emphasizes feminist praxis, the “philosophy and practice of participatory democracy and situated knowledges” (Naples and Dobson 2001, 117). At its heart, feminist praxis is a call for hands-on engagement with core questions within the field, particularly in how each person can participate in the creation, circulation, and usage of knowledge. While feminist theory can be taught in a manner that solely focuses on theories of gender, sexuality, and other categories of analysis, the course provides an opportunity to enact a praxis-based pedagogical strategy. This approach can deepen students’ understanding of theory, asking them to apply theory to their work and consider its accuracy or limitations when put into practice.

Feminist theory presents a challenge to undergraduate students who are drawn into GSIS through varying avenues. As feminist theory is interdisciplinary, students encounter authors that may be writing from fields or on topics they have yet to study. They also may not have developed necessary reading skills or frustration tolerance (that is, the ability to navigate work that is dense, references unfamiliar ideas and academic jargon, or challenges their perspective). Scholar Gloria Anzaldúa (1991, 252) argues that “[t]heory serves those that create it” and that as a queer woman of color, she had to challenge existing theories to adequately account for her knowledge and experiences. Indeed, students may struggle to see themselves or their concerns in texts that are written in a language and for an audience far removed from themselves, or in the disproportionate amount of scholarship written by white Western cisgender women. However, Anzaldúa also reminds us that works have “doors and windows,” or entradas (1991, 257). As readers come with a need to find themselves in texts, having multiple entradas through diverse course readings and assignments creates a range of opportunities to engage with and find connections to feminist theory. It is imperative for instructors to find ways to address these concerns while ensuring that students directly work with the scholarship that undergirds the field and its contributions more broadly.

The Advanced Readings in Feminist Theory course is a required annual offering for both GSIS majors and minors (see Appendix 4 for the 2017 syllabus). This 300-level class is for some students their first undergraduate course that heavily centers theoretical work. This course draws students from a range of disciplines including English, Music, East Asian Studies, and Psychology. In the 2017 version, McCann’s and Kim’s edited collection, Feminist Theory Reader (2016), and Moraga’s and Anzaldúa’s edited collection, This Bridge Called My Back (2015), served as the core texts, along with additional readings. Key themes included theorizations of inequality, violence, and intersectional feminism along with epistemological frameworks such as standpoint theory and feminist phenomenology. The learning goals for the semester sought to ensure that students would be able to:

- Knowledgeably discuss key forms of feminist theory in terms of their content and implications

- Articulate the significance of feminist theories to their own research and education

- Effectively present their research to a public audience online and in person

It was important to devise course assignments that asked students to put into practice the frameworks they were using so that they could more critically understand the stakes of feminist theory, articulate key ideas in their own words, and apply these concepts to unique projects.

The platform of Wikipedia offered a novel means to take feminist theory out of the ivory tower and illuminate the value of the course content for students. Positioned as editors, students were challenged to make meaning out of theory and archival materials for a broad audience. Working with Wikipedia made coursework relevant by making it accessible to a public at large, thus enabling to students to find a compelling reason to stay engaged throughout.

