Introduction

This article is an experimental effort to add a new dimension to the priority of reflection, which characterizes the crafting of both print and ePortfolios (see Yancey 2009; Bourelle, et al. 2015: the concept of rhetorical velocity). Rhetorical velocity (Ridolfo and DeVoss 2009; Ridolfo and Rife 2011) refers to how reusable texts are in acts of circulation and recomposition. Media boilerplate texts represent an exemplar genre of texts predicated on maximizing rhetorical velocity because these texts are designed to populate multiple contexts and to be easily resituated. The application of a heuristic based on rhetorical velocity acts of reflection can take the form of close-readings of ePortfolios by students or instructors. However, in this article, I will outline a computational approach to measuring rhetorical velocity of ePortfolio textual content, visualizing findings, and using these findings to assist reflection and refinement of ePortfolios. This computational approach revolves around a Python “bot” script with the portmanteau RePort_Bot (Report + ePortfolio + Bot). The RePort_Bot crawls web pages, scrapes textual content and metadata such as page titles, analyzes the ePortfolio, and returns results to users in the form of descriptive statistics and visualizations.

Robot Rationale

The RePort_Bot (and its emphasis on rhetorical velocity) is galvanized by two related theoretical questions: how does the digital nature of ePortfolios affect composing and reflection practices and how can we leverage the digital affordances of ePortfolios in the service of better writing and design?

One obvious difference that the digital nature of ePortfolios makes manifest is the ability to incorporate diverse content as a showcase of skills, experiences, and knowledge-bases. This includes hyperlinking to resources or hosting a range of media such as PowerPoint presentations, YouTube videos, audio tracks (Yancey 2013, 26–27; Rice 2013, 42), and social media content (Klein 2013). Reynolds and Davis (2014) also observe that ePortfolios represent dynamic means of storing and displaying work (Kilbane & Milman 2003, 8–9). With the expanded technical avenues that ePortfolios bring to writers comes the corresponding obligations to manage ePortfolio content and plan for its live deployment (Barrett 2000, 1111).

While not solely targeting ePortfolios (although ePortfolio assignments do factor heavily into her theorizing), Silver (2016) offers a handy gloss of what the digital (hyperlinking, video and audio sharing, social networking) means for the act of reflection in the writing classroom. To paraphrase Silver (2016, 167), reflection with and through digital media platforms becomes easier and more enjoyable as an activity, fosters collaboration and dialogue among peers, becomes more visible and measurable (167), and enables students to enter into more robust self-dialogues, thereby increasing their awareness of their own rhetorical actions and their ability to self-correct (Silver 2016, 169). Silver cites Meloni (2009) on the use of GoogleDocs revision history to provide automatic feedback to students on the trajectory of their writing, which then led to more detailed and data-supported reflections at the end of the assignment sequence.

While I would concur with all the points made by Silver (2016) above, it is the last two claims that scaffold the development of the RePort_Bot’s scope and goals. First, concommitant with the ability to house multimedia content such as video and audio is the fact that the presentation of many ePortfolios in HTML or XML makes these ePortfolios available to automated content extraction and indexing and computational analysis. Thus, reflections as products of ePortfolios and reflections as driven by the digital material of ePortfolios can be subject to or mediated by computational entities such as crawlers, bots, or text mining programs.

Of course, the fact that ePorfolios can be plumbed by bots or computer algorithms does not necessarily mean that it would be productive to do so. I argue that the contributions a bot like the RePort_Bot could make to the crafting of ePortfolios aligns with Silver’s (2016) valuation of self-dialogue in the course of reflection and Meloni’s (2009) practical use of GoogleDocs revision history for portfolio creation. At the same time, I would pose a different interpretation of Silver’s reading of Meloni’s article. Rather than view student utilization of GoogleDocs revision history as a case of a student using a tool to promote recall and reflection, we might also characterize the GoogleDocs platform as a semi-autonomous agent that provided students feedback that aided reflection. While not a bot in the conventional sense of the term, the GoogleDocs revision history feature does work automatically to record each version of user-generated content in a way that is denatured from the original act of writing. The GoogleDocs revision history feature re-presents the arcs of student composing—arcs which only exist in retrospect after drafting and revision has occured. The RePort_Bot seeks a similar relationship with writers of ePortfolios. The RePort_Bot returns individualized and cumulative measures of rhetorical velocity of ePortfolio content to writers in a way that humans would have difficulties replicating. These measures, generated, in a sense, behind a screen of automated number-crunching, would then provide an anterior perspective on that ePortfolio content.

The advantages of such anterior perspectives have been argued for most saliently in the field of digital humanities. Jockers (2013) offers “macroanalysis” as a complement to traditional “close reading” methodologies employed in literary analysis. Jockers (2013) takes pains to explain that macroanalysis and microanalysis have a shared goal to gather data and derive insights. They key principle of macroanalysis is that it inquires into details that are generally inaccessible to human readers (Jockers 2013, 27). Ramsay (2003) extends this point in his paragonic comparison between close reading exegesis and algorithmic criticism, musing that machines can open new pathways to analysis by allowing scholars to reformulate texts and uncover new patterns of information and organization (171). Drawing on Samuels and McGann (1999), Ramsay (2011) has elsewhere referred to the process of reformulating a text for alternative interpretations as “deformance” (33). Samuels and McGann (1999) describe deformance as a critical operation that “disorders” a text, upsetting conventional readings and placing the reader in a new relationship with the text. Embodying deformative criticism is a proposal by Emily Dickinson to read her poetry backwards as a means to unfurl aspects of language that may be obscured by conventional approaches. Ramsay (2011) extends this to the work of digital humanists, arguing that the subjection of alphabetic texts to word frequency counts or semantic text encoding is similarly deforming (35). The creation of a text concordance removes grammar and syntax from analysis, providing scholars a view of a text in which the meaning or significance of a word depends less on its contextual deployment and more on the number of times it occurs in a text. The RePort_Bot hews to this notion of deformance by providing users an unfamiliar reading of a text based on word frequency counts, text normalization, and the application of the concept of rhetorical velocity.

Rhetorical Velocity

Rhetorical velocity (see Ridolfo and DeVoss 2009; Ridolfo and Rife 2011) is generally applied to those texts that have been designed for re-use, easy repurposing, and mass circulation. Consequently, rhetorical velocity has often been associated with boilerplate writing such as press releases or media images and video. One example is Amazon’s business summary. This summary conveys basic information about the who, what, and where of Amazon and appears with little deviation across multiple financial websites such as Bloomberg, Reuters, and Yahoo Finance. By boilerplating its public profile, Amazon is able to present a unified brand image to its multiple audience and facilitates the distribution of its brand identity by giving media outlets a plug-and-play textual patch for other artifacts such as news stories or blog posts.

A rhetorical concept that governs boilerplate writing seems far removed from the type of particularity of language and topic selection that ePortfolios demand. However, there are good reasons why rhetorical velocity is specifically applicable to ePortfolios. The first reason is inflected by the question of genre. Designers may be crafting a professional ePortfolio to reflect their career fields or, for undergraduates, their prospective career fields. In this case, designers must be attentive to the disciplinary codes of their chosen professions so that their ePortfolio can be recognized by practitioners of that field. In this case, ePortfolio content will likely concentrate a few key and readily discernible thematic foci. Thus, each page of the ePortfolio is likely to have replicated language to signal the focus or theme of the ePortfolio. Indeed, certain fields such as content strategy recommend this “templatey” approach (see Kissane 2011). Tracking the rhetorical velocity of ePortfolios reflective of this case can reveal if such a focus has been linguistically achieved. Theme words would appear more regularly as structuring rhetorical elements of each page, and would be considered to possess higher rhetorical velocity because they are being reused more frequently. Conversely, the antinomy of boilerplate writing can also be tracked because rhetorical velocity is a relative measure. For certain terms to be considered “fast,” other terms would need to be considered “slow.” These “slow” terms could serve as an index of an ePortfolio’s variety in a way that is much more informative than measuring word frequency. Sheer counts may provide people with a sense of content and topicality; however, the application of rhetorical velocity to this issue allows people to measure diversity of words and style against prevailing words (i.e., words that lessen the variability of the text).

Another reason that rhetorical velocity is an appropriate analytic for ePortfolios involves sustainability. While certain ePortfolio assignments may ask people to add content as if from scratch, others, maximizing the affordances of the media, may seek to re-use content or rhetorical modes across pages/content areas. Assessing the rhetorical velocity of an ePortfolio can help writers self-audit existing content from a fresh perspective and cue people to the best approaches to extending their ePortfolios.

