Reading and Digital Technologies: A New Challenge

It seems impossible to imagine a world where digital technologies are not a substantial part of our intellectual activities. The use of technology in teaching and learning is becoming increasingly prominent, even more now, as the massive public health crisis of COVID-19 created the need to access information without physical proximity. Yet, the way information is processed on digital platforms is substantially different from the cognitive standpoint, and not exempt from concerning consequences: recently, it has been emphasized that accessing content digitally stimulates superficial approaches and “skimming”, rather than reading, which may have a longstanding impact on the ways in which human brains understand, approach, and articulate complex information (Wolf 2018).

Therefore, we must ask ourselves if we are using digital technologies in the right way, and what can be done to address this problem. Instead of eliminating digital methods entirely (which in current times seems especially unrealistic), maybe the solution resides in using them to empower a different way of approaching information. In this paper, I will advocate that the practices embedded in the study of Classical texts can offer a new perspective on reading as a cognitive operation, and that, if appropriately empowered through the use of technology, they can create a new and meaningful approach to reading on digital platforms.

The study of Classical languages implies a very peculiar approach to processing information (Crane 2019). The most relevant aspect of studying Classical texts is that we cannot consult a native speaker to verify our knowledge: instead, “communication” is achieved through written sources and their interaction with other carriers of information, such as material culture and visual representations. On the other hand, we must never forget that we are engaging with an alien culture to which we do not have direct access. This necessity of navigating uncertainty requires a much more flexible approach to information, and a very different way of engaging with written sources, where the focus is on mediated cultural understanding through reading, rather than immediate communication.

Engaging with an ancient text is a deeply philological operation: a scholar of an ancient language never simply goes from one word to another with a secure understanding of their meaning. Their reading mode is much more immersive. It is an operation of reconstruction through reflection, pause, and exploration, which requires several skills: from the ability of active abstraction of the language and its mechanics, to the recognition of linguistic patterns that coincide with given models, to the reflection on what a word or expression “really means” in etymological, stylistic, and cultural terms, to the philological reconstruction of “why” that word is there, as a result of a long process of transmission, translation, and error.[1] Yet, the implications of this intensive reading mode, in the broader context of the cognitive transformations to reading and learning, are often overlooked.

The operations embedded in the reading of Classical languages respond to a different cognitive process, that is beyond the opposed categories of “skimming” and traditional linear reading. Because of this peculiarity, some of the technologies designed in the domain of Classical languages are created specifically to empower this approach, bringing it at the center of the reader’s experience.

Translation Alignment: Principles and Technologies

Digital technologies are widely used in Classics for scholarship and teaching, thanks to the widespread use of digital libraries like Perseus (Crane et al. 2018) and the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (2020), and to the consolidation of various methods for digital text analysis (Berti 2019) and pedagogy (Natoli and Hunt 2019). One of the most interesting recent developments in the field is the proliferation of platforms for manual and semi-automated translation alignment.

Translation alignment is a task derived from one of the most popular applications in Natural Language Processing. It is defined as the comparison of two or more texts in different languages, also called parallel texts or parallel corpora, by means of automated or semi-automated methods. The main purpose is to define which parts of a source text correspond to which parts of a second text. The result is often a list of pairs of items – words, sentences, or larger texts chunks like paragraphs or documents. In Natural Language Processing, aligned corpora are used as training data for the implementation of machine translation systems, but also for many other purposes, such as information extraction, automated creation of bilingual lexica, or even text re-use (Dagan, Church, and Gale 1999).

The alignment of texts in different languages, however, is an exceptionally complex task, because it is often difficult to find perfect overlap across languages, and machine-actionable systems are often inefficient in providing equivalences for more sophisticated rhetorical or literary devices. The creation of manually aligned datasets is especially useful for historical languages, where available indexes and digitized dictionaries often do not provide a sufficient corpus to develop reliable NLP pipelines, and are remarkably inefficient for automated translation. Therefore, creating aligned translations is also a way to engage with a larger scholarly community and to support important tasks in Computer Science.