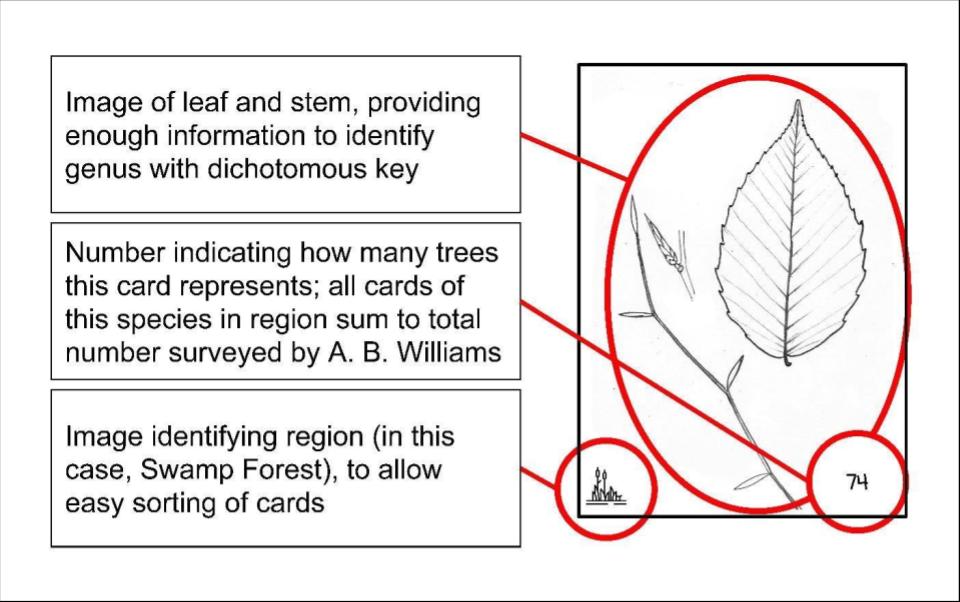

Collaboration in the Archives, Navigating Wikipedia’s Norms

Coupling the Wikipedia platform with archival research provided a set of connections and resources to facilitate the achievement of these pedagogical aims (see the Fall 2017 course dashboard). Faculty and archives staff reviewed course learning goals and core themes and identified relevant, robust topics in the collection that either had underdeveloped pages or were absent from Wikipedia. Collections were assessed to ensure each had sufficient primary and secondary material to build an entry that would meet Wikipedia’s standards. Students used primary source material such as photographs, correspondence, and reports, while drawing upon secondary sources to verify their claims and authenticate their subject’s notability, a critical standard of Wikipedia.

The practice element of feminist praxis requires skill building and serves to reinforce the content of feminist scholarship. As students worked with Wikipedia, they practiced what feminist theorist Donna Haraway describes as learning the ins and outs of knowledge production and representation. She argues that “understanding how these visual systems work, technically, socially, and physically, ought to be a way of embodying feminist objectivity” (Haraway 1988, 583). Through the process of conducting research in the archives and in secondary sources, drafting and revising content for Wikipedia, and then presenting and reflecting on this work, students were challenged to consider multiple facets of knowledge production. Moreover, they encountered those questions and challenges at the heart of feminist debates about epistemology, as they considered the perspectives included in the archival source material, their own positionality in relation to their research, and the dynamics that exist within Wikipedia vis-à-vis its standards and editing community.

Wikipedia’s policies and practices hold both potential and barriers for its usage in a feminist classroom. The formal policies are expressed most directly through the Five Pillars that address the basics of Wikipedia. While the first and third pillars state basic elements of Wikipedia (it is an encyclopedia; free content that is edited), the second, fourth, and fifth pillars present elements of Wikipedian culture. Pillar two, “Wikipedia is written from a neutral point of view,” contains the key conflicts that are perennially navigated in our feminist theory assignment and have been challenged by feminist scholars (Gauthier and Sawchuk 2017). It states:

We strive for articles in an impartial tone that document and explain major points of view, giving due weight with respect to their prominence. We avoid advocacy, and we characterize information and issues rather than debate them. In some areas there may be just one well-recognized point of view; in others, we describe multiple points of view, presenting each accurately and in context rather than as “the truth” or “the best view.” All articles must strive for verifiable accuracy, citing reliable, authoritative sources, especially when the topic is controversial or is on living persons. Editors’ personal experiences, interpretations, or opinions do not belong. (Wikipedia 2018)

In response to standpoint and situated knowledge theories, it is de rigueur in feminist theory to recognize and acknowledge one’s relationship to a topic (Collins 1986; Haraway 1988; Harding 1992). While feminist scholars range in their approach to academic tone, there is generally an acceptance of taking stances that explicitly embrace values such as antiracism and antisexism, rather than avoiding any direct acknowledgment of their interest in a subject and the stakes of inquiry (hooks 1998; Mohanty 2003). The encyclopedia form of Wikipedia thus at once provides an opportunity to build a broader audience for feminist-themed topics while disavowing the motivation that drives feminist engagement with the platform.