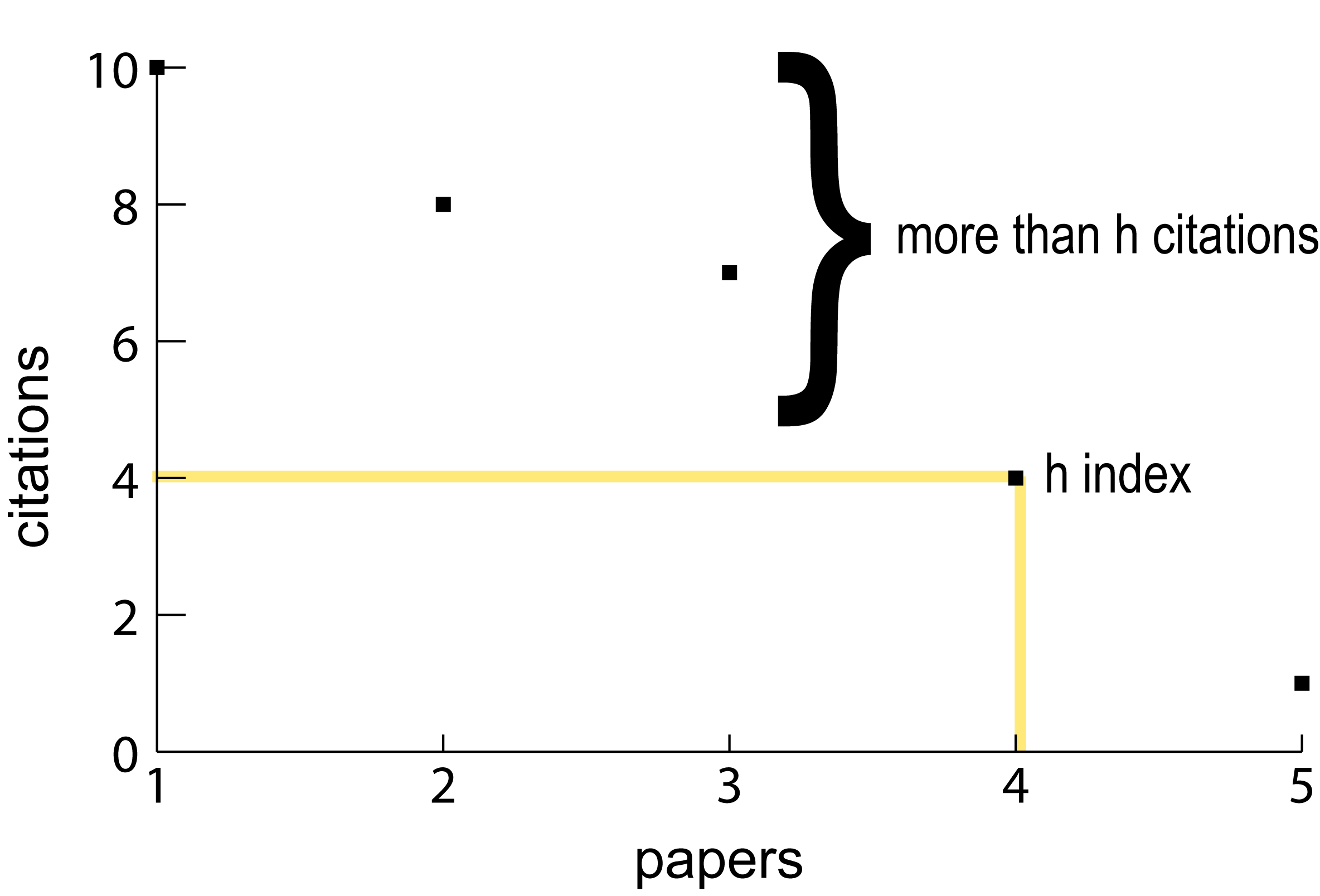

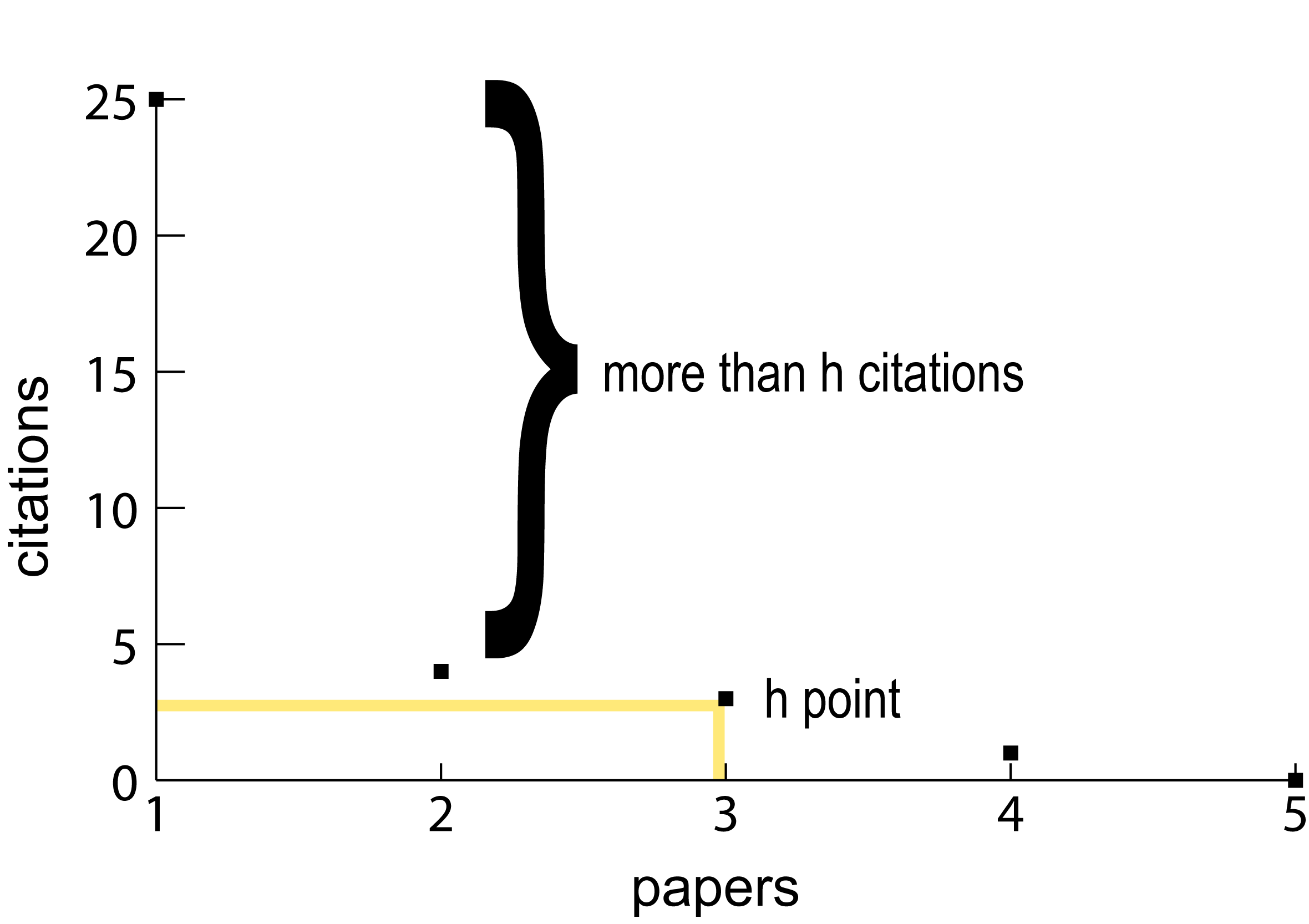

No definitive means of calculating or rendering rhetorical velocity has been established. The RePort_Bot offers a computational approach to foregrounding textual features cognate with the idea of rhetorical velocity based on the calculation of a text’s word frequency h point. Formulated by Jorge Hirsch (2005; 2007; see also Ball 2005; Bornman & Hans-Deiter 2007), the h point or h index attempts to weigh the impact of an author has in his/her discipline in a single value. This single value or h point is the point at which a publication’s rank in terms of citation count is equal to or less than the number of citations for that particular publication:

h point = (rank of citations, number of citations)

Figure 1. Author A h point Scatterplot

Figure 2. Author B h point Scatterplot

As a bibliometric, the h point functions to correct wide disparities in citation counts among authors and take a more broad accounting of citation histories. The h point describes a fixed point in a discrete distribution of quantities upon which to sort quantities, adjusting for the highest and lowest values. The RePort_Bot’s application of the h point relies on its basic formula, but departs from its bibliometric aims. Instead, the RePort_Bot uses the h point to model the rhetorical velocity of ePortfolio content. The theory behind this approach is directly attributable to Popescu and Altman (2009), who apply the h point method to the word frequencies of corpora. Words in a corpus, like citations in the original bibliometric version of the h point, are ranked by their frequency. The h point refers to that word whose rank and frequency are the same or whose frequency is nearest to that word’s rank frequency.

