Introduction

In an environment of rapid change in higher education in which institutions strive to lure prospective students with unique curricula, there is an increasing need to provide innovative pedagogical experiences for students through collaborations among libraries, archives, and digital humanities. There is also a growing body of literature—on research support for scholarship, curriculum development, collaborative publishing, and on shared values across these organizations and disciplines—about how historians, librarians, archivists, and digital humanists can forge mutually supportive relationships (Locke 2017; Middleton and York 2014; Rutner and Schonfeld 2012; Svensson 2010, para. 39; Vandgrift and Varner 2013). Kent Gerber (Digital Library Manager) Diana Magnuson, (archivist at the History Center and historian), and Charlie Goldberg (Digital Humanities coordinator and historian), are colleagues who set out to do just that at Bethel University, a small Christian Liberal Arts university in St. Paul, Minnesota. Applying insights from these literatures to the ever-evolving landscape of humanities teaching in higher education, the three planned an integrated set of assignments and projects that spanned a new “Introduction to Digital Humanities” course. “Introduction to Digital Humanities” was the first course in the new Digital Humanities major, and was designed to: engage and motivate students early in the curriculum with “hands-on, experiential, and project-based learning … where students think critically with digital methods” (Burdick et al. 2012, 134); “develop a broader set of skills … essential to students’ success in their future careers” (Karukstis and Elgren 2007, 3); and give students meaningful experiences and agency as a form of “professional scholarship” rather than placing them in a position of fulfilling “menial labor in a large-scale project” (Murphy and Smith 2017, para. 8). Our thinking about the design of this course was influenced by the pedagogical theory of Brett D. Hirsch, Paolo Freire, and Claire Bishop (Murphy and Smith 2017). Collaborative teaching always poses special challenges, but we anticipated that our diverse backgrounds and training would result in a rewarding and distinctive experience for our students.

This article will explain how we developed this signature course and curriculum in the context of a liberal arts university, and illuminate how it capitalized on relationships forged among the archives, the library, the history department and the digital humanities program. Built on the foundation of the material holdings of the History Center (Magnuson), the Digital Library (Gerber) was able to grow connections and extend the reach of these materials through an infrastructure of digital skills and collections. This combination provided a robust environment for the campus community to seek and eventually establish a Digital Humanities program, including a new major and a new faculty member (Goldberg) to develop and coordinate the program. The curriculum developed along the lines of Cordell’s four principles of how to incorporate digital humanities into the classroom, including starting small, integrating when possible, scaffolding everything, and thinking locally (2016). These relationships and principles enabled the development of a course, “Introduction to Digital Humanities,” which engages the archives, the digital library, and digital humanities domains in a mutually supportive and emergent cycle of learning and research.

Opportunities for undergraduate digital humanities scholarship and pedagogy are burgeoning, particularly at more prestigious liberal arts institutions. Occidental College in California, Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, and Hamilton College in New York all maintain well-funded centers for either Digital Liberal Arts or Digital Humanities focused on undergraduate students. There are also several noteworthy inter-institutional collaborations among liberal arts schools—COPLACDigital (comprised of more than twelve schools), the Five Colleges of Ohio (Oberlin College, Denison University, Kenyon College, Ohio Wesleyan University, and the College of Wooster), the Five Colleges Consortium in New England (Amherst, Hampshire, Mount Holyoke, and Smith Colleges, and the University of Massachusetts Amherst) and St. Olaf, Macalester, and Carleton Colleges in Minnesota have all received collaborative grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

At schools (like our own) that lack these resources, it can sometimes feel like the unique pedagogical opportunities afforded by this support are beyond the reach of faculty and staff. Our aim here is to describe our collaborative experiences and provide other scholars with a model of how the archive can intersect with digitization efforts and undergraduate pedagogy at smaller institutions of higher education. Together, these assignments and projects produced learning outcomes related to concepts in the humanities, archival research methods, digital competencies, information literacy, and digital humanities tools and software (Association of College and Research Libraries 2016; Bryn Mawr College n.d.).