A critical analysis of power and the circulation of knowledge also conflicts with the assertion in the second pillar that as members of Wikipedia, “We strive for articles that document and explain major points of view, giving due weight with respect to their prominence in an impartial tone.” Michelle Moravec’s essay “The Endless Night of Wikipedia’s Notable Woman Problem” provides insight from the field of women’s history about why assumptions about prominence continue to stymie the work of feminist Wikipedians. She argues that it is important to:

consider the difference between notability and notoriety from a historical perspective. One might be well known while remaining relatively unimportant from a historical perspective. Such distinctions are collapsed in Wikipedia, assuming that a body of writing about a historical subject stands as prima facie evidence of notability. (Moravec 2018)

The presumption of prominence fails to address the ebb and flow of cultural memory, and in practice requires that women rise to a level of exceptionality to register as worthy of inclusion in Wikipedia. Moravec cites the reality that the “‘List of Pornographic Actresses’ on Wikipedia is lengthier and more actively edited than the ‘List of Female Poets.’” While arguably both lists could serve as useful sources of information, this gap highlights an editorial priority based on editors’ personal consumption practices rather than the quantity or quality of an artist’s contributions. Wikipedia itself has articles addressing the challenges of notability, and includes discussions of the two camps, deletionists and inclusionists, who struggle over either stringent adherence to the requirement or the allowance of entries that are viewed as “harmless.” The ongoing struggle over how to best balance the intention of Wikipedia to serve as a reliable source of information with the demand for increasing inclusion of diverse content, and editors who echo broader debates within feminist scholarship and our society at large, is critical for students to take on in their learning.

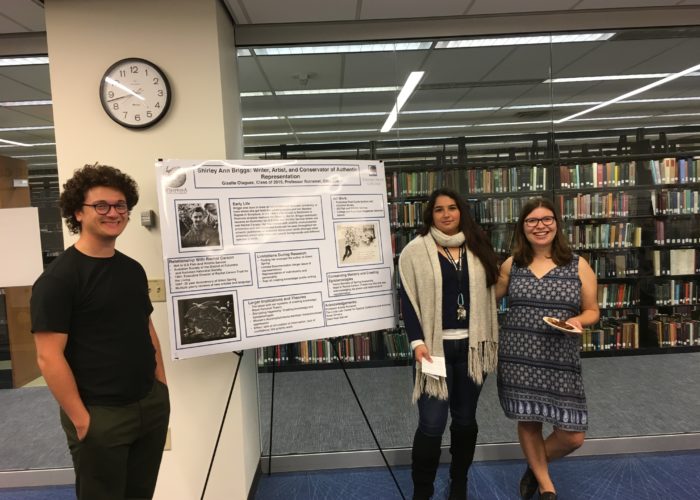

Figure 1. A student created a new Wikipedia entry for Eli Coppola, a poet whose work addresses disability and sexuality.

Assessment and Outcome

The project’s aims—archives staff’s desire to develop extended, class-based community engagement with library resources and collections, and the faculty member’s desire for students to participate in the collaborative process of planning, conducting, and presenting their research to a public audience—were met. The project’s design allowed students to demonstrate their learning through multiple formats (archival research, work with Wikipedia, a poster presentation, and a reflection essay), as well as to provide feedback through the reflection essay, in-class discussions, and the anonymous, end-of-semester teaching evaluation. While students at times struggled with the assignment, the project team determined that they not only gained skills related to feminist theory, metaliteracy, and critical reading, but recognized the long-term value of their work for their future careers.

Students presented their work publicly in the college library through poster presentations. Along with a final reflection essay, these components served to assist students in recognizing the level of effort that they put into this project and its significance to their understanding of feminist theory. Students’ projects were assessed on their work in the archives, the Wiki dashboard, effort and collaboration with classmates, and their poster presentation and reflection essay (Appendix 5, Appendix 6). This assessment approach emphasized students’ engagement and centered the need to connect their work with archival material and Wikipedia with course readings. The assignment set a clear expectation that students engage in feminist praxis, considering how the work they were doing in researching and creating public-facing content was informed by feminist theory and vice versa.

