The Paxton Massacre

In December 1763, following years of backcountry warfare, a mob of settlers in the Paxton Township—just outside what is today Harrisburg—murdered twenty unarmed Conestoga Indians along the Pennsylvania frontier. Soon after, hundreds of these “Paxton Boys” marched on Philadelphia to menace a group of Moravian Indians who had, in response to the violence, been placed under government protection. Although the confrontation was diffused through the diplomacy of Benjamin Franklin, the incident ventilated long-festering religious and ethnic grievances, pitting the colony’s German and Scots-Irish Presbyterian frontiersmen against Philadelphia’s English Quakers and their Susquehannock trading partners.

Supporters and critics of the Paxton Boys spent the next year battling in print: the resulting public debate constituted one-fifth of the Pennsylvania’s printed material in 1764 (Olson 1999, 31). Pamphlets, which were inexpensive and quick to produce, were the medium of choice—hence the debate is often called the Paxton pamphlet war. But many other printed and unprinted materials circulated simultaneously, including broadsides, political cartoons, letters, diaries, and treaty minutes. Although this debate was ostensibly about the conduct of the Paxton vigilantes, it quickly migrated to other issues facing colonial Pennsylvania, including suspicions of native others, anxieties about porous borders, a yawning divide between urban and rural populations, and the proliferation of what we might today call “fake news.”

While most researchers explore the pamphlet war through John Raine Dunbar’s scholarly edition, The Paxton Papers (1957), much of the debate cannot be found in Dunbar’s edition.[1] There are dozens of alternate editions, answers, and responses to the pamphlets identified by Dunbar, and, if one examines the originals, one uncovers engravings, artworks, and other forms of materiality that could not be examined through textual transcriptions alone. Perhaps most importantly, the current approach to the Paxton debate, which prioritizes printed materials—namely pamphlets, broadsides, and political cartoons— inadvertently reinforces colonial and cosmopolitan biases. That is, much of the Paxton debate happened outside Philadelphia printers. If researchers are to reckon with the massacre’s geographic, ethnic, and class complexities, they ought to consider manuscript collections that give voice to backcountry settlers and the indigenous peoples at the center of this tragic episode.

Digital Paxton

Digital Paxton seeks to expand awareness of and access to such heterogeneous records. The project began as a digital collection of pamphlets available through the Library Company of Philadelphia and Historical Society of Pennsylvania. As partners in the project, those institutions are responsible for digitizing at their own expense more than half of the records available in Digital Paxton. Subsequent partnerships have brought scans of contemporaneous Pennsylvania Gazette issues at the American Antiquarian Society; Friendly Association correspondence from the Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections; letters from the John Elder and Timothy Horsfield Papers at the American Philosophical Society; and congregational diaries from the Moravian Archives of Bethlehem. Each expansion has underscored that the 1764 pamphlet war included much more than pamphlets.[2]

As important as the diversity of materials is the structure of the collection. The design of online publishing platform Scalar encourages researchers to draw connections between and across collections. Specifically, Scalar’s flat ontology enables all objects (images, transcriptions, sequences of images) to occupy the same hierarchy: no object is more of a subject than another object. In practical terms, this means that researchers encounter Governor Penn’s letters in the same pathway as they do letters between Quaker leaders and native partners, accounts of diplomatic conferences, and the writings of Wyalusing leaders. At a technical level, then, the platform supports the philosophical goals articulated by the editors of the Yale Indian Papers Project: the digital collection as a common pot, a “shared history, a kind of communal liminal space, neither solely Euro-American nor completely Native” (Grant-Costa, Glaza, and Sletcher 2012, 2). This is the allure of the digital edition: when thoughtfully structured, digital editions better accommodate a constellation of material forms, voices, and perspectives than traditional print editions.

Although Digital Paxton is foremost a digital collection, the project includes a scholarly apparatus similar to Dunbar’s Paxton Papers. However, whereas Dunbar’s introduction is singular and possesses the patina of definitiveness, this project is multi-authored, interdisciplinary, and less didactic. Practically speaking, each of the project’s twelve historical overviews, lesson plans, and conceptual keyword essays serve as freestanding entry points to the digital collection. That is, if a history student were interested in Conestoga Indiantown, she might choose to read Darvin Martin’s essay, “A History of Conestoga Indiantown,” use its links to explore the digital collection, and perform additional research using the various linked resources listed below further reading. Or, if a literature student wanted to think more carefully about what “elites” meant in the eighteenth-century, she might begin with Scott Paul Gordon’s essay, “Elites.”

