SEAM sees the experiences of teachers, learners, and support staff as multi-threaded facets of shared knowledge environments and thus endeavors to further interweave them. This approach to digital pedagogy is a result of our ongoing collaborative work on the architecture of our first-year survey courses in the Interactive Arts & Science and GAME programs. These courses prepare our students for our third and fourth-year curriculum in which they are expected to collaboratively produce digital media objects, including innovative websites, digital art, and videogames. A notable challenge is using past failures, which tend to be tool-specific, to inform program outcomes, which are high-level objectives (such as learning from one’s successes and failures). Each year, a curriculum committee meets to assess the program outcomes provided as guidance to instructors to refine existing or develop new assignments. The SEAM approach to digital pedagogy outlined below describes how our method for changing infrastructure and assignments in response to our collective past failures continues to evolve. It is intended to keep a record of diverse student experiences while also helping us learn from the inevitable future failures that inform our curriculum development discussions.

We are piloting our SEAM approach to digital pedagogy at three points in a cyclical process during a four-year degree program. First, we equip students with problem-solving and troubleshooting abilities early in their program. Second, examples of critical tool failure in the fourth-year capstone courses circulate between students and instructor in our programs as cautionary tales. Changes in infrastructure, such as the addition of version control servers on campus, are material evidence of responding to failures from yesteryear; however, the narrative of student failure motivates their use. At the third point, once these changes have been made, they are incorporated back into the design of our first-year assignments. In the case of our fourth-year capstone students using version control, it is tempting to view the deployment of a server with version control, a tool, as the solution to a problem. However, paradoxically, the version control server is only a useful tool if it has been used proactively, and consistently, by students. As such, instructing students to use version control in their first assignments (despite its complexity) therefore sets the expectation that they will encounter failure later in the program.

Foregrounding technological failure at the start of our curriculum, we believe, enlivens students’ sensibilities to the creative potential of the tools we teach. Indeed, as Julia Flanders affirms: “The very seamlessness of our interface with technology is precisely what insulates us and deadens our awareness of these tools’ significance” (2019, 292). Having introduced and framed failure as constructive, we intend to map student experiences of failure throughout the program (with particular emphasis on the fourth-year capstone course), and use results gathered from such mapping to continually reflect upon and refine our first-year curriculum over time. Most importantly, we are conceiving of a SEAM approach as a way continually shape and refine the infrastructure in our digital humanities centre in response to changing student needs over time. Our final goal is a structured collection of autobiographical interviews with graduating students; this collection will serve as a knowledge database that we use to improve the learning objectives tied to future course development work. Using a design exercise called user story mapping, in which hypothetical users derive benefits from their actions, we will derive hypothetical case studies from the knowledge base and use them to inform faculty and staff decision-making related to our curriculum. We contribute our method as a working blueprint for collaboration between staff and faculty in the field of digital pedagogy.

Our method aligns itself with the seamful design of networked knowledge outlined by Aaron Mauro, Daniel Powell, and co-authors, who “wish to expose the seams that knit technological infrastructure and academic assessment for both faculty and students working on DH projects” (2017). While our approach concerns itself specifically with the classroom, rather than the context of student research on digital humanities projects discussed by Mauro et al., we equally believe that exposing students to seams—be they the ruptures and fissures that exist when tools break down or the threads that bind their own learning together with that of faculty and staff—empowers them to take an active role in the education as critical users and creators of technology. As Mauro et al. put it, “When we elide the seams between teaching and research, our students become passive agents and mere consumers of education” (2017). By teaching our students object-lessons in instructive failure, we aim to empower them to see digital environments not as spaces that demand rote repetition of established workflows but as creative problem-solving environments in which limitations and constraints can serve a liberating potential.