Course outcomes

Students’ reflection essays[1] provide insight into how they understood the work they did throughout the project and what doors opened for them. They were asked to make a unique argument about the assignment in terms of feminist theory and a core facet of the project. Students highlighted their priorities, including gaining a deeper understanding of key questions in the course content, challenging the limitations of Wikipedia, and preparing for post-graduate life. One student made explicit how the assignment addressed theoretical questions within the field:

Similar to how feminist epistemology seeks to change, redefine, and rewrite mainstream theories which exclude women’s narratives … metaliteracy “challenges traditional skills-based approaches to information literacy” [Mackey and Jacobson 2011, 62].

By putting questions of epistemology into conversation with metaliteracy, the student emphasized the ways that the assignment helped students think and act critically in their project work.

Two students’ responses to engaging with Wikipedia demonstrate the struggles they encountered and their differing attitudes to the project’s outcomes. The first student’s response centered on the importance of working in the archives. They wrote, “Through the use of primary documents and news clippings found in the archives, I was able to navigate the problematic limitations that Wikipedia exhibits.” They found that the collections provided the necessary content to ensure that they were showing notability and to avoid challenges raised by Wiki editors.

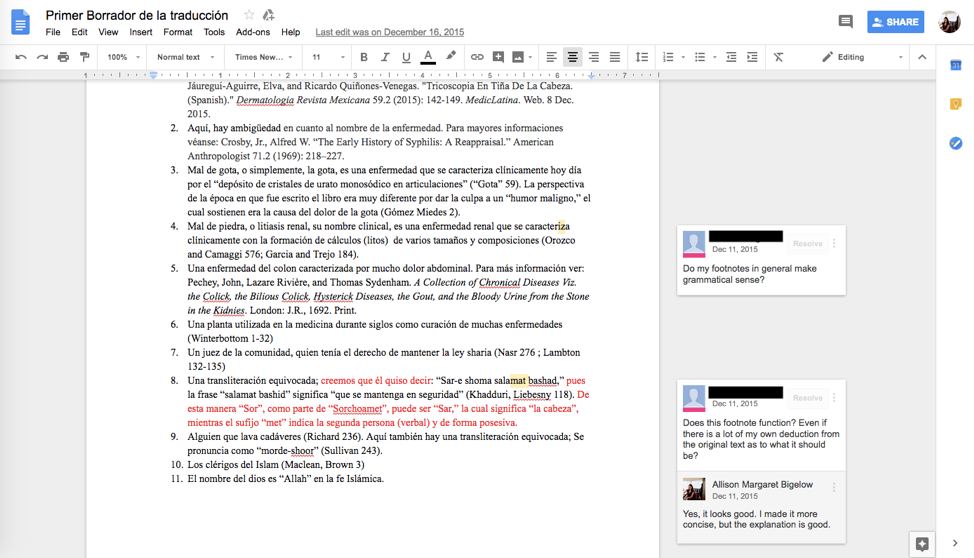

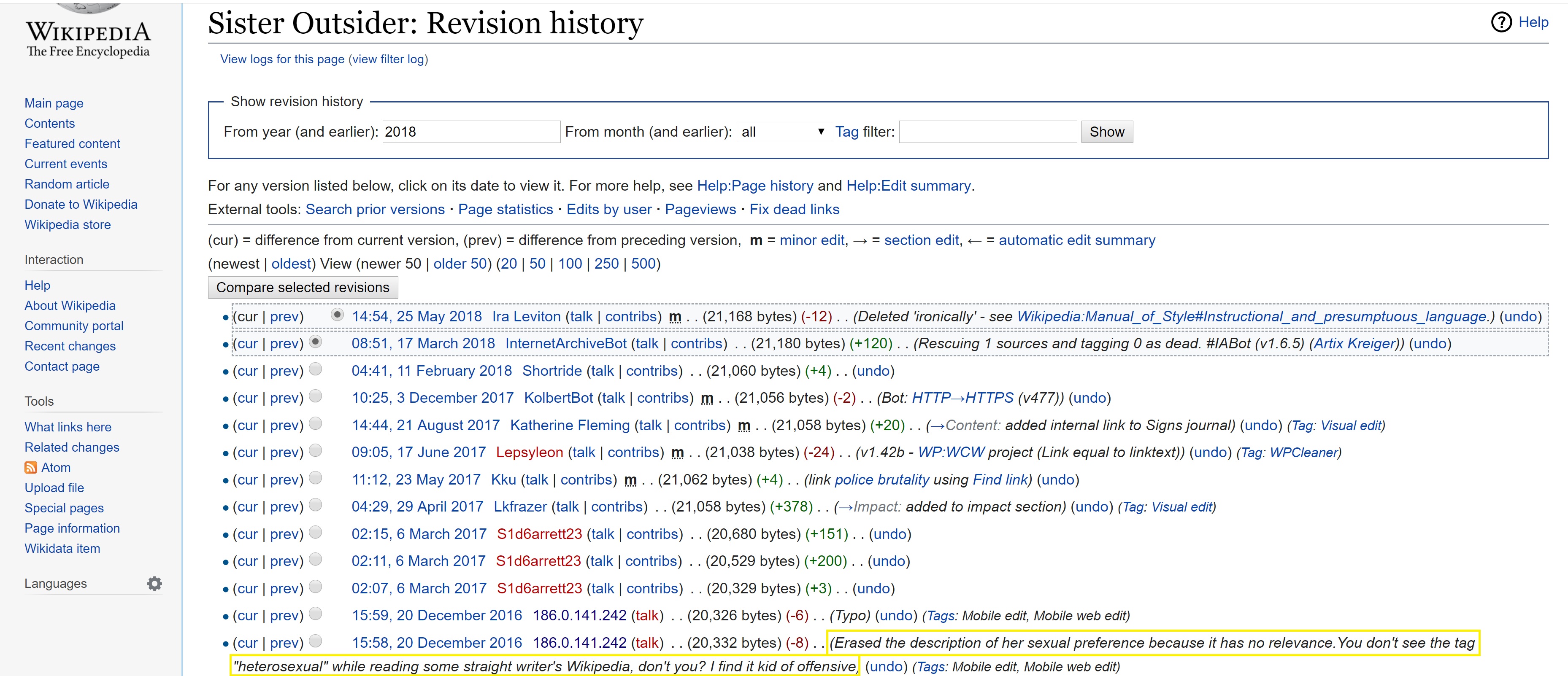

Figure 2. A Wiki editor claimed that naming Audre Lorde’s “sexual preference” was offensive. Lorde was a famously self-described “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” who emphasized the importance of naming herself in her writing. This editing challenge suggests a bias against public identification of LGBTQ people.