On the face of things, word rank-frequencies and citation rank-frequencies are quite different. The latter relies on the circulation of discrete documents; the former relies on the selection of words, which are more fungible than a published paper. However, if we consider the h point as a means to trace the syndication of objects, and focus our attention on how objects on either side of the h point are delivered. The upper-bound of the h point distribution indicates those publications that have been reused the most. The lower bounds of the h point describes publications that have been reused the least. When applied to word frequencies, the upper- bound of the h point distribution indicates those words that have been used the most. The lower bounds indicates those words that have been reused the least. According to Popescu and Altman (2009, 18), modeling a text on its word rank-frequency h point can sort the vocabulary of a text into its “synsemantic” (words that require other words for their meaning) and “autosemantic” (words that can be meaningful in isolation) constituents. Synsemantic words include function words such as prepositions, auxiliaries, articles, pronouns, and conjunctions. These are the words that make up the connective tissue of a text; thus, they are used with relatively greater frequency. Autosemantic words occur less frequently, but they include most of the meaningful content words (e.g., those that announce the topic of the text or employ the specialized jargon of the writing genre). Popescu and Altman (2009) compare the operation of synsemantic and autosemantic words to the movement of high velocity and low velocity gas particles (19). Articles, prepositions, and pronouns move faster than content words, which can be deployed with less frequency and higher effect because they have more semantic weight.

Zipf (1949) makes a similar points to that of Popescu and Altman (2009). Zipf (1949) offers the “Bell Analogy” for understanding how the “work” of words is divided. Zipf (1949) asks us to imagine a row of bells, equally spaced apart along the length of a board. A demon is positioned at one end of the board. Furthermore, the demon is charged with ringing a bell every second of the time. After each bell is rung, the demon must return to the starting point and record the bell ringing on a blackboard. This results in a round trip after each bell ringing. For the bell closest to the starting point, the demon need only make a short round trip. For the bell at the farthest end of the board, the demon will make a considerably longer trip. The metaphoric mapping of gas clouds (Popescu and Altman 2009) to bells rung by a demon (Zipf 1949) is not seamless, but the notion of movement animates both. The nearest bells in the “Bell Analogy” are easiest to ring and are equivalent to the fast-moving synsemantic works that we expect to prevail at the top of the word frequency ranks. The bells at the farthest end of the board take more effort to ring and are equivalent to the autosemantic words on the bottom reaches of the h point distribution.

Why doesn’t the demon simply opt to ring only the closest bells? Why aren’t Popescu and Altman’s (2009) gas clouds only comprised of high velocity particles? The warrant for both of these ideas is partly grounded in the truisms of language. We know that language cannot only be constituted by synsemantic function words. By definition, synsemantic words require autosemantic content words to form intelligible messages (e.g. the synsemantic term “for” requires an autosemantic object to form a meaningful expression). Our experiences with language teaches us that there will be a mix of synsemantic and autosemantic vocabularies, so the bells on the far end of the board will be rung for any given text. We can illustrate Popescu and Altman’s (2009) and Zipf’s (1949) arguments through a simple writing assignment. The task is to make a declaration about the strengths of an ePortfolio that you have created and then revise that declaration to be more concise:

Declaration: “As you can see from my CV page, I have gone to many conferences where I talked about my research.”

Revision: “As you can see from the CV page, I have presented my research at numerous conferences.”

The initial declaration and revision are making the same point. The Declaration is 20 words long; the Revision is 16 words long. The mean word length of the Declaration is 3.89. The mean word length of the Revision is 4.38. Shorter words may be easier to type taken individually (indeed, one might even say that the use of function words such as “as” and “from” require little thought and energy at all), but one needs to use more of them. Words such as “presented” may be longer and take more energy to write, but that single word accounts for two concepts in the Declaration (“have gone to” and “talked about”) with more expediency. Thus, the demon may have to walk farther down the board to ring “presented” as opposed to “gone” or “talked,” but the demon doesn’t have to make as many trips.

The hop from Zipf’s (1949) Bell Analogy, Popescu and Altman’s (2009) gaseous synsemantic and autosemantic words, to Ridolfo and DeVoss (2009) concept of rhetorical velocity is a short one. Beyond the preoccupation with metaphors of speed and movement, all three theories are concerned with (1) how a text is framed, (2) how this frame manages variability, and (3) how this management impacts the delivery of a text. The h point delineation of a text between its fast and slow moving components is another way to represent those linguistic units are that being reused and those linguistic units that are reused sparingly—if at all. While tracking degrees of reuse through a representation of an h point distribution may not give us a single numerical measurement, it can reveal the structural and rhetorical priorities of a text, which could involve the emergence of global gist or a leit motif or point to a text’s variability and vocabulary richness.

Before moving forward, I must make one defining point about my use of the categories synsemantic and autosemantic: in understanding the h point and velocity of a text rhetorically, I take the synsemantic and autosemantic labels as a general speed rating. Thus, content words such as nouns, which are generally classed as autosemantic in linguistics and word frequency studies will appear in the synsemantic category after RePort_Bot processing because those content words will be circulating “faster” than those words that appear beneath the h point. Put another way, for this article, I am more interested in the velocity of meaning-making, as evidenced by word frequency, than in tracking fixed linguistic categories.

The RePort_Bot Procedure

The RePort_Bot procedure proceeds as a combination of input/output, text normalizations, and statistical modeling steps, culminating in an HTML report. I deal with the theoretical and analytical underpinnings for each step in turn. The code for the RePort_Bot procedure and instructions on how to implement the script are provided here: https://github.com/rmomizo/RePort_Bot/tree/gh-pages.

While the code offered functions on ryan-omizo.com, I should note that modifications are needed if the script is to work with other ePortfolios due to the variegated naming conventions used for HTML and CSS selectors. The Python code that extracts textual content targets from ryan-omizo.com targets the CSS class “entry-content” of my customized WordPress theme. The current RePort_Bot script will not return useful results from pages that lack a CSS class called “entry-content” or employs the class “entry-content” for other content sections. Readers should treat the code as functional pseudo-code that invites modification. Browser Inspector tools can help users identify the proper DOM elements to use in their own scraping efforts (more instructions on editing the code can be found in the README.md file at https://github.com/rmomizo/RePort_Bot).

Input

In order to analyze ePortfolios living on the web, the RePort_Bot incorporates the Python library Scrapy (“Scrapy | A Fast and Powerful Scraping and Web Crawling Framework” 2016) for opening URLs and scraping web data. The scraper “bot” opens preselected URLs from ryan-omizo.com and captures the following elements based on their HTML and CSS identifies: links (all anchor tags with the href attribute); title (all page titles based on the presence of a <title> tag); textual content found within the div element of the class “entry-content.” The RePort_Bot outputs this information as a JSON file for further processing.

The JSON file stores the information from the ePortfolio as a series of keys with colon separated values according to the above data model:

{“content”: “Welcome to my website!”,

“links” : [“http://www.example.com”],

“title” : “Example”}Text Normalization

The quantitative analysis the RePort_Bot conduct relies on counting the words used in the ePortfolio. We must tally what is present and use these counts as a jumping off point for further analysis. In order to take meaningful counts, we must “normalize” the natural language text extracted from the ePortfolio page, which, in this case, is all of the textual data stored as “content” in the JSON file. This “norming” session smoothes subtle but less significant variations in the textual data so that we can take proper word counts. For example, in an ePortfolio of a writing and rhetoric professor, the word “student” may occur several times. Proceeding with the assumption that for a field concerned with pedagogy, we might assume that the word “students” offers significant indices with which to analyze the rhetorical content of the portfolio. The rate of occurrence for the word “students” may suggest the content priorities of this hypothetical portfolio. Further, this rate of occurrence may incline us to count all the occurrences of the word “students.” The complicating factor here is that the word “students” may occur in both upper and lower-case spellings. While “Students” or “students” may convey the same semantic meaning to readers, they will be counted a separate words by the computer because of the difference in case. For this reason, one text normalization step would be to convert all words in scraped from the ePortfolio into lowercase so that all instances of “Students” and “students” will be counted together.

The RePort_Bot applies the following text normalization processes to reduce the signal noise that the natural lexical variability of written language supplies:

- HTML tag removal – removes HTML tags that persist in the web scraping procedure using the Python package bleach (see https://github.com/mozilla/bleach)

- Lowercase – converts all string data into lower case

- String tokenization – splits natural language text strings into individual word units called “tokens.” These tokens are stored in an Python list.

- Stopword removal – deletes what are often considered function words such as articles and prepositions and pedestrian constructions involving helping verbs and verbs of existence (the stopword list used in the RePort_Bot is present in the code under the variable ‘stopwords’).

- Lemmatization – reduces words are reduced to their root dictionary representations; the most significant application of lemmatization is the conversion of plural words to their singular roots (e.g., “wolves” to “wolf” or “eggs” to “egg”).

The processing steps above are sourced from natural language processing and information retrieval. However, as Beveridge (2015) argues in his description of “data scrubbing”:

There is no universal or always-correct methodology for how data janitorial work should proceed. Data scrubbing is always a relative triangulation among a particular dataset, a project’s goals, and the analyses and visualizations that a project eventually produces.

I would further argue that each step in the text normalization protocol represents an analytical intervention into the process that will greatly influence the final form that the text assumes and are not innocent by virtue of their conventionality. For example, among text processing methods, an analyst could choose to either lemmatize words (as I have) or stem words. Stemming reduces words to their most basic alphabetic root. Depending on the stemmer, the word token “wolves” would be abbreviated to “wolv.” This reduces variability, but it does not return a real world. The RePort_Bot returns real words in attempt to strike the balance between reducing variability and retaining the integrity of the original text.