As the digital humanities continues to establish itself within disciplinary and institutional frameworks, discussions about the state of the field are increasingly turning from small-scale and ad-hoc stories of how different spaces operate to longer narratives about how these spaces continue to change and evolve over extended durations of time. Within this context, our SEAM approach is meant to offer a framework within which digital humanities, broadly, can draw from digital pedagogy, specifically, in order to reflect upon its diverse narratives of institutional establishment, adaptation, and maturation. In what follows, we discuss how we are implementing such an approach in our curriculum. First, we outline our experiences of instructive failure in the context of digital humanities infrastructure. We go on to discuss the design of project-based digital humanities assignments that incorporate instructive failure as a learning outcome. Finally, we conclude by outlining a method for collecting and reflecting upon student experiences of failure over time.

Beyond the Fear of Failure

The instructive value of failure is hardly new to the digital humanities. As John Unsworth reminds us, “Our failures are likely to be far more difficult to recover in the future, and far more valuable for future scholarship and researcher, than those successes” (1997). More recently, Bethany Nowviskie has renewed the value of failure in an age where ruptures in physical research materials prompt reflection upon ongoing institutional reformulations of humanities work; as she writes, “It’s worth reflecting that tensions and fractures and glitches of all sorts reveal opportunity” (2013). In the case of students in our Team-based Practicum in Interactive Media Design and Production, graphical failures were the symptom of an underlying constraint of the tools in hand. Textures in the game had exceeded the memory restrictions in the operating system (the NTFS filesystem defaults to a block size of 4096 bytes), causing a memory overflow that transformed their videogame into a piece of glitch art. A workaround was implemented, and their game debuted shortly thereafter on the packed floor of Toronto’s Design Exchange. How do the lessons learned by these students aggregate into best practices for future students?

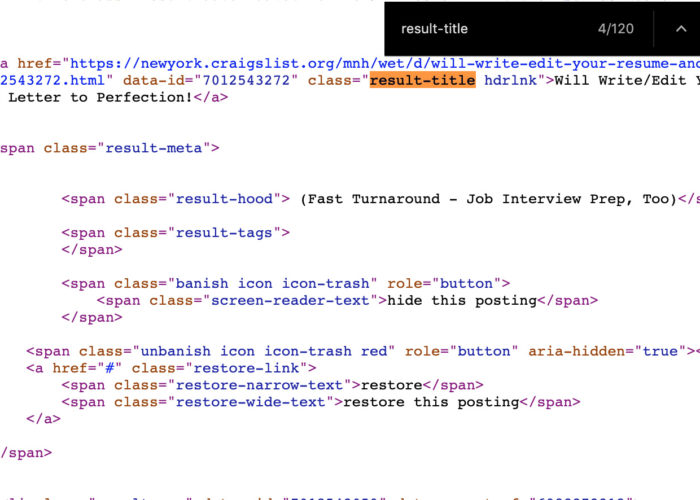

Such glitches, ruptures, and failures often reveal infrastructural constraints in the digital humanities spaces we manage. In the instance of our 2018–2019 fourth-year practicum, the filesystem failure encountered by our students has prompted us to be more aware of the tool constraints for publishing executable games. Furthermore, the public play test was salvageable because of a best practice derived from previous years projects—reverting back to a stable build identified in their revision management system. Prior to that, in 2014, failures encountered by students prompted us to rethink how we scaffold instruction of specific tools, including revision management tools, across an entire curriculum. That year’s students signed up for an off-campus collaborative software development system with integrated version control. Project management services that include git or subversion repositories allow teams to make incremental changes to files in the cloud, syncing updates across all team members as they are made. But our students had encountered a problem: the service, provided under an educational license, did not recognize many of the emails they used as valid institutional addresses and locked them all out of the server. While the problem was resolved, it prompted us to fundamentally rethink how we teach a digital humanities curriculum. The student experiences with version control can also be gleaned from interviews with graduates of the IASC program dating back to 2012. In a similar experience to our 2019 students, graduate Isaac (anonymized) recounts:

About 24 hours before our team was heading to LevelUp to present our game, we encountered a problem where our most up-to-date build of the game was overwritten with an older build, so we lost more than five hours of work. We had to crunch to get our game back to where it needed to be for us to present at LevelUp. This is mainly because of the four lab computers we had access to use for our development, only one of those computers had the [game engine] installed. … We didn’t have a file server. We were using our 2GB free [file hosting service] accounts to share files. We should have had a file back-up system so we could’ve not lost all of that work.