History Center

The History Center, the archives at Bethel University, contains the institutional records of the university and its founding church denomination, known as Converge (formerly the Baptist General Conference). The History Center provides stewardship of manuscript and digital materials, collects historically relevant materials, curates three-dimensional objects, offers access to special collections, assists researchers, documents the story of its institutions and supports the mission of Bethel University and Converge. The types of collections housed at the History Center include but are not limited to: institutional records of Bethel University (college and seminary); Baptist General Conference (and all its iterations) minutes and annual reports; conference and university publications; church and district records (from both active and closed churches); home and foreign mission records; Swedish Bibles and hymnals; bibliographic records on conference pastors and lay persons; photographs and other media.

The director of archives at Bethel University (Magnuson) is a part-time position created in 1998 and held by a full time faculty member in the history department. This dual appointment provides unique positioning for the faculty member to provide a bridge for students between academic and public history. Students in her classes work with a variety of primary source materials, regardless of the level of the history course. Through the faculty member’s engagement with students in the classroom, Magnuson identifies students with proclivity for detail, curiosity about archival work, and willingness to explore a variety of primary source material. Sometimes, just by working with primary sources, or hearing a description of archival work or records management, a student reacts enthusiastically to the physical and intellectual encounter: “This is so cool, where can I have more of this kind of experience?” Over and over again, the experience of encountering a primary source in its original form is at once awe inspiring and profoundly transformative for the student. It is one thing to read about one of the first professing Baptist believers in nineteenth century Sweden and the impact this life had on Swedish Baptists in America, but it is quite another kind of experience to encounter in person the artifact of his diary (Olson 1952).

Two or three students each year are invited to work with the director of archives as student archive assistants. Students with a major or minor in history are given preference in the application process. Once hired, over the course of an academic year, students are exposed to and trained in: initial stages of archival control; digital inventory projects; arrangement and description; digital metadata entry; and patron assistance. For example, our students have contributed to developing collections focusing on photographs, film, artifacts, institutional records such as catalogs, yearbooks, and student publications.

In 2009 Bethel University hired someone for the newly created position of Digital Library Manager (Gerber). Since then, both the History Center and the Digital Library have transformed into dynamic learning laboratories for our undergraduate students to experience first-hand the tools of the professions of history and digital librarianship. The now nearly decade-long partnership between the History Center and the Digital Library is characterized by lively and productive collaboration on a number of fronts. For example, students hired by the history department are trained and work with both the Director of Archives and the Digital Library Manager. Major equipment that benefits both the History Center and the Digital Library has been purchased through mutual consultation and contribution of funding, such as an overhead book scanner and 3D scanner. Monthly meetings identify and move forward projects, workflow, grant applications, institutional initiatives, web presence, and troubleshooting as the need arises. At the behest of the Director of Archives and the Digital Library Manager, two foundational committees were formed to anchor our institutional conversations about our cultural heritage: the Cultural Heritage Committee and the Digital Library Advisory Committee, respectively. These committees support the History Center and the Digital Library through institution-wide input, drawing committee members from faculty, staff, and administration. In tandem we are significantly growing the breadth, depth, and reach of our collections, not only to our Bethel community, but to the world.

The Digital Library as Infrastructure and Bridge between the Archive and the Classroom

Of the Bethel Digital Library’s twenty-six collections spanning five major themes—Bethel History, Art and Creative Works, Faculty and Student Scholarship, Natural History, and the Student Experience—the majority of the content comes from the cultural heritage materials held in the History Center. Digitization of these unique materials broadens their availability to the community for teaching and research while simultaneously preserving the originals from wear because they do not need to be handled as frequently. Regular conversation between the Digital Library Manager and the Director of the Archives developed the library and archive as an infrastructure of values, practices, and workflows enabling a deeper understanding of Bethel’s cultural holdings and a broader reach of those materials to the Bethel community and beyond (Gerber 2017; Mattern 2014). In one of his series of four seminal articles on digital humanities, Director of the HUMLab in Umea University, Patrick Svensson discusses how the research-oriented infrastructure of technology, relationships, and practices, called “cyberinfrastructure” can be built specifically for humanities teaching and research (2011). Magnuson and Gerber’s collaboration developed a cyberinfrastructure at Bethel with the scanners, software, networked computing, meetings, digital collections, and committees mentioned above. The shape and scale of these resources influences a broad range of digital humanities literacies and competencies, as Murphy and Smith point out in their introduction to the special issue of Digital Humanities Quarterly focused on undergraduate education (2017, para. 7).