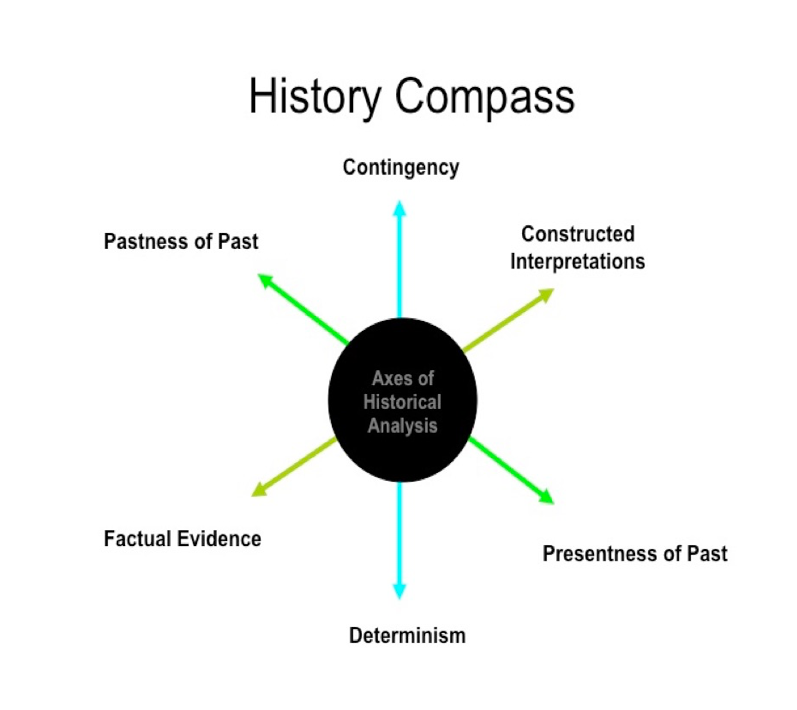

Students may use the project’s introduction or interpretative pathways to traverse the project; however, rather than promoting a singular, definitive approach to the massacre and pamphlet war, Digital Paxton embraces what Adele Perry (2005) and others have called polyvocality. By layering materials and contexts, each is made less definitive, more partial, contingent, and subject to scrutiny. This approach guards against rote thinking: the Paxton massacre is a story of genocidal violence and indigenous dispossession, but it is also a story of identity politics, self-governance, resistance, and active peace-making.

As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie argued in a famous TED talk, narrative multiplicity acknowledges the complexity and dignity of human experience. “Stories matter. Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity,” explained Adichie. “[W]hen we reject the single story, when we realize that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise” (Adichie 2009). While regaining paradise is well beyond the scope of this project, grappling with the complexities, erasures, and ambiguities of historical memory falls within its purview, thanks to the generous contributions of scholarly and archival collaborators.

Collaboration and Acknowledgement

Given that Digital Paxton is very much a bootstrap operation—cobbled together without any significant external funding—recognition of labor is the least that can be offered collaborators. To this point, the first two points of the “Collaborators’ Bill of Rights” have informed the project’s approach to collaboration and acknowledgement:

1) All kinds of work on a project are equally deserving of credit (though the amount of work and expression of credit may differ). And all collaborators should be empowered to take credit for their work.

2a) Descriptive Papers & Project reports: Anyone who collaborated on the project should be listed as author in a fair ordering based on emerging community conventions.

2b) Websites: There should be a prominent ‘credits’ link on the main page with primary investigators (PIs) or project leads listed first. This should include current staff as well as past staff with their dates of employment (Clement, Croxall, et al. 2011).

Digital Paxton is the fruition—however nascent—of contributions from dozens of archivists, curators, scholars, and technologists, whose labor is subsidized by archives, cultural institutions, research libraries, and universities. Although this project was sparked by personal research interests, little would be available today without the resources, labor, and expertise of those individuals and institutions. Acknowledgement, on the project’s Credits page and in the publications and talks, is one form of (admittedly paltry) recompense.

Collaborators take many forms, and there is perhaps no cohort more vital to this project’s future—and that of the humanities more broadly—than that of student-collaborators. This project embraces Mark Sample’s notion of “collaborative construction,” through which students produce new knowledge in concert with one another, their professor, and the project, broadly conceived. “A key point of collaborative construction is that the students are not merely making something for themselves or their professor,” explains Sample. “They are making it for each other, and in the best scenarios, for the outside world” (Sample 2011).