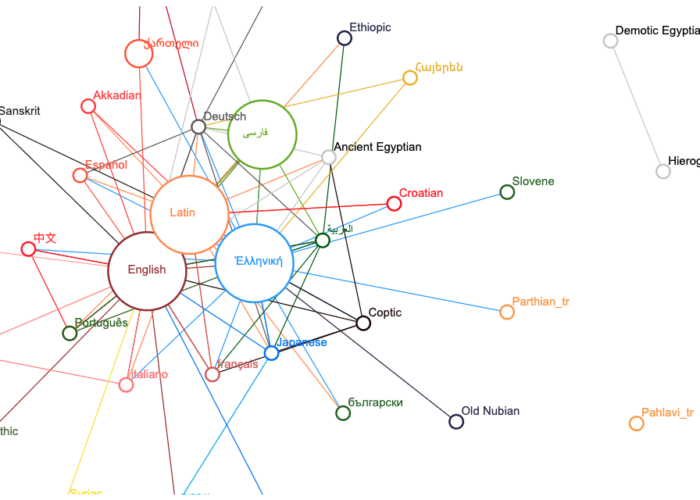

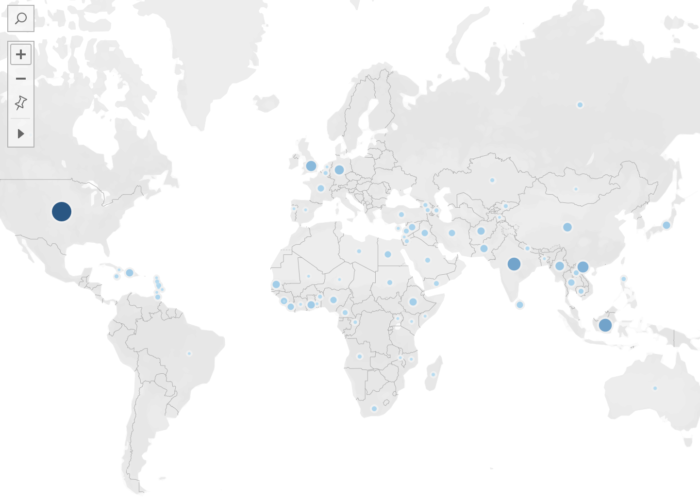

In the past few years, three generations of digital tools for the creation and use of aligned corpora have been developed specifically with Classical languages in mind. First, Alpheios provides a system for creating aligned bilingual texts, which are then combined with other resources, such as dictionary entries and morphosyntactic information (Almas and Beaulieu 2016; “The Alpheios Project” 2020). Second, the Ugarit Translation Alignment Editor was inspired by Alpheios in providing a public online platform, where users could perform bilingual and trilingual alignments. Ugarit is currently the most used web-based tool for translation alignment in historical languages: since it went online in March 2017, it has registered an ever-increasing number of visits and new users. It currently hosts more than 370 users, 23,900 texts, 47,600 aligned pairs, and 39 languages, many of which ancient, including Ancient Greek, Latin, Classical Arabic, Classical Chinese, Persian, Coptic, Egyptian, Syriac, Parthian, Akkadian, and Sanskrit. Aligned pairs are collected in a large dynamic lexicon that can be used to extract translations of different words, but also as a training dataset for implementing automated translation (Yousef 2019).

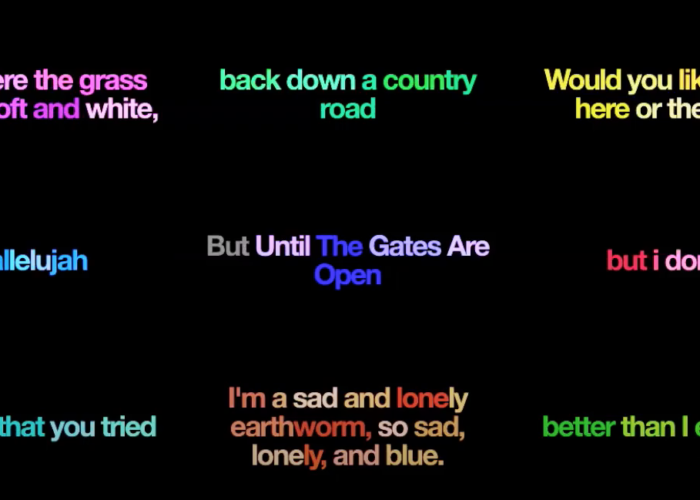

The alignment interface offered by Ugarit is simple and intuitive. Users can upload their own texts and manually align them by matching words or groups of words. Alignments are automatically displayed on the home page (although users can deactivate the option for public visibility). Corresponding aligned tokens are highlighted when the pointer hovers on them. The percentage of aligned tokens is displayed in the color bar below the text: the green indicates the rate of matching tokens, the red the rate of non-matching tokens. Resulting pairs are automatically stored in the database, and can be exported as XML or tabular data. For languages with non-Latin alphabets, Ugarit offers automatic transliteration, visible when the pointer hovers on the desired word.[2]