Modeling

The RePort_Bot builds models of ePortfolio pages by ranking word frequencies and dividing words into their synsemantic and autosemantic categories. Recall from the discussion of Text Normalization that the RePort_Bot eliminates what would likely constitute synsemantic function words as part of its preprocessing step. Consequently, we are not sorting between function words and content words. We are sorting only content words (i.e., semantically meaningful) into their fast and slow types. We can then use the relatively fast moving content words to achieve a greater sense of key topics and actions that are holding the text together and the relatively slow moving content word to perhaps see where the writer of the ePortfolio wishes his/her readers to linger. The RePort_Bot diagnoses the h point profiles for each page in the ePortfolio and all page content combined.

Because the RePort_Bot requires customization to be used for specific ePortfolio sites, the next section offers a tutorial for gathering, installing, editing, and executing the RePort_Bot Python script.

RePort_Bot Tutorial

Introduction

For those familiar with the Python language and installing Python libraries/dependencies, you may visit https://github.com/rmomizo/RePort_Bot/tree/gh-pages for condensed instructions.

Below, you will find an illustrative walk through of installing the RePort_Bot script to your computer, installing dependencies, customizing the RePort_Bot for your needs, and displaying the results for analysis. Note that there are multiple paths to using the RePort_Bot, but this walkthrough focuses on the most basic paths for use. For more generalized installations (e.g. installing Python to your machine), I will refer readers to existing guides. Lastly, the figures depicting command line code and the results of executing that code were created using Mac’s Terminal program.

The RePort_Bot script does not possess a generalized user interface at the time of this writing. One might call it a functional proof of concept. The modules found within the RePort_Bot script proceed in a stepwise fashion. For example, the Scrapy module will generate a JSON file. The ePortfolio script will then read this JSON file and return analytical results. The virtue of this approach is that users can customize the script to inspect any ePortfolio (or any website). Indeed, as we shall see, some XPath selectors will need to be modified to match the HTML of a given ePortfolio site.

Tools/Materials

- Command line tools (Command Line or Terminal)

- Plain Text Editor or Python Interpreter

- Web browser

Procedure

1. The RePort_Bot script is written in Python. Recent Mac computers already have a working version of Python pre-installed. Windows users can download an executable installer here:

https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-279/

2. The RePort_Bot script requires the following Python dependencies to run:

pip

virtualenv

Scrapy==1.1.0rc3

beautifulsoup4==4.3.2

bleach

lxml==3.4.1

nltk==2.0.4

numpy==1.8.0

pyOpenSSL==0.15.1

python-dateutil==2.2

pyzmq==14.3.1

requests==2.7.0

requests-oauthlib==0.5.03. Installing the above dependencies requires a command line tool or Python interpreter. For this tutorial, we will be working with command line tools because nearly all computers arrive pre-packaged with command line software. For Windows, it is called Command Line or Power Shell. For Mac, the command line tools is called Terminal.

4. To install the dependencies listed above, open your command line tool (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Command line window (Terminal for Mac)

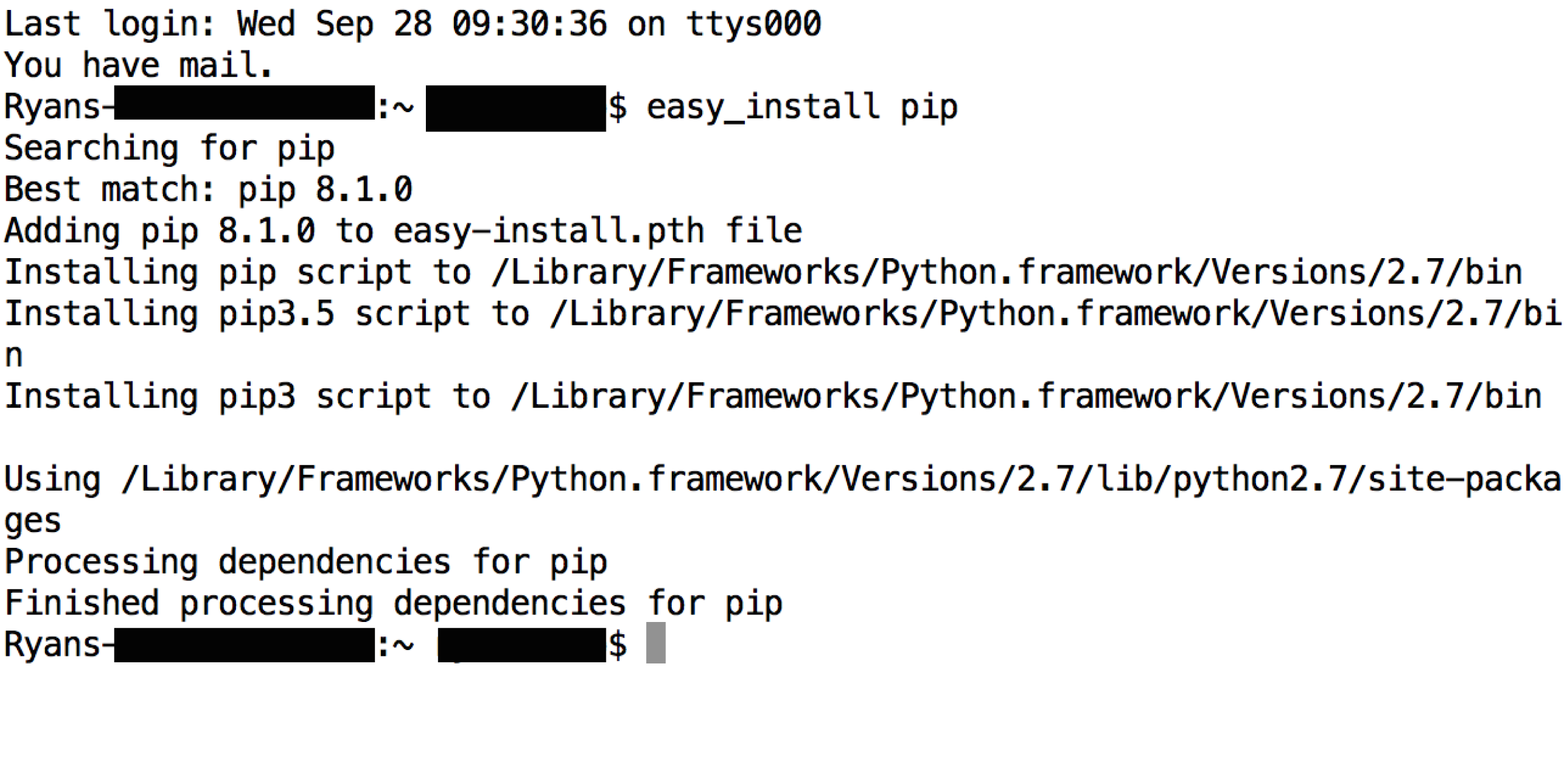

5. First we install pip. The pip library is an automatic package manager that will collect and install resources to your computer. We will use the default package manager easy_install to download. In your command line, enter the following code:

$ easy_install pip

6. A successful installation will resemble the following (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Successful pip installation

7. Next, we need to install the virtualenv dependency using pip. This virtualenv will allow us to install further dependencies in an insulated director. Ultimately, we will run the RePort_Bot script from this “virtual envelope” on your machine. To install the virtualenv package, type then execute the following in your command line tool:

$ pip install virtualenv

8. The successful installation of the virtualenv will resemble the following (see Figure 5):

Figure 5. Successful virtualenv installation

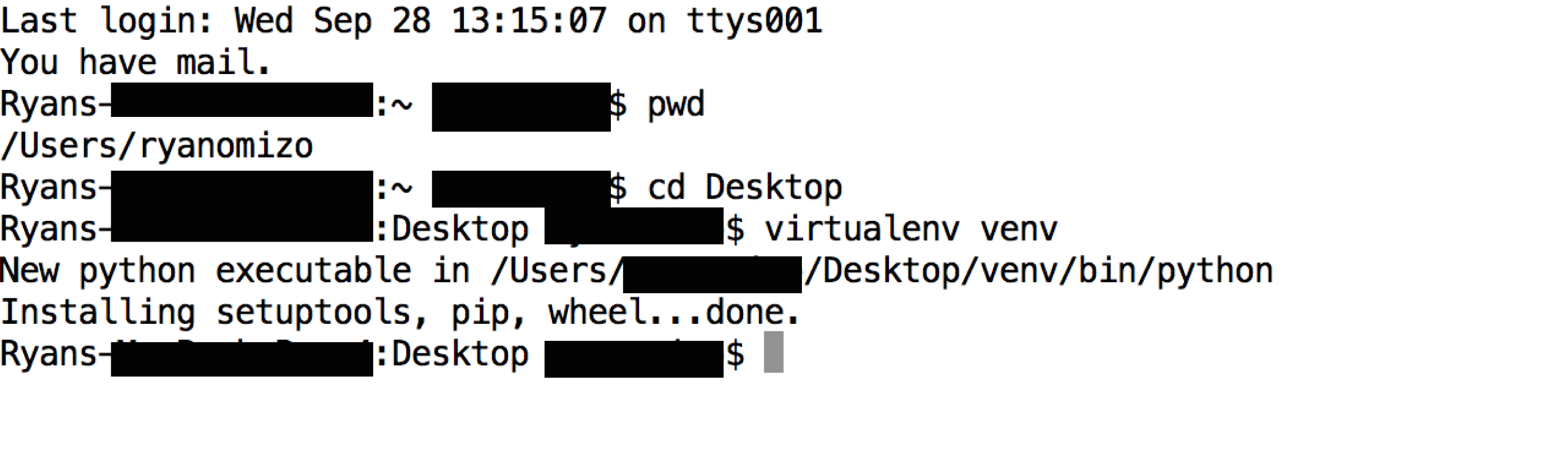

9. We can now create a virtual envelope to insulate our work with the RePort_Bot script. We are creating a directory that has its own version of Python installed. The Python installed within your computer’s framework will not be touched. Using your command line tool, navigate to your Desktop. You can place this virtual envelope anywhere you wish, but for expediency, I am placing the virtual envelope for this tutorial on my Desktop.