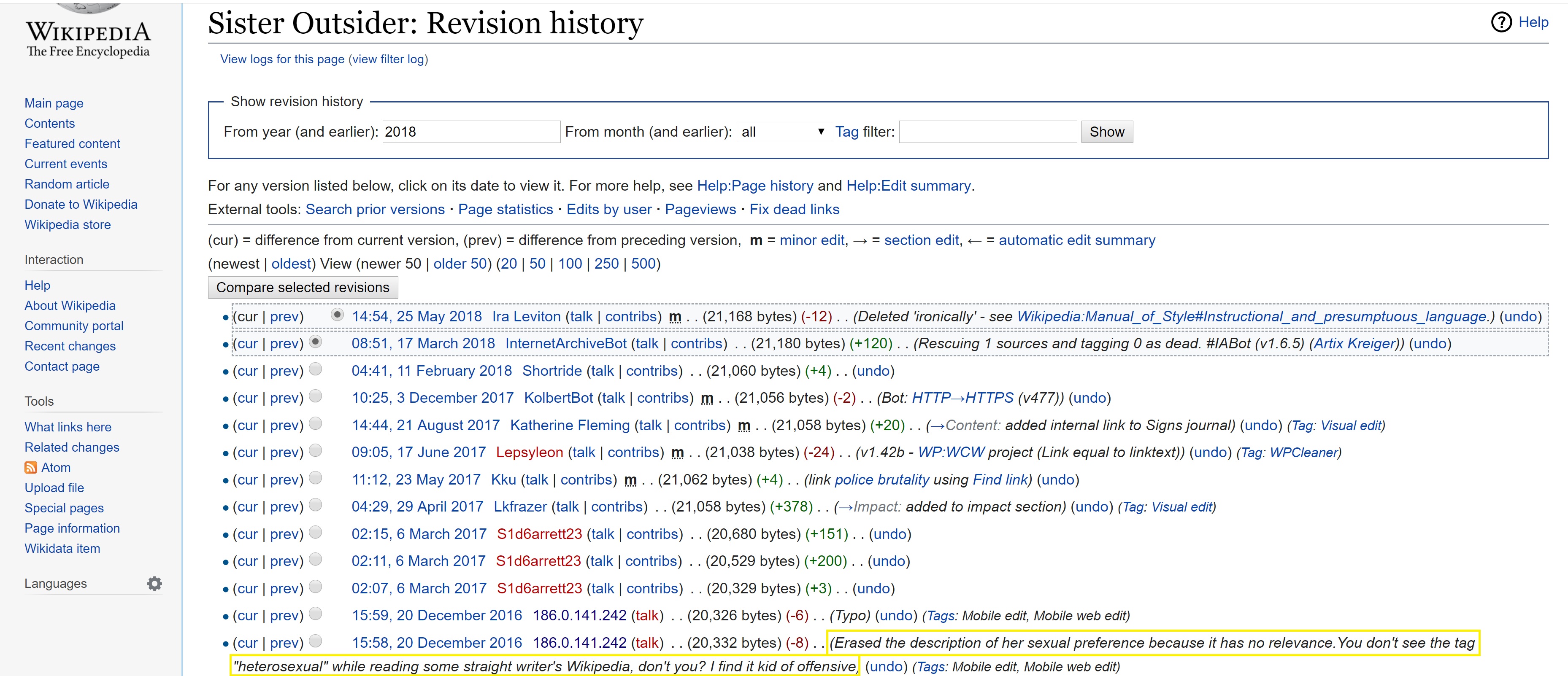

Bringing student workers into this cyberinfrastructure of the Digital Library and History Center also continued this cooperation and cross-pollination of knowledge and skills, and introduced them to information literacy skills and digital competencies. The first set of concepts these students learn are aspects of the Association of College and Research Libraries Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education. Information literacy is “the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning.” Knowledge of these skills has particular potency due to the influence of Mackey and Jacobson’s (2014) concept of “metaliteracy,” which expanded on information-literacy abilities with respect to the networked digital environment, rapidly changing media, increased consumption and production of media, and critical reflection upon one’s self and the information environment (ACRL 2015, para. 5). The Framework consists of six frames, or core concepts, of information literacy, which are marked by certain knowledge practices and dispositions when a learner moves through a threshold of awareness from novice to expert. The six frames are, in alphabetical order: 1) Authority is Constructed and Contextual; 2) Information Creation as a Process; 3) Information Has Value; 4) Research as Inquiry; 5) Scholarship as Conversation; 6) Searching as Strategic Exploration.