The structure of Ugarit was also used to display a manually aligned version of the Persian Hafez, in a study that tested how German and Persian speakers used translation alignment to study portions of Hafez using English as a bridge language. The results indicated that, with the appropriate scaffolding, users with no knowledge of the source language could generate word alignments with the same output accuracy generated by experts in both languages. The study showed that alignment could serve as a pedagogical tool with a certain effect on long-term retention (Palladino, Foradi, and Yousef forthcoming; Foradi 2019).

The third generation of digital tools is represented by DUCAT – Daughter of Ugarit Citation Alignment Tool, developed by Christopher Blackwell and Neel Smith (Blackwell and Smith 2019), which can be used for local text alignment and can be integrated with the interactive analysis of morphology, syntax, and vocabulary. The project “Furman University Editions” shows the potential of these interactive views, which are currently part of the curriculum of undergraduate Classics teaching at Furman and elsewhere.

This proliferation of tools shows that there is potential in the pedagogical application of this method: translation alignment can provide a new and imaginative way of using translations for the study of Classical texts, overcoming the hindrances normally associated with reading an ancient work through a modern-day version.

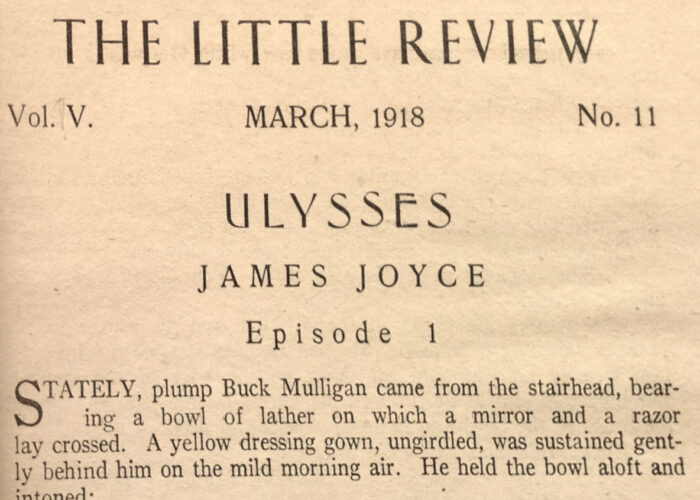

Text Alignment in the Classroom

The use of authorial translations to approach Classical texts is normally discouraged in the classroom, being perceived as “cheating” or as unproductive for a true, active engagement with the language. Part of this phenomenon is explained by the fact that, as “passive” readers, we don’t have any agency in assessing the relationship between a translation and the original, and reading them side by side on paper is rarely a systematic or intentional operation (Crane 2019). However, translations are an integral part of ancient cultures.[3] They are a crucial component of textual transmission, as they represent witnesses of the survival and fortune of Classical texts. Translations are also important testimonies of the scholarly problem of transferring an alien culture and its values onto a different one, to ensure effective communication, or to pursue a cultural and political agenda through the reshaping and recrafting of an important text (Lefevere 1992).

Translations are a medium between cultures, not just between languages. Engaging in an analytical comparison between a translation and the original means to have a deeper experience of how a text was interpreted in a given time, what meanings were associated to certain words, and, at the same time, how certain expressions can display multifaceted semantics that are often not entirely captured by another language. This is also an exercise in cultural dialogue and reflection, not only upon the language(s), but upon the civilization that used it to reflect its values. In other words, it is a philological exploration that resembles much of the reading mode of a Classicist.

Digital platforms for translation alignment offer an immersive and visually powerful environment to perform this task, where the reader can analytically compare texts token by token, and at the same time observe the results through an interactive visualization. It is the reader who decides what is compared, how, and to what extent: the comparison of parallel texts becomes an analytical, systematic operation, which at the same time encourages reflection and debate regarding the (im)perfect matching of words and expressions. In this way, translation alignment provides a way to navigate between traditional linguistic mastery and the complete dependence upon a translation. Not only this stimulates an active fruition of modern translations of ancient texts, but the public visibility of the result on a digital platform also provides a way to be part of a broader conversation on the reception and significance of an ancient text over time.