The command will follow this basic sequence:

$ virtualenv [name_of_envelope]

I will be calling the virtual envelope for this tutorial venv. The code is:

$ virtualenv venv

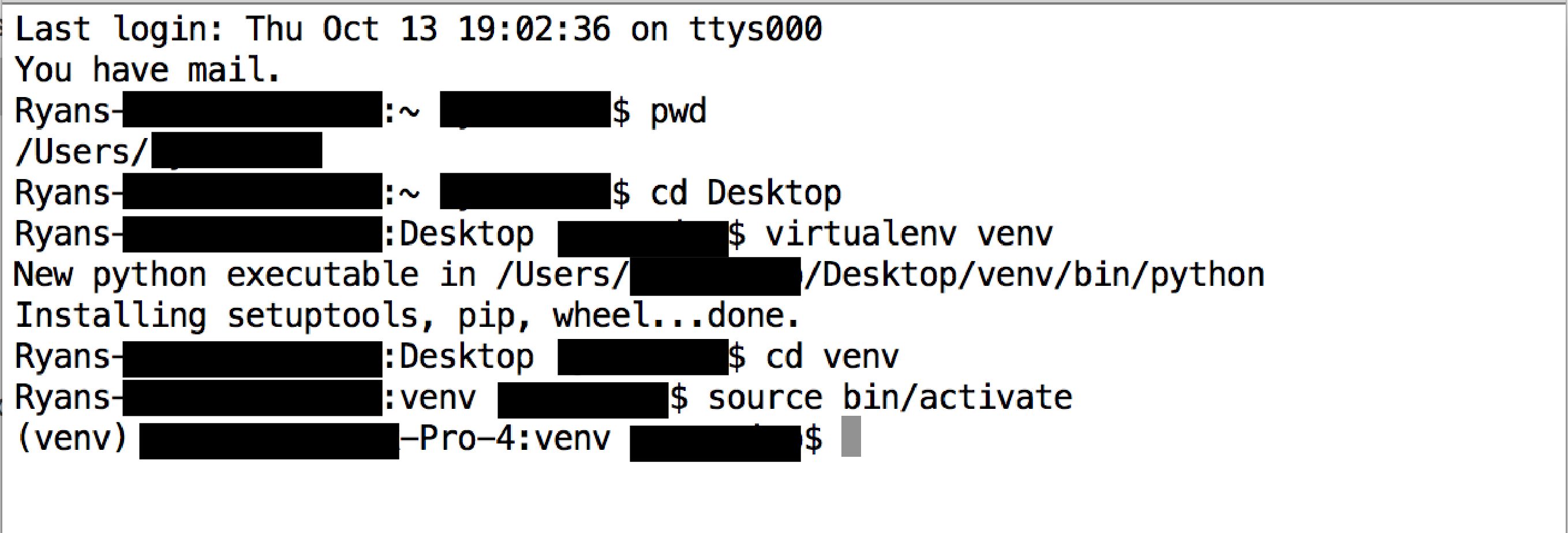

10. Navigate inside venv via the command line.$cd venv

11. Activate the venv virtual environment by entering:

$ source bin/activate

You will see a change to the command line interface. The name of our virtual environment now leads the shell prompt (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Active Python virtual envelope

*!Note: To deactivate your virtual environment, enter deactivate.

12. With the venv active, we can install the remaining dependencies using pip. For this tutorial, we will manually install each of the dependency packages listed above using the following syntax:

$ pip install [package_name]

For a concrete example:

$ pip install Scrapy==1.1.0rc3

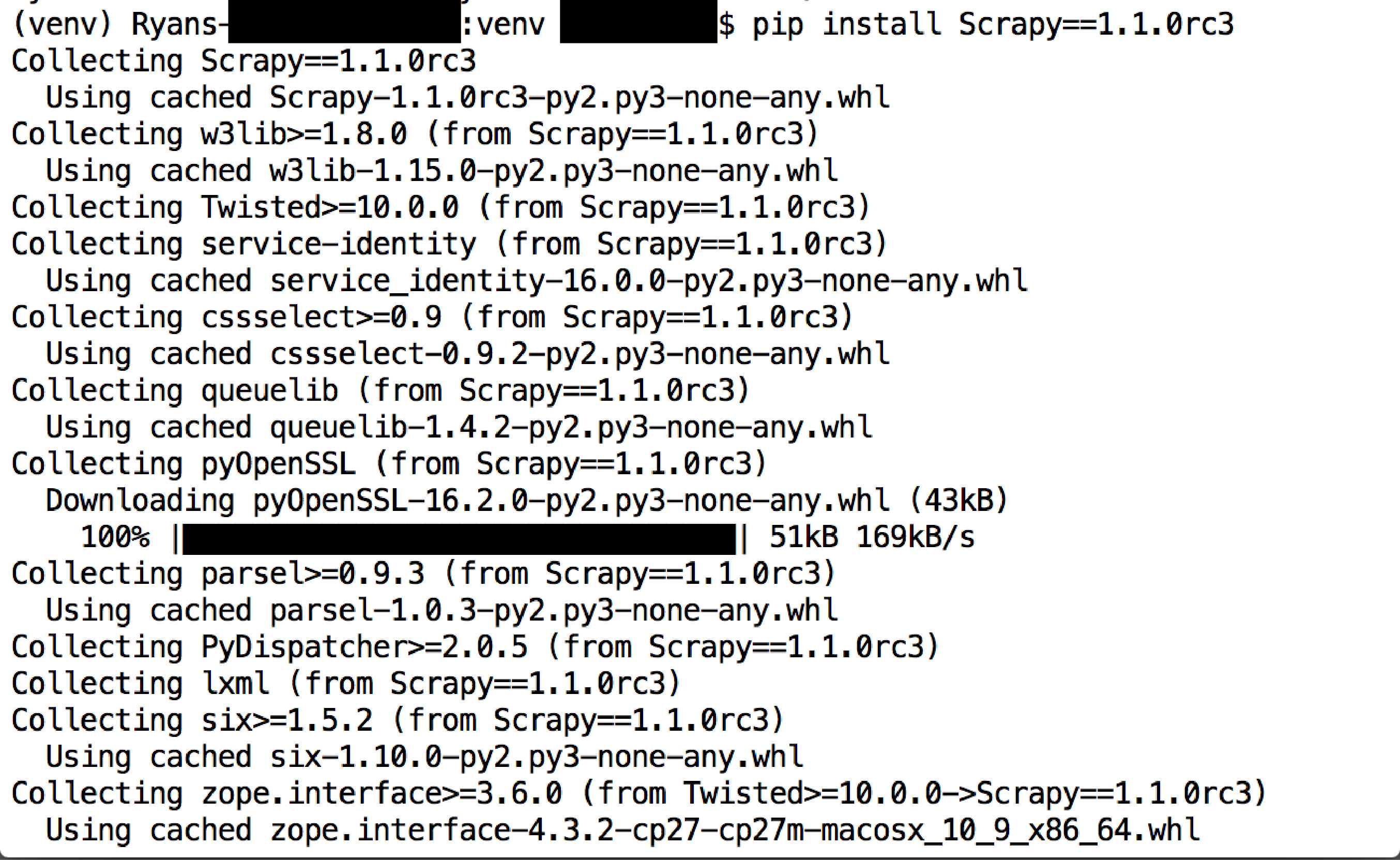

Do this for each package listed above to insure the proper installation. You will see a range of feedback in your command line interface. This code indicates that pip is working to download and install the required Python libraries to the virtual environment (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. pip installation of Scrapy to virtual environment

*!Note: there are means to install a list of Python libraries using pip and an external .txt file. Handy instructions for this process can be found on this stackoverflow thread: http://stackoverflow.com/questions/7225900/how-to-pip-install-packages-according-to-requirements-txt-from-a-local-directory.