Digital competencies, as developed at Bryn Mawr College, are a useful complement to information literacy, spanning media and disciplines, specifically focused on the digital environment, and developed within the context of a small, liberal arts college. This model of skills is organized into five focus areas and can be used as learning objectives or as descriptions of skills one already has. The five focus areas are: 1) Digital Survival Skills; 2) Digital Communication; 3) Data Management and Preservation; 4) Data Analysis and Presentation; and 5) Critical Making, Design, and Development (Bryn Mawr, n.d.).

Informed by their work in the archives with historical materials, student workers in the archive and the Digital Library are exposed to and develop skills and competencies related to the above ACRL information literacy frames and the Bryn Mawr digital competencies. They accomplish this through learning the processes of digitization, learning how to use scanning equipment and image manipulation software, writing descriptive metadata, and encoding finding aids in a version of XML called Encoded Archival Description (EAD) for public display. Going through these processes introduced students to information literacy frames of “Information Creation as a Process” and “Information has Value” as well as digital competencies like “Digital Survival Skills,” “Data Management and Preservation,” and “Data Analysis and Presentation” (Association of College and Research Libraries 2016; Bryn Mawr, n.d.). As students begin work with the Digital Library, they begin to realize the limit of their own skills and abilities with technology and recognize how they can grow their awareness and competencies with “Digital Survival Skills,” particularly in the subcategory of “metacognition and lifelong learning.” The competency of “Data Management and Preservation” included learning more sophisticated hardware like flatbed scanners and the software environment of spreadsheets. The flatbed scanner process involved scanning at a high enough resolution for the resulting image to represent the original in print or digital formats as well as enable the ability to zoom in for very close examination afforded by a digital format. Some students had not used spreadsheets before and learned how to navigate a spreadsheet and use them to organize different categories of data and store multiple records of items. Students were introduced to the domain of “Digital Analysis and Presentation” through classification methodologies and learned how to navigate a digital archive to research a topic of interest. The skills students learned from these experiences motivated them to learn more and prepared them for further study in graduate school or employment in the cultural heritage sector. This built a culture of trust, common understanding, and shared competencies between both units and set a foundation for further integration of Bethel’s cultural heritage in the classroom and the establishment of the Digital Humanities major (Bryn Mawr College n.d.).

While these competencies and literacies were building in student workers, it was necessary to integrate the learning of these concepts more broadly into the general curriculum so that more students could benefit. Some classroom opportunities emerged as a result of the digitization activities in various classes and disciplines. Students researched historical events and trends through their increased access to documents within a collection like the historical student newspaper collection for their journalism projects, engaging the frames of “Research as Inquiry” and “Searching as Strategic Exploration.” Students in a computer science course on data mining were also able to use the corpus of metadata from collections like the student newspaper, college catalogs, and faculty research as an object of study in their projects to identify trends in course offerings, changes in campus space, changes in school mascots through the years, and profiles of particular individuals in Bethel’s history. These assignments and experiences also built some familiarity with ways to engage archival material in classes other than a history class. Some of these students were excited to make these discoveries and had a heightened interest in the history of the institution, but their ability to pursue it in any depth was limited by the length of one single assignment.

In 2017, two developments in Bethel’s cyberinfrastructure improved the scope and scale for student learning anchored in these concepts: the launch of Bethel’s Makerspace in the Library and the creation of a Digital Humanities major. Bethel’s Makerspace is the result of a purposeful design discussion consisting of a cross-disciplinary group of faculty, staff, and administrators. This discussion resulted in a technology-infused space in the Library to explore innovative, creative technologies and encourage collaboration and experiential classroom experiences through the use of 3D scanners, 3D modeling and media production software, photo studio equipment, movable furniture, 3D printers, and meeting space for groups and classes. With the Digital Humanities program in place beginning in 2017, a new opportunity emerged for students to use the Makerspace as a lab to learn information-literacy concepts and digital competencies as demonstrated by other programs (Locke 2017, para. 8–49; White 2017, 399–402), and to engage more fully in the physical archive and the digital collections.