Taking a cue from Miriam Posner (2016), we now administer revision management systems on file servers of our own and deploy assignments that teach students to use them in every year of the program. Like the filesystem failure our students were to encounter in 2019, the version control failure in 2014 prompted us to rethink the operating principles of our digital humanities space. We are continually motivated to formally refine and adapt the student experience in response to failures such as these.

The inevitable failures encountered by our students reveal a problematic underlying much digital humanities work, one that is as wicked as it is productive. In our university-driven work with digital tools and resources, we continually encounter instances in which digital tools developed for industry use don’t neatly align with our academic context. In other words, digital humanities scholars and students frequently work with what Susan Leigh Star and James Griesmeyer call boundary objects, those ubiquitous infrastructural resources which cross between different localized implementations and diverse communities of practice. Working with such objects causes productive failures of all sorts, such as a company’s server not recognizing our student’s institutional email addresses. Elsewhere, we have found that many educational licenses for industry-grade software restrict the contexts in which student work can be exhibited to public audiences. While using such licenses allows students to learn industry-grade tools, it also forces them (and us) to learn about licensing restrictions by diligently avoiding instances in which industry and academic uses for the tool may conflict. Conflicts such as these may tacitly inform many digital approaches to teaching rhetoric and composition that bring industry or for-profit tools into the classroom. To use more ubiquitous examples, using social media platforms such as Twitter or Medium as a venue for publicly disseminating scholarship brushes up against these platforms’ use of text as a vehicle for monetization. What can we learn about the mechanisms of clickbait, bot traffic, or sponsored posts when the tools we use to teach writing are designed to leverage these phenomena? What productive conflicts arise when using YouTube to access Open Educational Resources in the classroom also means students must watch advertisements during a lecture or other class-based exercise? As a variety of digital tools are increasingly incorporated into the classroom, their status as boundary objects that sit across diverse (and at times contradictory) contexts is evident in ways both small and large.

Situating boundary objects such as these in the field of critical infrastructure studies, Alan Liu advocates that digital humanities work “assist in shaping smart, ethical academic infrastructures that not only further normative academic work … but also intelligently transfer some, but not all, values and practices in both directions between higher education and today’s other powerful institutions” (2016). We agree emphatically, and we further believe that such an understanding of infrastructural boundaries forms an approach to digital pedagogy grounded in the instructive value of failure. We continue to learn much from infrastructural failures in which the tool at hand carries and underlying set of constraints that, sooner or later, conflict with the context in which it is being implemented. We further believe such conflicts may be repurposed to suit learning outcomes contingent upon productive failure. For instance, while the research tool Zotero is designed to store bibliographic citations, it can also be used to store other types of information (thus transforming it into a boundary object). Asking students to create a bibliographic record of their classmates’ discussion contributions in Zotero invites failure cases where the metadata students wish to record doesn’t neatly align with the fields dictated by Zotero (and various citation styles); these failure cases prompt students to learn about citation styles and bibliographic records by exploring their limitations and edge-cases. Similarly, much could be learned by asking students to compose a piece of academic writing using a text-based tool that is not designed for outputting print documents. Twine, for example, is designed to create text-based adventure games and interactive narratives; what might students learn about the conventions of academic writing by using Twine to write a short research paper? In our work as digital humanists, we frequently find that the tools we work with aren’t perfectly suited to the task at hand; as such, we have begun to design project-based assignments in which students are deliberately exposed to failures of this sort and taught to learn from them. Whereas digital pedagogy often formulates technological literacy as the ability to use a tool properly, we find technological literacy also encompasses creatively rethinking such practices in inevitable instances when the tool is only moderately suited to the present context. Echoing Mauro et al. and Flanders, this SEAM approach exposes students to the ruptures and fissures inherent in working with digital tools (which we see as boundary objects), rather than suggesting effective digital humanities work involves the seamless operation of technology.