13. With the packages listed above installed, the virtual envelope venv is ready to run the RePort_Bot script. Download or clone the entire RePort_Bot-gh-pages repository from Github here:

https://github.com/rmomizo/RePort_Bot/tree/gh-pages

14. Once downloaded, unzip the RePort_Bot-gh-pages repository in the venv directory we have created for this walkthrough.The RePort_Bot-gh-pages repository contains several required directories that are necessary for the operation of the RePort_Bot script. These directories and files placed therein can be edited to alter the scope of the RePort_Bot analytic and the appearance of the results. For this walkthrough, I will only focus on editing and executing those files that will return the type of results featured in this article.

15. Locate the settings.py file in venv > RePort_Bot-gh-pages > RV > portfolio > portfolio.

16. Open this file in your plain text editor of choice or Python Interpreter. You should see the following Python code:

# Scrapy settings for portfolio project

#

# For simplicity, this file contains only the most important settings by

# default. All the other settings are documented here:

#

# http://doc.scrapy.org/en/latest/topics/settings.html

BOT_NAME = 'portfolio'

SPIDER_MODULES = ['portfolio.spiders']

NEWSPIDER_MODULE = 'portfolio.spiders'

# Crawl responsibly by identifying yourself (and your website) on the user-agent

USER_AGENT = 'portfolio (+http://www.ryan-omizo.com)'

17. For this step, you will replace the USER_AGENT variable with the name of your website (if you have one). This will identify your bot to those ePortfolio sites that you wish to scrape and analyze. Replace the current URL (in red) with your own website, leaving the + in place. If you do not have a personal website, you may skip this step.

USER_AGENT = 'portfolio (+http://www.ryan-omizo.com)'18. Save settings.py.

19. Locate the crawler.py file in venv > RePort_Bot-gh-pages > RV > portfolio > portfolio > spiders and Open crawler.py in your plain text editor. You should see the following Python code:

import scrapy

from scrapy.spiders import CrawlSpider, Rule

from scrapy.linkextractors import LinkExtractor

from portfolio.items import PortfolioItem

from scrapy.selector import HtmlXPathSelector

from scrapy.contrib.spiders import CrawlSpider, Rule

import bleach

class PortfolioSpider(scrapy.Spider):

name = "portfolio"

allowed_domains = ["ryan-omizo.com"]

def start_requests(self):

yield scrapy.Request('http://ryan-omizo.com/', self.parse)

yield scrapy.Request('http://ryan-omizo.com/cv-page/', self.parse)

yield scrapy.Request('http://ryan-omizo.com/research-page/', self.parse)

yield scrapy.Request('http://ryan-omizo.com/teaching-page/', self.parse)

yield scrapy.Request('http://ryan-omizo.com/experiments-blog-page/', self.parse)

def parse(self, response):

item = PortfolioItem()

item['start_url'] = response.request.url

item['title'] = response.xpath('//title/text()').extract()

item['content'] = response.xpath('//div[@class="entry-content"]').extract()

item['links'] = response.xpath('//a/@href').extract()

yield item

20. The above Python code imports the required dependencies to run crawler.py. Notice the URL information in the def start_request(self) function:

yield scrapy.Request('http://ryan-omizo.com/', self.parse)

yield scrapy.Request('http://ryan-omizo.com/cv-page/', self.parse)

yield scrapy.Request('http://ryan-omizo.com/research-page/', self.parse)

yield scrapy.Request('http://ryan-omizo.com/teaching-page/', self.parse)

yield scrapy.Request('http://ryan-omizo.com/experiments-blog-page/', self.parse)

These URLs point to different pages in my ePortfolio hosted at http://ryan-omizo.com. To apply the RePort_Bot script to a different ePortfolio, replace the URLs in crawler.py with those matching the targeted ePortfolio.

21. Save crawler.py with your plain text editor or Python interpreter.

22. The next edit to make in crawler.py is to the def parse(self, response) function. This function parses the HTML elements in your page. For ryan-omizo.com, the div class entry-content contains the primary page content for all pages. For best results, you should target theat div that contains most of the text in the ePortfolio. You can track this by using inspector tools found in browsers such as Firefox or Chrome or you can view the page source in the browser.

def parse(self, response):

item = PortfolioItem()

item['start_url'] = response.request.url

item['title'] = response.xpath('//title/text()').extract()

item['content'] = response.xpath('//div[@class="entry-content"]').extract()

item['links'] = response.xpath('//a/@href').extract()

yield itemTo target the div id or class specific to an ePortfolio, replace the XPath selector (in red) associated with the item['content'] variable:

item['content'] = response.xpath('//div[@class="entry-content"]').extract()*!Note: HTML selectors can vary greatly. It may be necessary to target an id rather than a class or a default HTML element such as <body>. For a reference to using selectors with Scrapy, see https://doc.scrapy.org/en/latest/topics/selectors.html.

23. Save crawler.py.

24. With the RePort_Bot script customized, we can now execute the RePort_Bot script through our virtual envelope. Using command line tools, enter into the spiders directory. Because you should currently be in the venv virtual envelope, you can use the following code:

$ cd RV/portfolio/portfolio/spiders

25. Run the scrapy spider by entering the following code through the command line interface:

$ scrapy crawl portfolio -o items.json

26. The code will generate an items.json file in your spider directory. This JSON file contains all HTML content scraped by Scrapy. You can consider this the “raw” data for the RePort_Bot analytic.

27. Activate the Python interpreter in your command line interface by entering the following code:

$ python

*!Note: if you are using a Python interpreter such as PyCharm or Anaconda, then you may skip to step 28.

28. With Python active, we can import the Python file that will apply the RePort_Bot analytic to the scraped content found in items.json by entering the following commands:

>>>import ePortfolio>>>from ePortfolio import *>>>make_report('items.json')

29. The above code will analyze the items.json content and generate an HTML file called report.html, which contains the results of analysis. You can open this file in your browser with CSS styles and JQuery interactivity already applied.

*!Note: The CSS and JQuery script for report.html can be found in venv > RePort_Bot-gh-pages > portfolio > portfolio > spiders as report.css and jquery.tipsy.js respectively. You can edit these files to customize the appearance and interactivity of the RePort_Bot results.

30. See sample results here:

http://rmomizo.github.io/RePort_Bot/report

For the interpretation of the above results, see the Output/Analysis section below.

Output/Analysis

In this section, I illustrate the RePort_Bot output via sample runs on my own ePortfolio site: ryan-omizo.com. This site is divided into 5 main pages: landing page, CV, Teaching, Research, and Experiments blogroll. I elaborate on the data visualizations through close, reflective analysis of these results. Summative statements about the applicability of the RePort_Bot can be found in the Use Cases/Conclusion section below. The actual report generated by the RePort_Bot on ryan-omizo.com can be accessed here: http://rmomizo.github.io/RePort_Bot/report. Readers can interact with the charts as an accompaniment to the following analysis.

I have chosen to deploy the RePort_Bot on my own professional portfolio because this type of self-reflective work is a primary entailment of composing ePortfolios and fundamental to ePortfolio pedagogy. While writing within a classroom is a social action that enrolls participants at all stages of the process, students must also refine their ability to deliberate and respond as individual actors, which also includes making decisions about their own texts after self-review or adopting the persona of an expert when reviewing others. Abrami, et al. (2009) refer to this concern as “self-regulation” (5). Yancey’s (1998) concept of “reflection-in-action” offers additional support to this position and is worth quoting at length:

Through reflection we can circle back, return to earlier notes, to earlier understandings and observations, to re-think them from time present (as opposed to time past), to think how things will look to time future. Reflection asks tahat we explain to others, as I try to do here, so that in explaining to others, we explain to ourselves. We begin to re-understand.

Reflection-in-action is thus recursive and generative. It’s not either a process/or a product, but both processes and products. (24)

Consequently, by applying the RePort_Bot script to my own ePortfolio, I am conducting the self-regulating or reflection-in-action exercises that we ask students to conduct as they work to populate and make sensible their own ePortfolios. And this self-regulation or reflection-in-action is predicated on the RePort_Bot remaking my own content so that I can approach it from an unfamiliar perspective.