In contrast, another student was frustrated by the constraints of Wikipedia. They argued that due to Wikipedia’s neutrality standards “feminist knowledge is neither present in its full unapologetic extent, nor is it accessible to the global web users.” The student recognized the potential of Wikipedia to reach many people and was thus frustrated that the process of composing work for Wikipedia required both a tone and selection of content that did not align with either the student’s understanding of feminist knowledge or course readings that were unapologetically explicit in their political aims. While this response may be viewed as a negative outcome, it showed students’ conscious engagement with a critical question about how feminist knowledge circulates and is constrained, as well as a deeper understanding of how Wikipedia operates.

A final example of student reflection essay suggests why collaboration is key to the assignment. They observed that:

collaborating with the Wiki Education Foundation and the Linda Lear Center gave me confidence… as well as built upon my skills… being able to see the results of our work on such a public and well-known domain, shows that our work as students is valued and relevant to scholarship; we don’t have to wait to enter the professional realm to have our work recognized.

In this case, the student recognized how they were supported by archives and Wiki Ed staff as they worked toward creating a public-facing article. The student identified this assignment as opening a door into a public realm that they had previously assumed would only become available after graduation. Teaching evaluations showed that students thought about the value of the assignment. One student emphasized the role that writing for Wikipedia had in their investment in the project, noting:

The work I did on Wikipedia will be looked at by hundreds of people even after the project is done, instead of just a paper that will only be read by my professor… I was surprised [by] how much it exposed me to new and constructive ways of research.