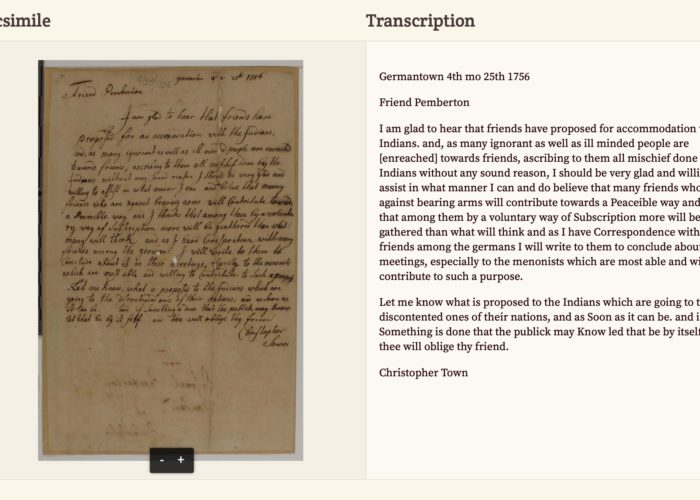

The second half of this article seeks to put this philosophy into practice using a case study. In the spring 2017, two faculty members, Benjamin Bankhurst (Shepherd University) and Kyle Roberts (Loyola University Chicago), who were co-teaching an undergraduate history course, “Digitizing the American Revolution,” sought to introduce students to digital humanities tools and methods. They opted to create an assignment through which students would learn to transcribe eighteenth-century letters using scanned manuscript materials from Digital Paxton. Each student was responsible for transcribing a page of manuscript. After Bankhurst or Roberts vetted students’ work, transcriptions were loaded into Digital Paxton, with a credit to each student-transcriber.[3]

The project was successful on several accounts. First, it expanded the number of transcribed (and searchable) resources in Digital Paxton. Second, it required teaching materials that can be repurposed in future transcription assignments. And third, it attracted a new community of researchers to the site. This interest is certainly measurable in the students who participated in the assignment, many of whom now regularly share Digital Paxton updates on social media platforms. Perhaps most importantly, Roberts’s graduate students—Kate Johnson, Marie Pellissier, and Kelly Schmidt—took ownership of the project in ways that made it both more effective and more scalable. Using their experience within the classroom and reviews of transcription pedagogy best practices, they offered recommendations on how to modify the Digital Paxton site to facilitate easier transcription, created documents guiding students through some of the hurdles in the transcription process, and offered feedback on improving the exercise as a classroom assignment. Johnson and Schmidt will now describe their experience with the transcription project, and the challenges and opportunities it provided.

A Case Study in Digital Pedagogy

As members of Roberts’s class, we were asked to transcribe a page from Digital Paxton’s digital collection. We enjoyed the process of learning how to identify and transcribe unfamiliar eighteenth-century characters consistently, as well as the sense that we were contributing to a larger project of significant historical value to scholars and the general public. However, along with our undergraduate classmates, we encountered challenges as we struggled to interpret the manuscripts. We felt that we could help expand the project by creating a guide for people planning to transcribe individually or in a crowdsourced or classroom setting.

The assignment began with an introduction to Digital Paxton from its creator, Will Fenton (via Skype). As a class we explored the site together and received a contextual overview of the Paxton pamphlet war. The contextual information helped us better understand the significance of our assignment in relation both to our course and to the work of historians more broadly. Moreover, the personal touch of talking to the website’s creator cultivated greater interest in the project.

The directions for the assignment were simple: transcribe one page assigned from the Friendly Association manuscripts (Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections) and write a three-paragraph essay about what the page contained, whose voice it was written in, and who it excluded, and how it felt to participate in this transcription process as a historian. Students did not use any transcription aids. We each viewed the manuscript page in a web browser (or printed it out), then typed transcriptions using a word processor. However, these seemingly simple directions proved more complicated to students who were uncertain how to format their transcription consistently or account for peculiar eighteenth-century abbreviations. Some students opted to peer-review one another’s assignments before turning them in, which helped improve consistency and their understanding of the materials with which they were working.

For some students, the public nature of the transcription increased their commitment to the assignment. In her essay on “Teaching the Digital Caribbean,” Kelly Baker Josephs discusses how adding the public as an audience for coursework creates a “performance” aspect that changes the course experience (Josephs 2018). We saw this with our class, as several students put more time and effort into the assignment, such as peer reviewing each others transcriptions, expressly because it would be shared publicly on a website.