However, it is also important to apply this tool in the right way. For example, translation alignment needs to be coupled with some grammatical input, to encourage reflection on structural linguistic differences. Mechanical approaches, all too easy with the uncontrolled use of a clickable “matching tool”, should be discouraged by emphasizing the importance of focused word-by-word alignment. In practice, translation alignment needs to be used with caution and in meaningful ways, as a function of the goal and level of a course.

The following sections illustrate examples of application of translation alignment in the context of beginner, intermediate, and upper level classes in Ancient Greek and Latin. Translation alignment was structurally used during the courses to emphasize semantic and syntactic complexities through analytical comparison with English or other languages. Later, students were assigned various alignment tasks and exercises, designed to empower an analytical approach to the text.

Beginner Ancient Greek, first and second semester

The students were given two assignments, performed iteratively in two consecutive semesters, with variations in quantity (more words and sentences were assigned in the second semester):[4]

- Individuate specific given words in a chosen passage, and align them with the corresponding words in one translation. The goal of this exercise was to set the groundwork to develop a rough understanding of the depth of word meanings, by assessing how the same word in the source text could appear in different ways across the same translation.

- Use alignment to evaluate two translations of a shorter text chunk (1–3 sentences, or 10 verse lines). Identify precisely the corresponding sections of text in the source and in the translations. Assess which translation is most effective by using two criteria: 1, combination of number and quality of matched tokens; 2, pick particularly problematic words and look them up in a dictionary, to assess their meanings; compare the dictionary explanation with the general context of the passage, and assess how translations relate to the dictionary entries and how closely they render the “original sense” of the word.

The results were two short essays where the students articulated their considerations. Grading was based on the ability to give insightful analysis of how word choices impacted the tone and meaning of the translations, and discuss the semantic depth of the words in the original language. Bonus points were provided if the student was able to identify tangential aspects, such as word order, changes in cases, and syntax. Minor weight was given to the overall accuracy of the alignment, in consideration of the level: the design of the exercises was deliberate in discouraging the creation of longer alignments, which often result in the student doing the work without thinking about their alignment choices. Essay questions focused instead on close-reading, analytical, in-depth investigation into the semantics of the source language.

Intermediate level of Ancient Greek and Latin, third semester

Students used translation alignment in the context of project-based learning. They were responsible for the alignment of a chosen text chunk against translations that they had selected, ranging from early modern to contemporary translations. The assignment was divided in phases:

- Alignment of the source text against two chosen translations in English, and systematic evaluation of both translations. The students were asked to focus on chosen phenomena of syntax, morphology, grammar and semantics, that were particularly relevant in the text: e.g. word order, participial constructs, adjectival constructs, passive/active constructions, changes in case, transposition of allusion and semantic ambiguity. The students used their knowledge of syntax and grammar to critically assess the performance of different translators, focusing on the different ways in which complex linguistic phenomena can be rendered in another language. This assignment was combined with side analysis of morphology and syntax: for example, the students of Ancient Greek designed a morphological dataset containing 200 parsed words from the same passage.

- Creation of a new, independent translation, with a discussion of where it distanced itself from the original, which aspects of it were retained, and how the problems individuated in the authorial translations were approached by the student.

The result was a written report submitted at the midterm or end of the semester, indicating: the salient aspects of the texts and its most relevant linguistic features; an analytical comparison of how those linguistic features appeared in the competing aligned translations, and an evaluation of the translator’s strategy; the student’s translation, with a critical assessment of the chosen strategy to approach the same problems. These aspects constituted the backbone of the grading strategy, with additional attention to the alignment accuracy.

Upper level Ancient Greek and Latin, fourth to seventh semester (graduate and undergraduate)

The exercises assigned for the upper level were a more articulated version of the project-based ones given to the intermediate level. The students were assigned a research-based project where alignment would be one component of an in-depth analysis of a chosen source. At an intermediate stage of the semester, the students would submit a research proposal indicating: an extensive passage they chose to investigate, and why they chose it; the topic they decided to investigate, and a short account of previous literature on it; methodologies applied to develop the project; desired outcomes. The final result would be a project report submitted at the end of the semester, indicating: if the desired outcomes had been reached, what kinds of challenges were not anticipated, and what new results were achieved; strategies implemented to apply the chosen methodology, e.g. which alignment strategy was applied to ensure that the research questions were answered; what the student learned about the source, its cultural context and/or language. The results were graded as proper projects: the students were evaluated according to their ability to clearly delineate motivation and methodology, use of existing resources, and critical discussion of the outcomes.