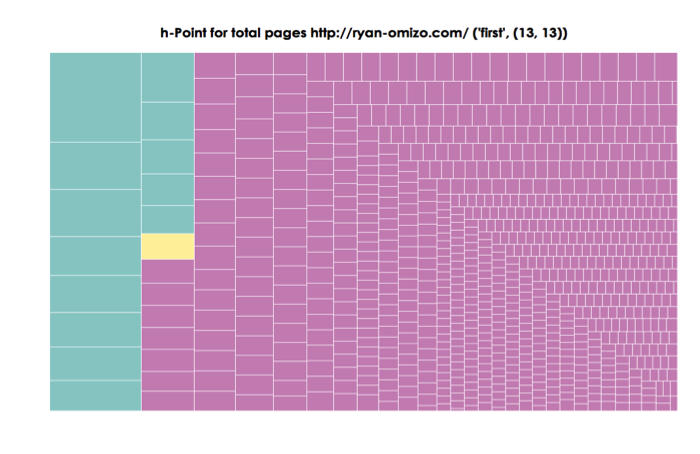

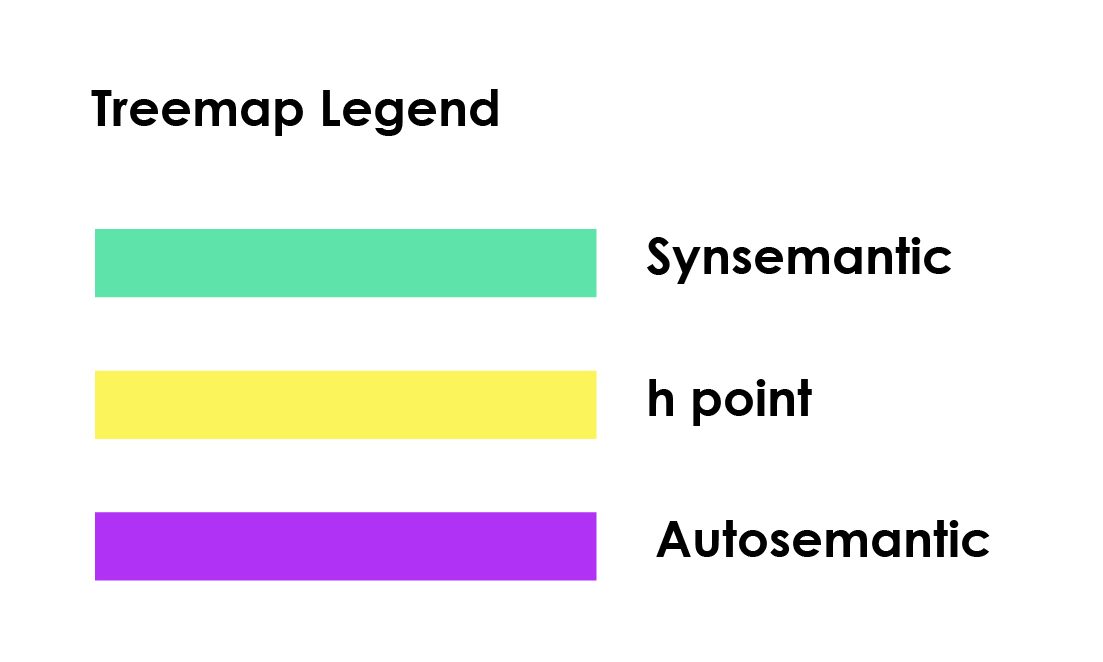

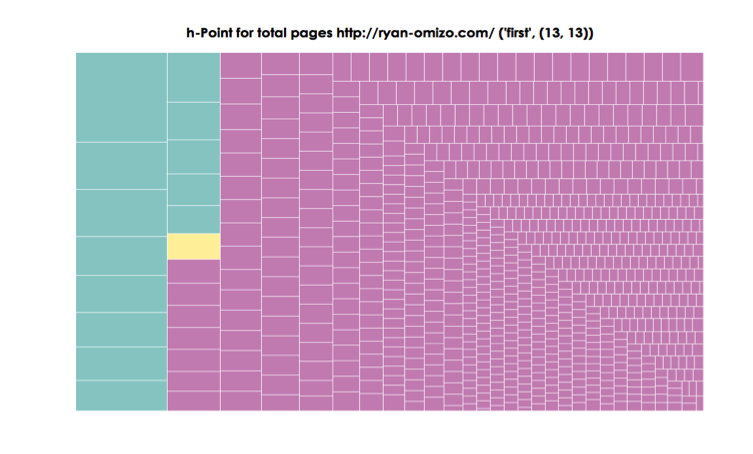

The RePort_Bot outputs an HTML page featuring treemap visualizations that graph the h point distributions of word tokens for the entire portfolio and for individual pages[1]. The synsemantic, h point, and autosemantic terms are color coded so that users can discern the breakpoint between “fast” and “slow” terms in the treemap (see Figure 8). Hovering reveals a tooltip with term and rank-frequency information. Figures 9–11 display data culled from ryan-omizo.com.

Figure 8. Treemap Color Codes

h-Point for total pages http://ryan-omizo.com/ (‘first’, (13,13))

Figure 9. Treemap of All ePortfolio Pages

Taking ryan-omizo.com as a test case for the RePort_Bot, we can start reconciling results with rhetorical aims of the website/ePortfolio. The function of ryan-omizo.com is to establish my web presence in the field of academia—specifically, rhetoric and composition, professional writing, and digital humanities. The primary means of grounding my professional academic presence is through the use descriptions of myself, descriptions of page content, and blog posts that present examples of computational work, of which, a lengthy portion is occupied by material supplementing a off-site publication (see Omizo and Hart-Davidson 2016 for further context). All of this would be considered the why and what of this professional/academe-anchored ePortfolio. The RePort_Bot findings focus on how I am implementing this strategy and crafting an ethos.

The first treemap visualization (Figure 9) accounts for the total term frequencies and ranks in the entire ePortfolio. The h point (‘first’, 13, 13) seems rather innocuous as a separator of synsemantic and autosematic terms in the ePortfolio’s vocabulary. Terms such as (“writer”, 14) and (“rhetoric”, 17) that fall in the “fast” synsemantic category parallel the avowed ethos of rhetoric and composition academic. However, also occupying the “fast” synsemantic region of the rank-frequency distribution are more idiosyncratic. Terms such as (“author”, 1, 78) and (“sentence”, 2, 41) seem to relate to the discipline of rhetoric and composition, but their high rank-frequency suggest that something more is occurring. Indeed, the reason these terms appear with such high rank-frequency is because they are part of an extended blog post that contains a supplement to a print article. Of course, determining the provenance of a term’s rank-frequency does not convey higher order rhetorical information—especially to the writer of the ePortfolio under inspection. The information in this treemap does suggest that primary content of ryan-omizo.com (defined by length and vocabulary richness) is skewed toward a single blog post in the Experiments section. The insight here implicates the arrangement of the ePortfolio as opposed to the topics considered.

ryan-omizo.com |

h-point (u’writing’, (2,2))

Figure 10. Treemap visualization of landing page

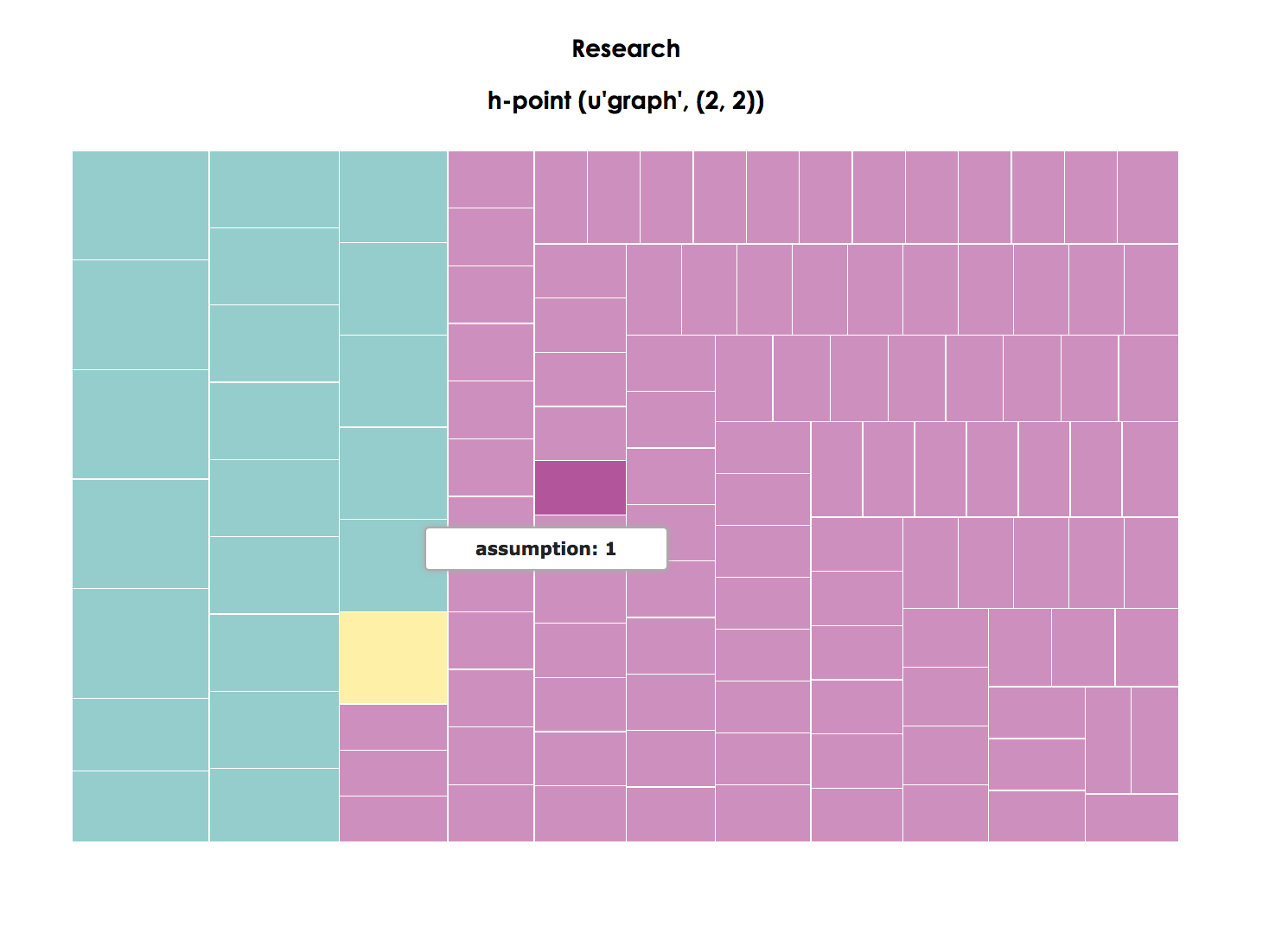

Research

h-point (u’graph’,(2,2))