Student Responses

Each student turned in a short essay detailing the content of their transcription, its biases, and their experience transcribing it. In addition, we had a class discussion on the greatest challenges in transcribing and practices that might improve the transcription process and make the final product more useful. One student, who described working with the source as both “tedious and exciting,” encapsulated the gist of most anonymous student responses to the assignment.[4] The most frequent obstacles identified were difficulty reading the handwriting, deciphering inconsistent capitalization and spelling, differentiating between vowels as well as lowercase “L’s” and “F’s,” and unfamiliarity with the long “S.” While the scans were clear, some students had trouble reading their assigned text because authors often used both sides of the page, the ink bleeding through from one side to the other. One student suggested that reading the text and then rereading it before transcribing made it easier to understand the content. Others said that they needed more knowledge not only of paleography and period syntax, but also context about the history of the time period, region, and specific event in which these papers were situated. Without such broader knowledge, students sometimes struggled to transcribe local place names, like “Minisinks,” and the names of subjects in the documents, especially Native Americans, such as “Scarroyada.”

Nevertheless, many of the same students who struggled to decipher the eighteenth-century English and handwriting still expressed an appreciation for, and a better understanding of, the work of historians. One student wrote, “I’m quite honored and impressed that I had the opportunity to participate in the understanding and detailing of history, especially in the turn of the Revolution.” Several others professed a “newfound respect for historians” and claimed that they felt like they were “doing the work of a real historian.”

Most of the students were not history majors, and for many, this was the first time they had engaged with primary sources. Most of their previous coursework in history had focused on secondary source readings about big ideas and events, which students assessed through essay-writing assignments. One respondent noted that, “working with primary sources feels much more immersive and enlightening, in terms of being able to see a glimpse of what their life was like and the issues they dealt with in their time.”

While the process of transcribing manuscripts was monotonous, students said that work with handwritten letters changed the way they engaged with materials. One student said, “It felt good to work with a primary source such as this letter, and be able to see the firsthand view of the writer and a glimpse of their world.” Several students also welcomed access to Native American voices, who are often silenced in settlement narratives. This recognition encouraged them to grapple with the possibility that some of these documents may not have been telling the whole truth about the event. One student even mused that soon historians might have to decipher audio sources rather than interpret handwriting.

These student responses align with pedagogical scholarship. Notably, William Kashatus posits that close analysis of primary sources gives students a more personal understanding of history. Because primary sources can “evoke emotional responses,” students are better able to “identify with the human factor in history, including the risks, frailties, courage, and contradictions of those who shaped the past” (2002, 7). According to Kashatus, students are better able to recognize the biases in historical records and assess their own contemporary biases, and those of modern-day media, when they have engaged with close-readings of historical sources in the classroom (2002, 7–8). Student feedback from our classroom assignment reflects that students felt they gained a sense of intimacy with historical writers. Avishag Reisman and Sam Wineburg, writing about the new common core standards, have argued that working with primary source materials challenges students to think carefully about what does and does not count as evidence. Reisman and Wineburg argue that primary source materials compel students to “interrogate the reliability and truth claims” rather than to simply “cull” evidence (2012, 25-26). Through transcription work, students must read the text word-for-word, compelling them to think more critically about what is being expressed and not to take a document’s message at face value.

Gathering Survey Data

Although the students’ comments were helpful, we realized we needed more feedback before we pursued any future crowdsourced transcription projects. To that end, we administered an anonymous one-page survey to the participants of a transcribe-a-thon event at Loyola organized by the Center for Textual Studies and Digital Humanities in conjunction with a nationwide event. Approximately 70 students, staff, and faculty attended, 43 of whom elected to complete the survey. Additionally, we administered the survey to 21 students enrolled in a 100-level “Interpreting Literature” class. For the transcribe-a-thon, participants used a subscription-based transcription program called FromThePage.

The survey consisted of nine total questions, with six multiple choice and three open-ended questions. Questions solicited feedback on the ease of participants’ use of the transcription program and the experience of transcribing itself. Two questions asked about the participants’ perceived value of the experience of transcribing. At the end, participants were asked to provide an email if interested in future transcription projects. The anonymous survey results highlighted what elements of transcription work most engaged participants and what challenges or barriers thwarted their participation. Thus, the survey offered concrete data to support ideas that emerged from student feedback in the Loyola/Shepherd assignment. From these conclusions we gained insights into what would make a successful transcription project for interacting with digitized early American documents, and those insights informed the guides we created for Digital Paxton.

One key difference was experiential: students preferred the communal work of a transcribe-a-thon to the solitary work of a for-credit assignment. While the majority of both sets of students said that they found the experience valuable, more transcribe-a-thon participants recorded satisfaction. Additionally, a much higher percentage of transcribe-a-thon participants expressed interest in future transcription projects (82% of event participants compared to 38% of classroom participants).