The Archive in Digital Humanities Pedagogy

Powerful technology has never been more accessible to educators, even, as we describe above, to educators at smaller schools like our own. Yet there remains the assumption that the digital humanities are best left to R1 institutions with deep pockets and deep rosters of instructors and support staff (Alexander and Frost Davis 2012; Battershill and Ross 2017, 13–24). However, there is a growing conversation and community of practice for undergraduate and liberal-arts–oriented digital humanities education, like the Liberal Arts Colleges section of the Digital Library Federation, that seeks ways for smaller institutions to thrive (Buurma and Levine 2016; Christian-Lamb and Shrout 2017; Locke 2017, para. 7). Bethel has been able to do this through incremental financial investments in technology and intentional partnerships like the efforts of the History Center and Digital Library mentioned above. In 2016–2017, Bethel designed and launched a new undergraduate Digital Humanities major informed by concepts from digital humanities pedagogy that capitalized on the existing technical and relational investments that can be available to faculty at most institutions with limited means (Brier 2012; Cordell 2016; Wosh, Moran, and Katz 2012).

We have benefited greatly by our archival holdings in the History Center. A particular challenge to incorporating digital humanities in the classroom is avoiding the technological black hole, whereby the technology used to make something becomes the focus of the thing itself, demanding the attention of both instructor and student at the expense of the humanistic subject. The archive, as an essential repository of humanistic data, can help anchor the traditional humanities at the center of digital humanities pedagogy. Here, we share an example of a lesson plan that aims to do just this—to craft an undergraduate archival project that is at once technologically sophisticated yet true to traditional humanistic values—all without the use of expensive equipment.

This project was inspired by a research trip Goldberg made to Rome as a graduate student at Syracuse University. On a day off from research, he visited Cinecittà, a large film studio just outside the city that housed the set for the 2005 HBO series Rome. The studio still maintains the set, featuring a scale replica of the ancient Roman forum, and allows visitors to traipse the grounds as part of a tour. As a Roman historian, standing in a replica of the forum was a powerful experience for Goldberg, and delivered a new sense of historical place and space that examining traditional scholarly materials—maps, plans, and written descriptions—couldn’t match.

When Goldberg arrived at Bethel in the Fall of 2016 and began designing the Digital Humanities curriculum, he looked for ways to emulate his experience abroad. Digital 3D modeling, including virtual reality applications, can provide such an immersive experience for the viewer, and holds a special value for bringing archival materials to life (Goode 2017). Working in tandem with Magnuson and Gerber, it became apparent that the History Center archive contained a treasure trove of materials pertaining to the university’s spatial past: photographs of historical groundbreaking ceremonies, architectural blueprints, and design sketches. Particularly alluring were plans and renderings for campus expansions that never panned out; such materials suggested alternative campus realities that would have fundamentally altered the contexts of how students, faculty, and staff interact with one another on a daily basis.

During a summer meeting in the History Center, we began to design a six-week lesson plan for Goldberg’s semester-long Introduction to Digital Humanities course. Our primary pedagogical goals were twofold: 1) to introduce students to archival digitization practices, culminating with the creation of digital records for traditional archival materials; and 2) to create immersive, experiential worlds based on the History Center’s architectural records. We determined that Trimble’s Sketchup, a 3D modeling program used by architects, interior designers, and engineers, was the best software tool for goal #2. Even more, Trimble provides 30-day trial versions of its Pro software for educators and students, long enough to cover the three weeks dedicated to 3D modeling in this assignment. They also now offer Sketchup for Web, an entirely online, cloud-based version of the software, which eliminates the need to install the software on campus or student computers, though it does lack certain key features of the Pro version.