Figure 11. Treemap visualization of Research page

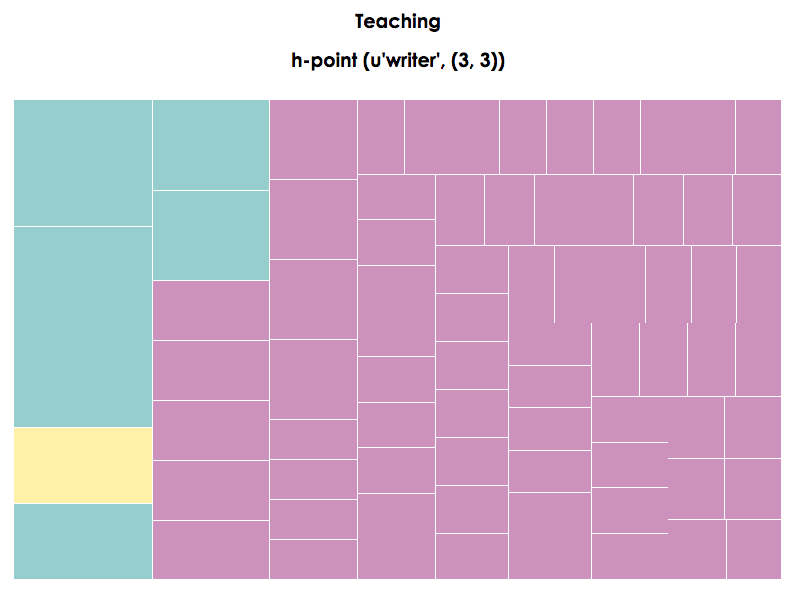

The second (Figure 10) and third treemaps (Figure 11) also seem to return the expected results. The brevity of both pages translates into scant distinctions between synsemantic and autosemantic terms. Moreover, the landing page features “fast” terms such as “rhetoric,” “composition,” “writing,” and “university”—all of which reiterate institutional affiliation and academic training. However, it is the fourth treemap that visualizes Teaching (Figure 12) that, upon personal reflection, returns surprising results. The highest ranked term in that page is “must,” suggesting that the content on that page emphasizes prescription—the “oughts” of what teachers and students should do to make learning happen or a univocal stance toward pedagogy. As a point of personal reflection, this is not the pedagogical stance that I wish to communicate in my ePortfolio, so this result is a surprise to this author.

Teaching

h-point (u’writer’,(3,3))

Figure 12. Treemap visualization of Teaching page

In all, the rhetorical velocity information, framed as the reuse of terms above and below the in-page h point of ryan-omizo.com, has suggested the following: (1) the content linguistic content of the ePortfolio is dominated by a single post in the Experiments blog, which functions an online resource for readers of the Journal of Writing Research; (2) the landing, Research, and CV pages return results that are typical of genre in that the circulation of terms on the page are disciplinary-specific and seem to enunciate my positionality within the field of rhetoric and composition; (3) the Teaching page suggests the use of a prescriptive vocabulary that runs counter to my actual teaching philosophy.

Use Cases/Conclusions

In this section, I offer four use cases for the RePort_Bot and make an extended point about how the use of the RePort_Bot can inform pedagogy and classroom practices. To make this latter point, I include a possible ePortfolio assignment that leverages the theoretical preoccupations of the RePort_Bot.

The first use case builds upon the Output/Analysis section above and poses the RePort_Bot as an instrument that fosters self-reflection/self-regulation. This use case is based on the assumption that writers do not always have a global perspective on their own writing (hence the need for peer and instructor feedback). Though blunt, the RePort_Bot provides an alternative perspective on the ePortfolio. This perspective does not offer definitive answers, but obliges ePortfolio writers to revisit their writing and attempt to integrate the results with their composing strategies. This act represents what Graves (1992) describes as a “nudge.” This nudge can encourage the writer to re-read his/her writing and learn to make individual course corrections.

The second use case for using the RePort_Bot involves making the ePortfolio a site for increased functional literacy (Selber 2004). The steps required to update the RePort_Bot files to make it viable for an individual’s ePortfolio can serve as a brief introduction to Python. More germane to an ePortfolio course, however, is the reconceptualization of the ePortfolio that is required before processing. Editing the RePort_Bot obliges the user to think of his/her ePortfolio not simply as a holistic showcase of exemplary work, curation, and reflection but as live web assets, accessible by human and non-human agents. Students would learn that their digital artifacts operate within an ecosystem of web crawlers and bots that are reading their ePortfolios and already repurposing their content. The RePort_Bot’s Python configuration can illuminate what this process involves. In this way, the RePort_Bot is similar in purpose to Ridolfo’s (2006) (C)omprehensive (O)nline (D)ocument (E)valuation heuristic. The CODE guide asks students to evaluate online sources in the context of the sources’ digital fingerprint (e.g., domain name, IP address, ISP, geographic location, and version history), much of which is neglected when undergraduates select materials for research. Revising the RePort_Bot for the needs of a class or individual user can perform the same type of unpacking, making students aware of their own digital fingerprint.

The third use case involves using the RePort_Bot as a research tool for a competitive review of like-minded ePortfolio writers. In a competitive review session, a writer can use the RePort_Bot to compare his/her site with a peer’s ePortfolio in order to determine how his/her ePortfolio aligns with others in his/her field according to the use of “fast” and “slow” terms. A student who is majoring in public relations and is designing a professional ePortfolio may look to the sites of industry experts and see how those experts are managing their rhetoric with the use of stabilizing and recurrent synsemantic terms and stickier, more idiosyncratic autosemantic terms. Put another way, this application of the RePort_Bot can be instructive in teaching practitioners how to mine ePortfolio for genre cues at the level of situation and syntax (Campbell and Jamieson 1978, 19; Jamieson and Campbell 1982, 146). Designers of ePortfolios can use the RePort_Bot to discover the linguistic elements that recur within known disciplinary examples in order to determine the types of elements that are characteristic of their fields.

The fourth use case for the RePort_Bot construes the RePort_Bot as a research tool for a broader genre analysis of ePortfolios. This genre research coheres with Miller’s (1984) definition of genre as goal-driven action that renders communication socially intelligible. Miller (1984) makes it clear that genre exceeds style and formal rules, indicating an “acting together” without necessary closure. While the RePort_Bot operates as a function of the presence or absence of terms in an ePortfolio, the heuristical nature of its output does engage in the type of open inquiry for which Miller advocates. The conventions and taxonomies read from the treemap visualizations are meant to complement human judgment. Moreover, the treemaps oblige a bottom-up interpretation—beginning with the frequency of word units that lay the foundation for higher-order rhetorical analysis. The empirical results of the RePort_Bot can lead to the establishment of more general rules and tendencies, but these rules and tendencies are generated by the constitution of textual inputs as opposed to imposing macro-classification schemes onto texts. In the arena of computation, the results generated by the RePort_Bot might be considered unsupervised—meaning that human coding of content has not been used to “teach” the algorithm how to label data. Consequently, a sub-use case could be made for using the processing and labeling (“fast” vs. “slow”) as a means to annotate data for other computational tasks like supervised machine learning or classification tasks.

These four use cases are presented as starting points for future elaborations. That said, communicating rhetorical concepts such as rhetorical velocity and bibliometric concepts such as the h point to students might still present challenges for instructors. To help students use the RePort_Bot in their cycles of composing, reflecting and revising, I am including a worksheet predicated on reconciling the rhetorical goals of student users and the RePort_Bot results. The tasks, as you will, see are meant to position students within a feedback loop between their drafts, their RePort_Bot results, and their goals and expectations for their ePortfolio projects. Students are obliged to first isolate data from the ePortfolio as a whole and from individual pages. They then frame the entire ePortfolio and each page in terms of their motivations. After scraping and analyzing their ePorfolio content with the RePort_Bot script, they are asked to recursively compare the measurements of the RePort_Bot with their own perceptions and then explain areas of coherence or disjunction.