Learning to Fail: Designing Experiential DH Assignments

The idea of a digital pedagogy based in productive failure first emerged through a conversation between Alex Christie and CDH Project Coordinator and Technical Assistant, Justin Howe. Undertaking a rapid prototyping process of our digital prototyping assignments, they considered assigning Axure RP (a digital prototyping tool) as an environment for developing small-scale persuasive games. (Bogost 2010) They agreed that the fact Axure is not a game development environment was precisely why this assignment would be so valuable to our students—the lesson to be learned was that success always means success within a set of allotted constraints. In this way, the Axure tool was being deliberately used in a context for which it was not intended—creating videogame prototypes—and therefore explicitly deployed as a boundary object. The assignment therefore forced students to figure out what creative ideas could be successfully implemented within the constraints of the Axure RP prototyping environment and other assignment parameters. In this way, it sought to expose students early on to the pragmatic value of digital prototyping (and digital humanities work broadly), not solely as an exercise in dreaming up blue sky potential, but also—more unforgivingly—as a process of forging the realistic out of the fantastic. They were bound to encounter productive failure.

If the chief learning outcome of the assignment is for students to understand that concept cannot feasibly exist apart from execution, it also codifies the underlying pedagogical values within which we situate our pedagogy. The prototyping work asked of students requires them to approach Axure as a creative problem-solving environment. This means students frequently encounters instances when the tool does not allow them to achieve an important part of their intended game. In order to move forward, students must fundamentally rethink how the tool can be used in order to achieve their stated outcome. For instance, one team created their own method for causing screen brightness to dim by overlaying a black square on the window and tying its opacity to a variable whose value was influenced by player actions. Another team failed at creating a collision-detection system that would stop the player from going through the walls of a maze; instead, they used Axure’s condition builder to ensure the two objects could never overlap. By asking students to create a videogame with a tool moderately suited to the task at hand, we build an environment where students quickly reach the constraints of the technology they use. This creates an experiential learning opportunity in which students are forced to encounter and learn from moments when technologies do not work as intended, learning to create new solutions to problems when a previous approach has failed. A key learning outcome of the assignment, then, is not so much learning how to use the assigned tool correctly as much as it is learning to continue using the tool to productive ends when it fails and breaks down.

Such a learning outcome requires students to learn to see the software environment used not as a space where outcomes are met by replicating established workflows (or a sort of digital reimagining of Paulo Freire’s banking model of education) but instead as a system that can be creatively rethought and repurposed. Central to this view is an emphasis on project management and collaboration fundamentals, which are built right into the architecture of the assignment. Following the CDH’s decision to host its own server infrastructure in 2014, we decided to build subversion into the architecture of the assignment as well. Each team is allocated its own SVN repository, and each repository is then used for students to collaboratively work on their version-controlled Axure project. Teams are also asked to communicate using Discord, and Andrew Roth uses web hooks to push changes to the subversion repository directly to each team’s corresponding Discord. Asking teams to construct their prototype using a version-controlled workflow teaches practical lessons in project management, such as using a centralized repository rather than emailing files and letting team members know when new deliverables are added. These are key lessons learned from previous instantiations of our fourth-year practicum, which we have now rolled forward into the design of our first-year assignments.