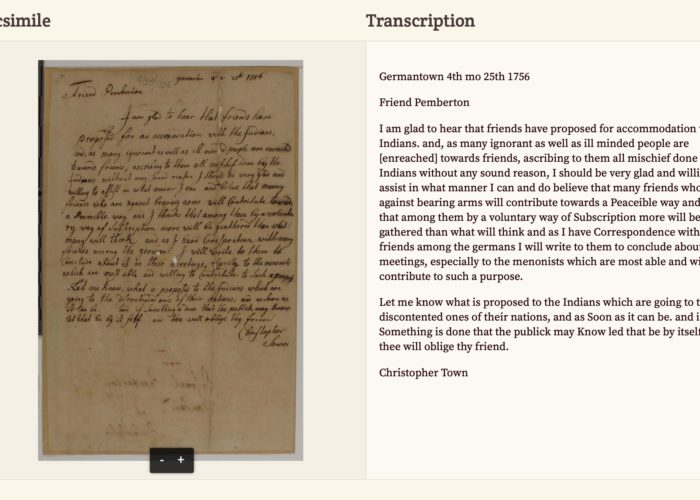

For this assignment, students chose a building, actually built or only existing in design plans, from the campus’s present or past. They chose two photographs or other visual records of it from the History Center (such as blueprints or design illustrations), and were tasked with incorporating these as entries into the Digital Library. This aspect of the assignment was structured over three weeks, and gave students an introduction to many of the professional archival practices and digitization fundamentals described above, providing a hands-on “experiential” learning opportunity that immersed them in the fabric of our institutional history. Finally, students were to create 3D digital models of their structure using Sketchup. This final step also took three weeks.

As Digital Library manager, Gerber took the lead in the first half of the assignment. Because most students were freshmen, we assumed no previous exposure to the archival setting. We therefore took a field trip to the History Center, where Magnuson gave an overview of her work there and introduced students to basic archival practices. We then reassembled as a class to learn some basic digital competencies like how medium impacts the experience and the meaning of an archival item by comparing and contrasting physical and digital versions of the same object. Once introduced to this framework, the class focused on how any object, be it a photograph, document, or physical object, possesses a range of features unique to it and how to attach a description of it to a digital file in order to be intelligible and findable by both humans and computers. To use a nonarchival example, an action figure is made of a certain material (e.g., “plastic”), is a certain size (e.g. “8 inches tall”), made by a certain company (e.g., “Mattel”), in a certain year. This basic principle is a crucial aspect of proper digital asset management, and allowed us to introduce the concept of “metadata,” or information about an object that describes its characteristics. We stressed the importance of metadata in the archival setting and introduced our students to the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative, an international organization dedicated to maintaining a standard and best practices for describing and managing any kind of information artifact including archival material. At its heart, Dublin Core consists of fifteen common elements necessary to describe the metadata of any archival object (e.g., “Title,” “Creator,” “Subject,” “Description,” etc.). We then looked at how items catalogued in the Digital Library store this metadata and apply local standards, like the Bethel Digital Library Metadata Entry Guidelines, adapted from the Minnesota Digital Library Metadata Entry Guidelines, to determine what kind of information is needed in each element. We focused particularly on the purpose of the Title and Description elements in the Historical Photographs Collection and analyzed the quality of the entries based on how well they provided context and facilitated discovery of the item by a potential researcher. For example, the Title element for the image of Esther Sabel, a prominent woman in Bethel’s history, was used to demonstrate levels of quality seen in Table 1: Poor – “Woman,” Good – “Portrait of Esther Sabel,” Better – “Portrait of Esther Sabel, Head of Bible and Missionary Training School.” Finally, based on this scaffolding, students were given the assignment of analyzing two images in the Historical Photographs Collection with insufficient or erroneous metadata, and improving the records in this Metadata Improvement Worksheet using a shared Google Spreadsheet.

| Poor Descriptive Titles | Good Descriptive Titles | Better Descriptive Titles |

|---|---|---|

| These titles lack specificity and do NOT assist users in finding materials. | These are examples of basic descriptive titles. | These titles provide users with more specific information and relay exactly what is in the image. |

| Woman | Portrait of Esther Sabel | Portrait of Esther Sabel, Head of Bible and Missionary Training School |

| Crowd of People | Group of students sitting on grass | Group of seven students outside signing yearbooks |

In the second week, we gathered several folders of photographs, blueprints, and architectural renderings awaiting catalogue entry in the History Center, and had our students spend some time perusing their contents. Since the assignment was quite long at six weeks and culminated in a large finished digital work that some students found intimidating, we found that students greatly appreciated this unstructured exploration, or “tinkering” (Sayers 2011) time. These photographs provided intimate glimpses into the university’s past and unrealized future(s), and motivated our students to find out more about the students who came before them. Students then selected two images for entry into the Digital Library, and received their second assignment: tracking down the necessary metadata. Their submissions would become a publicly-available part of the Historical Photograph Collection, adding a “real-world” application incentive to this assignment. Some images were easier to provide metadata for than in others, with dates or a list of subjects written on the back. Photographs of ground-breaking ceremonies could be dated by looking up construction dates for buildings on campus. Others required reasoned speculation. Dates for difficult photographs could be estimated by the style of clothing of the people photographed, for example.