We evaluated these discrepancies using responses to the open-ended questions, which included a question about what was the most valuable part of the experience. The classroom included some but not all of the additional contextualizing elements that were included in the event, such as the talks and recitations of historical speeches and songs. These elements, combined with the celebratory atmosphere of the event (held as a birthday celebration for Frederick Douglass), helped to affirm the sense that participants were both learning and contributing to a living project. The survey results and our experience with the transcribe-a-thon show us that transcription projects not only get students working with primary materials, contributing to scholarly work, and learning to use digital tools, but they also inspire students to participate in future projects.

Translating Feedback into Practice

Student feedback and survey responses provided some clear takeaways for Digital Paxton. Although incorporating a transcription project into a class’s curriculum and awarding class credit and public access incentivized students’ contributions, assignments needed to be structured to foreground both historical and logistical context for transcriptions. Additionally, assignments needed to emphasize the importance of student transcriptions to the long-term goals of the project. When we began contributing transcriptions to Digital Paxton, the project did not have guidelines for transcriptions or a built-in transcription platform.

We developed a “Transcription Best Practices” guide for Digital Paxton, now available in both the Transcription and Pedagogy sections of the site for educators who want to introduce similar assignments in their classrooms. In it, we attempted to anticipate contextual questions that might arise during an assignment. We used the feedback from the Loyola/Shepherd assignment to pinpoint the most important contextual clues needed. We included images of eighteenth century writing conventions, such as the elongated “s” and the shortening of common words like “which” to “w/ch.”By equipping potential transcribers with the materials they need to understand the papers in their historical and cultural context—the guidelines, site introduction, and historical overviews—we met a need expressed in our survey results.

Digital Paxton’s overview of the conflict provides contexts for an event with which students are only vaguely familiar, but it does not necessarily supply students with definitive answers. Students build intimacy with the text by describing it, having to assess as they go along the choice of language and style used. Writing out the text seemed to improve students’ reading comprehension. By adding transcription guidelines, we further sought to help students avoid getting bogged down by the complication of language or handwriting. In their response essays, students use the text they transcribed as “evidence” about where the author stood ideologically within the conflict and how the conflict unfolded. As one student described, the source was a piece to their understanding of the larger puzzle.

Selecting a platform and developing a process through which future cohorts could contribute to the project were more complicated. After all, our approach—toggling between a web browser and word processor—would not work well for larger classes or transcription projects. We had three key stipulations for a prospective transcription platform: it had to be easily accessible to and usable for transcribers, well-supported, and interoperable with Scalar. We identified two platforms that met most of our requirements: Scripto and FromThePage. Both enabled users to record transcriptions alongside scanned pages, a priority, for students in the “Digitizing the Revolution” course. Scripto offered a free, open-source transcription tool, but it was not being fully supported by the developers, and we did not know if it would continue to be supported in the future. Moreover, Scripto required scanned pages to be migrated from Scalar to Omeka. We selected FromThePage because it was well-supported, did not require an Omeka installation, and Fenton could use his university library’s subscription (Fordham University).

On a logistical side, the survey responses also helped us understand the barriers to using online transcription tools. The most prevalent issue was readability of the scanned text, followed by challenges navigating the transcription platform. While there are limitations to how much can be done to address manuscript readability, especially when it comes to eighteenth-century manuscript material, we took the latter concern into account when we created “Using FromThePage.” In that documentation we sought to create clear, concise instructions on how to use FromThePage in conjunction with Digital Paxton. This effort included screenshots illustrating how to register as a user and how to locate pages available for transcribing, a key issue for participants at the transcribe-a-thon. By anticipating user experience issues, we hope to enable students to lose themselves in the rich texts and contexts on Digital Paxton, rather than spend valuable time and energy troubleshooting the mechanics of the process.

Future Collaborations

While our experiment in student manuscript transcription was not without its limitations, the process of pursuing student involvement and recording student feedback have made Digital Paxton a more effective teaching tool. Thanks to the labors of Kate Johnson, Kelly Schmidt, and Marie Pellissier, the project now includes best practices for transcribing eighteenth-century manuscripts (Transcription Best Practices), an assignment for integrating a similar exercise into a university classroom (Transcription Assignment), and a platform through which any educator may bring Friendly Association manuscripts into her classroom (Transcriptions).

From our research and practical experience, we have found that transcription of primary sources encourages students to read texts more closely, to view writers as human beings (rather than detached historical figures), to confront archival gaps, silences, and erasures, and to view their work as contributory to a collaborative project. In her recent post at the National Archives, Meredith Doviak wrote that with increased digital access to collections, students now have more opportunity to become “active critics and curators of those literary productions rather than mere explicators of them” (2017). Transcription projects can serve as vehicles through which students act as participants in knowledge creation, honing valuable critical thinking skills and a historically-informed sense of media literacy that will serve them well inside and outside the classroom.