Most importantly, asking students to adopt version-control and team communication solutions as part of their assignment workflow means designing a particular lesson into the assignment: that collaboration is about accountability. Before beginning their prototyping work in earnest, teams are required to submit a Developer Document that divides prototyping work into five roles (Visual Designer, Data Modeler, UX Designer, UI Designer, and Creative Director) and asks teams to outline how the deliverables for one role required assets produced by another. This division of assignment duties foreshadows the communication challenges of the fourth-year teams; Victor (anonymized), class of 2016, said his experience of failure manifested “by either conveying too little information, outdated information, or undecided information across team before it [was] vetted.” Teams quickly learn that certain parts of the project cannot be completed until its dependencies are ready, which means that various teams encounter workflow and communication failures that expose gaps in their existing conception of how collaborative work gets done. In their final presentations to the class, numerous first-year teams reflected upon the importance of coming together to work as a team, whether such reflection included successful team workflows or admitting that a siloed approach had not delivered the expected results. We find using formalized systems, such as Discord and SVN, for team-based work helps students identify and visualize interpersonal and communication errors because team progress becomes directly contingent upon students using the system to send updates to fellow teammates. Giving students low-stakes environments to learn from such failures early in the program prepares them to address, or even obviate, high-stakes failures of this sort in their upper-year team-based practicum.

The lesson that workflow is as much about accountability as it is about cultivating a positive interpersonal environment is one that can only be learned experientially, which means designing a pedagogical framework within which teams can safely encounter workflow failures and move forward based on insights discovered therein. This framework prepares students to learn from team-based failure in two ways. First, in the weeks leading up to the final assignment, the instructor delivers lectures on topics including digital prototyping fundamentals and team management, which explicitly outline the different stages of team formation and best practices as teams move from one stage to the next. Second, the incorporation of technologies such as SVN and Discord creates a collaborative environment in which output and accountability are directly fused: each time a student works with a new version of the project, they cannot begin their work until encountering the latest revision made by another team member. Similarly, if the team hits a roadblock in their prototype because a certain asset or dependency is missing, the entire team can immediately identify the source of accountability. Both conceptually and pragmatically, then, the assignment is framed as an exercise in developing competencies in collaborative prototyping, defined as an iterative process where progress comes from finding out what doesn’t work and then moving forward. In this way, collaboration failures experienced by teams serve as object lessons in scope management, in which students are forced to consistently ask which practices best suit their goals and which do not. These project-based assignments therefore function as experiential learning opportunities in which students learn from technological and collaboration failures by directly encountering and overcoming them. So far, results have exceeded expectations. One team made a game in which navigating the maze of Brock’s Mackenzie Chown complex served as a functional metaphor for navigating depression. Another made a game about surveillance and counterinsurgency, while still others tackled topics including personality disorders and cultivating gratitude.

The first stage of our SEAM approach to digital pedagogy thus involves designing project-based assignments where students reach their own insights into doing digital humanities work by learning from instructive failure. Such failures are built into the assignment by treating the tools being taught as boundary objects, or technologies that are not perfectly suited to the given task. These assignments prompt students to reach the limitations of the tool and creatively overcome them. In the context of videogame design, this may include using a non-Game Development Environment (such as Axure) to create a videogame; in still other educational contexts, this may include using a Game Development Environment (such as Twine or Game Maker) to write a research paper or using a monetized platform (like YouTube or Facebook) to disseminate Open Educational Resources. In this way, a SEAM approach to designing digital humanities assignments focuses more on the assembly of conceptual and technical systems within which we ask students to explore and create, rather than handing down prescribed workflows by rote (again, with a nod to Freire). In turn, we ourselves refine such systems in response to student experiences later in the program, incorporating tools such as SVN and encouraging students to encounter the places where their work using such tools may begin to show at the seams.

Learning from Failure: Student Reflection through Data Visualization

In order to prompt student reflection upon failures encountered in their project-based work, we visualize student data generated throughout the course of these projects to build models of student knowledge. Andrew Roth creates such visualizations by taking the Subversion history from each team and visualizing it with Gource, an open source tool created by Andrew Caudwell that displays file systems as an animated tree evolving over time. Visualizing the complexity of the shared file system under version control at once makes the metadata of the process more legible and the task of growing that system more daunting. For example, by visualizing and comparing each repository of a single class, we can see at a glance which teams closely emulate the instructor’s example project and which grew beyond in the allotted time. While the rules of collaboration require students to diligently maintain the up-to-date version of their project, or head, by checking in functioning code, the metadata captured in the history shows a record of every failure including malfunctioning ignore files, desktop shortcuts mistakenly checked in as assets, and abandoned plugin folders. In sum, the Gource visualization for each team shows how that team’s version-controlled files and folders changed throughout the course of the project, providing a visual rendering of student activity in Axure. The visualizations open a space for reflecting on both the metadata borne of the technological infrastructure required for collaborative project work and the narrative that emerges from managing the project’s complexity over time.