In the third week, students wrote a two- to three-page blog post synthesizing Digital Library records into a narrative of a past campus event. Some students chose to write on their dorms or the campus building they had previously studied, while others wrote on a key historical event, such as Martin Luther King Jr.’s scheduled visit to campus in the 1960s. This aspect, since it required close reading of a text or texts, was the component of the assignment most aligned with the traditional humanities, and helped alleviate some anxiety in the instructors that this digital-centered project might stray from core humanities values.

In the second half of the assignment, students created three-dimensional digital models of their campus building using Trimble’s Sketchup. Sketchup is a popular software tool with an active and enthusiastic online support community. Having access to a wide range of tutorial walkthroughs and videos greatly reduced the learning curve for acclimating both instructor and student to the software. There are also several guides and tutorials written specifically for those in the digital humanities community, which provide helpful tips for applying it to the humanities classroom. In particular, Goldberg benefited from the step-by-step guide for creating 3D models from historical photographs written by Hannah Jacobs at Duke University’s Wired! Lab, as well as Kaelin Jewell’s use of Sketchup to bring medieval building plans to life (Jewell 2017). We have made Goldberg’s intro and advanced tutorials available online. The fourth week was devoted to installing Sketchup on student computers and learning the basics. Students with experience playing video games tended to get up to speed faster than others, as the software’s simulated three-dimensional environment can be disorienting at first. Students, and instructors, should be encouraged to simply search Google if there is a particular process they are struggling with, since there are many helpful tutorials on YouTube.

After we learned the basic functionality, we began to translate our photographs into architectural models in Sketchup. The program allows the user to upload an image and transform the two-dimensions represented within it into three dimensions of digital space. It does this by insinuating axis lines on the image, and “pushing” the façade of the building back into a third dimension, as demonstrated in these two photos:

Because this process involves transforming a two-dimensional image into three-dimensional space, it is imperative to start with the right kind of image. The one used above demonstrates the proper perspective; essentially, the image must contain a vanishing point. Head-on images do not allow the user to determine how deep the actual physical building is and are therefore not usable in this process.

Next, the user can begin to add features to their model, referring back to the two-dimensional image as necessary. In our class, we allowed students two additional weeks to complete this process. We found this to be necessary since none of our students were previously familiar with Sketchup. This time therefore allowed them to troubleshoot errors as they came up. Class time was dedicated to working on our models together. Students and instructors collaborated with one another and shared strategies and tips. Finally, the completed models were rendered with V-Ray, a plugin for Sketchup which places the models in simulated environments, adding convincing lighting and other scenery effects.

Many projects succeeded. Graham McGrew, for example, started with an unbuilt plan from the 1960s for an A-frame building to house the university’s seminary chapel, as shown in this final rendered image:

Another student, Bobbie Jo Chapkin, chose to model the existing Seminary building, as shown in this final rendered image:

There are clear challenges to incorporating archival practices into digital humanities pedagogy. Regarding our lesson here, students lacking familiarity with video games or other three-dimensional computing tools may find orienting themselves to Sketchup challenging. And, as with any large project, the quality of the final products will depend entirely on the effort and energy students put in. Still, this project successfully combined a focus on the humanistic value of the archive with a modern software application to create a sophisticated experience that recreated an episode from our past campus.

Expanding from this specific project to consider the collaborative efforts described here generally, the intersection between three diverse academic disciplines might be thought to be a difficult place for three busy researchers and teachers to land upon. However, we feel that the best strategy for effecting meaningful interdisciplinary pedagogy in the archive and the humanities is to encourage organic opportunities to develop at their own pace, and to scaffold larger projects such as this one upon the foundations already laid. Our efforts were long in the making—Bethel’s archivist position was created in 1998, its digital librarian position in 2009, and its Digital Humanities position in 2016. Rome, even as a modern HBO set, wasn’t built in a day. Though incorporating the traditional archive into digital undergraduate pedagogy is a relatively recent effort, it still rests primarily on tried-and-true humanities principles like thoughtful reading, analysis, and attention to detail.