Many students creatively integrated alignment in their projects. For example:

- Creation of an aligned translation for non-expert readers, alongside a commentary and morphosyntactic annotations. To facilitate reading, the student developed a consistent alignment strategy that only matched words corresponding in meaning and grammatical function. This project was published on GitHub.

- Trilingual alignment of English-Latin-German to investigate the matching rate between two similarly inflected languages. The student noted that, even if their knowledge of German was inferior to English and Latin, matching Latin against German proved easier and more streamlined, while the English translation was approached with more criticism for its verbosity (Figure 4).[5]

- Trilingual alignment to compare different texts. The student conceived a project aimed at gathering systematic evidence of the verbatim correspondences between the so-called Fables of Loqman and the Aesopic fables: according to existing scholarship, the former would be an Arabic translation of the latter. The student used a French translation of the Loqman fables to leverage on the challenges of the Arabic, and examined the overall matching rate across the texts (see this sample passage).

Results

The students reported how alignment affected their understanding of the source and its linguistic features, and how approaching the original by comparing it against a modern translation gave them a deeper understanding and respect for the content. While the alignment process often resulted in some criticism of available translations, the students who had to discuss the challenges faced by translators (or who had to translate themselves) gained a stronger understanding of the issues involved in “transferring” not only words and constructs but also underlying cultural implications and multiple meanings. The students who used alignment in the context of research projects also benefited from the publication of their aligned translations, and some presented them as research papers at undergraduate conferences. Many students even reported to have used alignment independently afterwards in other courses, often to facilitate the study of new languages, both ancient and modern.

Some overarching tendencies in the evaluation of concurrent translations emerged, particularly at the Intermediate and Upper Level. This feedback was extremely interesting to observe, because most of it can only be explained as the result of a systematic comparison between target and source language, in a situation where the reader is an active operator and not a passive content consumer.

The students observed analytically the various ways in which translations cannot structurally convey peculiar aspects of the original: for example, dialectal variants, metrical arrangement, wordplays, or syntactic constructs. Most of them were still able to appreciate skillful modern translations, and even to diagnose why translators would distance themselves from the original. They definitely understood the challenge by engaging in translation tasks themselves. For many, however, the discovery that they could not fully rely on translations to understand what is happening in a text was astonishing. Students tend to be educated to the idea that authorial translations are necessarily “right” (and therefore “faithful”[6]) renderings of Classical texts, to the point where they often trust them over their own understanding of the language. With this exercise, they learned that “right” and “faithful” may not be the same thing, and that the literature of an ancient civilization preserves a depth and complexity of meaning that cannot be fully encompassed in a translation.

Interestingly, students often had a more positive judgement of translations that rendered difficult syntactic constructs more closely to the original without fundamentally altering the structure, or shifting the emphasis (e.g. by changing subject-object relations or by altering verb voices). Students at the Intermediate level, in particular, judged such translations more “literal”, as they found them more helpful in understanding important linguistic structures: Figure 3 shows an alignment of Hesiod’s Works and Days, where the student extrapolated adjective-noun combinations and participle constructs to draw a systematic comparison between two concurring translations. The translation that was judged “more literal”, and therefore more useful for a student, was the one that kept these structures closer to the way they appeared in the original. This phenomenon intensified with texts that had a strong amount of allusions and wordplay, which are often conveyed by means of very specific syntactic constructs: students who dealt with this kind of texts were merciless judges of translations that completely altered the original syntax and recrafted the phrasing to adapt it to a modern audience. The students indicated how such alterations regularly failed to convey the depths of sophisticated wordplay, where the syntax itself is not an accessory, but a structural part of the meaning.