For example, in both visualizations the sample project created by the instructor is created first, followed by each group project. In an instant we can see there are sprints of productivity during lab times and very few team members committing to projects on the weekends. Using the instructor sample as a measuring stick, we can see that there are few projects in the 1F01 class that emulate the sample project’s complexity, whereas the 1P04 course has a smaller sample project and larger, more complex group projects.

We have also used Gource to visualize the videogames created by our fourth-year students. Using data from each SVN repository used over the past four years, we are able to see differences between each of our past four student teams. For instance, the first group using version control (before hosting a server on premise) demonstrates a tightly controlled structure managed by only one or two users. In subsequent years, the number of total simultaneous users increases. This suggests the repository is used by more individuals across their respective teams, which is supported by the push by faculty to use version control across all years of the program. The number of large-scale changes over time (such as branches or deletions) also increases in frequency which indicates that mistakes are made, large scale changes are applied (such as telling subversion to ignore certain file types), and these mistakes are corrected as time passes. It is also clear how the scope of the single 4L00 project dwarfs the first-year projects in size and complexity.

After presenting these findings from our first round of visualizations at the 2018 Digital Pedagogy Institute, we began integrating these visualizations back into the pedagogical structure of our first-year classes. Once teams have completed their prototypes, we provide them with the Gource visualizations of their work as an .mp4 video and use these videos as prompts for their final reflective assignments. In their reflective essays, students frequently noticed that work was conducted ad-hoc by different team members, rather than following a pre-established working schedule. Gource videos frequently showed irregular bursts of activity from different team members, rather than steady and predictable output that followed a coordinated project schedule. This was also one of the key ways in which Gource visualizations of work done in our first-year courses differed from that of our fourth-year courses. As such, students frequently remarked that a key failure was not coordinating their schedules and efforts more closely, and that such failure was not apparent to them until they saw the timeline of their Axure work rendered visually through Gource. Using formalized systems for student collaboration lets instructors visualize student activity and provide such visualizations as tools for student reflection; we find SVN and Gource to be an effective combination of tools for designing these reflective exercises.

While the principal outcomes of the assignment are for students to assess their evolving abilities in collaborative environments, the incorporation of the Gource visualizations further demonstrates for students that soft skills including communication, organization, and team dynamics cannot and should not be neatly parsed from technical considerations such as scheduling deliverables, maintaining project dependencies, and designing data and folder structures. The assignment furthermore reframes data visualization techniques not simply as tools for revealing objective facts but additionally as environments for metacognitive reflection and personal growth. How might digital tools reveal the seams between a student’s own approaches to collaboration and those of their teammates? As we prompt students to derive reflective insights from data visualizations of their work, we also encourage more technically-minded and tech-averse students to understand that technical implementation and interpersonal interaction co-construct the latticework upon which their knowledge matures and thrives.