The student found that knowing that their work would be read by a wide audience rather than simply by a professor for evaluative purposes was motivating. Moreover, the assignment introduced archival research and pushed them to delve into how what they were exploring in the archives could be put into conversation with other sources. For another student, “The Wikipedia project was difficult but it was one of the most important projects I have ever done for a class.” This student echoed a sense among many students that the assignment was higher in difficulty because of the effort required to collect, analyze, and create multiple representations of their findings. By the end of the semester, students recognized the value of learning how to create and share information with an audience beyond the walls of their institution.

Sharing this project with a broader Digital Humanities community through blog posts and conferences produced further positive outcomes. For example, Alex Ketchum, feminist food scholar, tweeted that the description of this digital project at the Women’s History in the Digital World conference in part inspired her own digital project (Ketchum 2018). Each project adds to the network of possibilities, inviting conversations and collaborations that move ideas forward and create a rich community experience.

Archives outcomes

The use of Wikipedia to develop an online presence for underrepresented archival collections offered a meaningful opportunity to generate greater access and exposure to these collections, as well as to create a valuable public-facing resource. Working with faculty and students provided an opportunity to examine collections through a feminist lens, bringing to a global audience the lives and histories of women with little public representation. Through multiple sections of the class, twenty-six entries were created on the work of women whose contributions ranged from environmental and labor activism to civic and institutional leadership. Each entry cites the Lear Center’s collections, increasing exposure of its archives and encouraging engagement on a global scale (Appendix 2).

Staff contribution at each stage of the project emphasized the power and potential of collaboration. Archives staff worked with faculty to develop course outcomes and select appropriate collections, and provided an important support system for students throughout the project. Staff engaged students in the work of primary source research, helping them think through ways of structuring their entries, find additional sources, and cite material appropriately. The intensive one-on-one work opened important avenues for conversations about the complexities of archives and archival research, the ethical issues surrounding privacy, the gaps in our collections, and the resulting archival silences.

Conclusion

The collaboration between faculty, students, archives staff, and Wiki Ed produced a successful project from both pedagogical and archival perspectives. It opened doors for students to engage deeply with feminist scholarship as they created content for Wikipedia on topics related to gender and sexuality. The topics chosen from within the archives were carefully selected to address gaps in Wikipedia. This approach led to important conversations with students about how sexist, racist, and other forms of bias are expressed in Wikipedia. As students became more confident as editors, they were able to identify and address more complex issues of bias: for example, the shortage of articles that focus on women and other underrepresented groups, the types of information certain articles emphasized, and the ways in which all that information was linked within Wikipedia. In individual meetings and in-class sessions, students discussed how these gaps are created and how their role as editors was vital in helping to fill them. Students also benefited from sharing their experiences with the Connecticut College community: they came to see themselves as knowledge-producers, educating others about the biases and gaps in Wikipedia, as well as about the potential of the platform.

This project also provided a supportive environment for students to undertake archival work. By collaborating closely with archival staff, students experienced first-hand the complexities of archival research, engaging with archivists on issues of collection development, privacy, copyright, and gaps in archival records. In addition, the project generated opportunities for discussion about what materials from these collections could be used as citable evidence in Wikipedia articles. These exchanges made working in the archives a richer experience for students and staff.

The ongoing pedagogical value of this project is clear to Connecticut College’s GSIS department. Now in its fourth iteration, under the direction of a new GSIS faculty member, the project has become a core component of the department’s approach to teaching feminist theory. This project is a flexible, extensible way for students to directly engage in feminist praxis, providing students with the opportunity to address real-world inequalities in Wikipedia and to consider how their own research is informed by feminist theory. The project has the flexibility to expand by incorporating the use of digitized collections from other institutions to explore topics and content not held in the Lear Center. This extension has exciting possibilities for students as they explore different collections and learn about the differences and similarities in using analog and digital collections. For faculty and archival staff, this project deepened an already positive working relationship and inspired further exploration of digital humanities work in other classes.