The omission of words in the source language was considered particularly unforgiving: even though some words like adverbs and conjunctions are omitted in translations to avoid redundancies, some translations were found to leave out entire concepts or expressions for no apparent reason. The visualization of aligned texts on Ugarit certainly accentuated this aspect, as it tends to emphasize the relation between matched and non-matched tokens through the use of color, and it also provides matching rates to assess the discrepancy between texts. Almost all the students seem to have intensively taken advantage of this aspect, by emphasizing how translations missed entire expressions that appeared in the original and shaped its message: in other words, even if the omission only regarded one adjective or a particularly intensive adverb, they felt that translations did not convey the full meaning of the text they were reading.

The implications of such observations are interesting: the translations in question were “bad” translations not because they were not understandable or efficient in conveying the sense of a passage in English, but because they hindered the student’s understanding of the original. Readers, even classically-trained ones, normally enjoy translations that, while taking some liberties, are more efficient in conveying the content and artistic aspects of a text in a way that is more familiar to a modern audience. Students who read a text in translation often struggle with versions that try to be close to the original language (sometimes with rather clumsy results), and they also make limited use of printed aligned translations that used to be very popular in school commentaries of the past. However, when students became active operators of translation alignment, the focus shifted to the understanding of the original through the scaffolding provided by the translation. In other words, the focus was on how the translation served the reader of the source text: this suggests an extremely active engagement with the original, through the critical lenses of systematic linguistic comparison.

With the guidance provided by the exercises, the students used translation alignment to engage with linguistic and stylistic phenomena, and the assessment of the ineffectiveness of translations in conveying such complex nuances often made them more confident in approaching the original language. In their own translations, they became extremely self-aware of their position with respect to the text, and tried to justify every perceived variation from the structure and the style of the original. Some of them opted for very literal, yet clumsy, translations, which they reflected upon and elaborated more thoroughly in a commentary to the text; others, particularly at the Upper level, built upon aspects that they liked or disliked in the translations to create better versions of them, depending on their intended audience.

We can conclude that, if appropriately embedded in reflective exercises, translation alignment did not result in a mechanical operation of word matching, but nurtured an active philological approach to the text, and an exploration of it in all its different aspects, from linguistic constructs to word meanings, to the role of wordplays in a literary context. Despite growing skepticism in the ability of translations to convey the “full” meaning of a text, the students still believed in the necessity of using them in a thoughtful manner.

In fact, the students advocated for more and more varied use of digital tools, to compensate for the deficiencies of aligned corpora. At the Upper level in particular, many students complemented their translation alignments with additional data gathered through other digital resources: for example, while creating translation alignments directed at non-expert readers, they integrated the resource with a complete morphosyntactic analysis performed with treebanking (Celano 2019), with the intention of making up for the limitations of incomplete matching of word functions in specific linguistic constructs.

In this regard, it is important to emphasize that translation alignment is just one of the tools at our disposal. In a future where learning and reading are going to be prevalently performed through digital technologies, we need to create environments where readers can meaningfully engage in a philological exploration of texts at multiple levels: translation alignment, but also detection of textual variants, geospatial mapping, social network analysis, morphosyntactic reconstruction, up to the incorporation of sound and recording that can compensate for reading and visual disabilities (Crane 2019).

Conclusions

Overall, the experiment showed that a meaningful use of translation alignment can empower a reflective and active approach to Classical sources, by means of the continuous, systematic comparison of the cultural and semantic depths embedded in the language. Of course, translation alignment should not be the only option: digital technologies offer many opportunities of enhancing the reading experience as a philological exploration, through the interaction of many different data types, allowing a sophisticated approach to information from multiple perspectives. Even though these tools have been created to empower the reading processes specific of Classical scholars, their application promises new ways of approaching digital content in a much wider context, going beyond the categories of “close reading” and “skimming.”

Translation alignment is a tool that can empower a thoughtful and meaningful approach to reading on digital platforms. But more than that, it can also stimulate a deeper respect for cultural differences. In an increasingly globalized world, translations as means of communicating through cultural contexts and languages are increasingly important: automated translations, as well as interpreters and professional translators, represent a response to a generalized need of fast and broad access to information produced in different cultural contexts. However, being able to access translated content so easily can result in oversimplification, and in the overlooking of cultural complexities. Aligned translations offer an alternative. By discouraging the idea that every word has an exact equivalence, aligned translations add value to the original, rather than subtracting it, through a continuous dialogue between cultural and linguistic systems. Engaging with a translation meaningfully means so much more than merely establishing equivalences: by emphasizing the depth of semantic differences, it can promote better attitudes to cultural diversity and acceptance.