Stitching Our Work Together: Faculty and Staff Reflection through Autobiography Mapping

Together, our use of digital prototyping assignments and reflective exercises involve stitching together disparate strands of student failure and digital tools, using such threads as opportunities for both student and instructor learning. Thus far, we have reached a series of findings for designing project-based digital humanities assignments and using them as a vehicle for faculty and staff reflection. First, it is essential to deliver lectures on team formation fundamentals as part of the introduction to project-based assignments; doing so both introduces students to collaboration best practices (a core element of doing digital humanities work) and teaches them how to move forward from inevitable stumbling blocks. Instructors can further encourage students to learn from failure by discussing the fundamentals of scope management, time management, and rapid prototyping—all of which assume that ideas are developed by encountering errors in planning and then retooling that plan in order to move ahead. Doing this over and over, or learning through iteration, dispels the common myth that excellent ideas and strong skill sets emerge from a vacuum. As part of this approach, instructors can introduce the assignment by giving students a template and encouraging them to tweak it; for instance, our GAME students are given a short game prototype made in Axure RP and asked to fix a series of bugs (thereby preparing them to fix the eventual errors in their own game prototypes). Most of all, faculty and staff can and should work together to design the suite of technical dependencies for the assignment, architecting an environment that encourages students to safely explore and experiment instead of copying prescribed workflows by rote. While staff provide insight into the technologies available for classroom use (in our instance, Andrew facilitates the integration of Axure with SVN and Gource), instructors design activities and assignments where these technologies are used to create materials they were not primarily designed to output (and share the results with staff administering the tools). Such collaboration allows for staff and faculty to approach the classroom as an environment for low-stakes failure, while continuing to prioritize student learning as the setting’s principal outcome.

As we continue to move forward based on these insights, we are considering how this form of faculty-staff collaboration can scale up from the level of the individual course. The final stage of our SEAM approach does just this, examining student progress longitudinally throughout the whole of the program and over the course of multiple years. Inspired by Donna Haraway’s formulation of cyborg subjectivities, this next stage of our work sees student autobiographies as reflexive records of where intersectional identities evolve alongside, and are imbricated with, the technologies with which they work. This research will analyze longitudinal student experiences through user story mapping, a technique commonly used to define priorities within agile software development. Software developers lead interviews and focus groups to understand how users’ expectations map to the offerings of their software. The scope of the user story mapping in software development is deliberately broad and shallow, narrowing the most possible use cases into minimum viable product releases. In order to catch the broadest perspective on student experience, we have chosen biographical information that demonstrates the student’s relationship to technology—their technobiography. The technobiographical method originally loosely outlined by Kennedy in 2003 has previously been applied to stories of learning by youth (Brushwood-Rose 2006) and educators (Ching and Vigdor 2005). By collecting, transcribing, and tagging biographical interviews, we intend to create a repository of user stories that can be drawn upon to help address infrastructure challenges holistically. The result will be a dynamic and searchable repository of student reflections on their learning experience that faculty and staff can consult in order to inform various levels of decision-making. As the repository grows over time, it will allow additional insight into how student learning in our digital humanities curriculum changes longitudinally. While the idea of a “minimum viable product” seems inherently reductionist, the goal is not to produce static or artificial boundaries around the learning experience, rather to set priorities and outline critical paths to completion relative to external factors (e.g., time, money, space, goodwill). Our students’ narratives tell us as much about the subjectivities that move through our learning systems as they reframe the systems-level formulations to which infrastructure, by necessity, reduces human experience.

Scaffolding upon the reflective assignments introduced alongside Gource visualizations of student work, we intend to collect student autobiographies as they move throughout the program and across multiple years. This will result in a searchable database of key challenges and successes encountered by student teams over time, revealing key inflection points in the development of our infrastructure and our curriculum (such as our 2014 failures associated with version control and our 2019 failures with the NTFS filesystem). As we continue with this work and gather findings over multiple years, we envision our method and the data it generates as an autobiography of long-term growth and adaptation in Brock University’s Centre for Digital Humanities. While digital humanities spaces continue to disseminate news of progress and successes, we believe they can also share key failures as part of a productive and forward-looking institutional narrative. What are the stories behind the technologies and best practices incorporated into our labs and our curriculum? How might student experiences of technological failure inform decision-making processes when it comes time to purchase new workstations, format hard drives, and set up server space for student work? Through their own stories about themselves and how they change over time, our students and their experiences of failure may reveal much of ourselves—our intellectual values, our operating principles, and what we may still become.