Introduction

Now, more than ever, accurately assessing information is crucially important to discourse, both public and academic. Universities play an important role in teaching students how to understand and generate information. But at many institutions, learning how to effectively communicate findings from the research process is considered idiosyncratic for each field or the express domain of a particular department (e.g. applied mathematics or journalism). Data visualization is the use of spatial elements and graphical properties to display and analyze information, and this practice may follow disciplinary customs. However, there are many commonalities in how we visualize information and data, and the academic library, at the heart of the university, can play a significant role in teaching these skills. In the following article, we suggest a number of challenges in teaching complex technological and methodological skills like visualization and outline a rationale for, and a strategy to, implement these types of services in academic libraries. However, the same argument can be made for any academic support unit, whether college, library, or independently based.

Why Do We Need Data Visualization Support in Libraries?

In many ways the argument for developing data visualization services in libraries mirrors the discussion surrounding the inclusion and extension of digital scholarship support services throughout universities. In academic settings, libraries serve as a natural hub for services that can be used by many departments and fields. Often, data visualization (like GIS or text-mining) expertise is tucked away in a particular academic department making it difficult for students and researchers from different fields to access it.

As libraries already play a key role in advocacy for information literacy and ethics, they may also serve as unaffiliated, central places to gain basic competencies in associated information and data skills. Training patrons how to accurately analyze, assess, and create data visualizations is a natural enhancement to this role. Building competencies in these areas will aid patrons in their own understanding and use of complex visualizations. It may also help to create a robust learning community and knowledge base around this form of visual communication.

In an age of “fake news” and “post-truth politics,” visual literacy, data literacy, and data visualization have become exceedingly important. Without knowing the ways that data can be manipulated, patrons are not as capable of assessing the utility of the information being displayed or making informed decisions about the visual story being told. Presently, many academic libraries are investing resources in data services and subscriptions. Training students, faculty and researchers in ways of effectively visualizing these data sources increases their use and utility. Finally, having data visualization skills within the library also comes with an operational advantage, allowing more effective sharing of data about the library.

We are the Visualizing the Future Symposia, an Institute of Museum and Library Services National Forum Grant-funded group created to develop instructional and research materials on data visualization for library professionals and a community of practice around data visualization. The grant was designed to address the lack of community around data visualization in libraries. More information about the grant is available at the Visualizing the Future website. While we have only included the names of the three main authors; this work was a product of the work of the entire cohort, which includes: Delores Carlito, David Christensen, Ryan Clement, Sally Gore, Tess Grynoch, Jo Klein, Dorothy Ogdon, Megan Ozeran, Alisa Rod, Andrzej Rutkowski, Cass Wilkinson Saldaña, Amy Sonnichsen, and Angela Zoss.

We are currently halfway through our grant work and, in addition to providing publicly available resources for teaching visualization, are also in the process of synthesizing and collecting shared insights into developing and providing data visualization instruction. This present article represents some of the key findings of our grant work.

Current Environment

In order to identify some broad data visualization needs and values, we reviewed three environmental scans. The first was carried out by Angela Zoss, who is one of the co-investigators on the grant, at Duke University (2018) based on a survey that received 36 responses from 30 separate institutions. The second, by S.K. Van Poolen (2017), focuses on an overview of the discipline and includes results from a survey of Big Ten Academic Alliance institutions and others. And the final report by Ilka Datig for Primary Research Group Inc (2019) provides a number of in-depth case studies. While none of the studies claim to provide an exhaustive list of every person or institution providing data visualization support in libraries, in combination they provide an effective overview of the state of the field.

Institutions

The combined environmental scans represent around thirty-five institutions, primarily academic libraries in the United States. However, the Zoss survey also includes data from the Australian National University, a number of Canadian universities, and the World Bank Group. The universities represented vary greatly in size and include large research institutions, such as the University of California Los Angeles, and small liberal arts schools, such as Middlebury and Carleton College.

Some appointments were full-time, while others reported visualization as a part of other job responsibilities. In the Zoss survey, roughly 33% of respondents reported the word “visualization” in their job title.

Types of activities

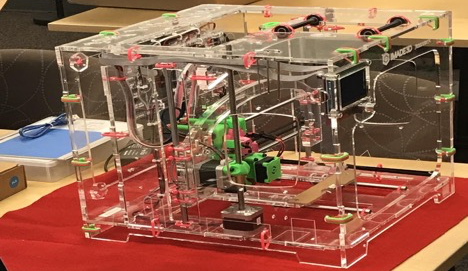

The combined scans include a variety of services and activities. According to the Zoss survey, the two most common activities (i.e. activities that the most respondents said they engaged in) were providing consultations on visualization projects and giving short workshops or lectures on data visualization. After that other services offered include: providing internal data visualization support for analyzing and communicating library data; training on visualization hardware and spaces (e.g. large scale visualization walls, 3D CAVEs); and managing such spaces and hardware.

Resources needed

These three environmental scans also collectively identify a number of resources that are critical for supporting data visualization in librarians. One of the key elements is training for new librarians, or librarians new to this type of work, on visualization itself and teaching/consulting on data visualization. They also mention that resources are required to effectively teach and support visualization software, including access to the software, learning materials, but also ample time is required for librarians to learn, create and experiment themselves so that they can be effective teachers. Finally they outline the need for communities of practice across institutions and shared resources to support visualization.

It’s About the People

In all of our work and research so far, one important element seems worth stressing and calling out on its own: It is the people who make data visualization services work. Even visualization services focused on advanced instructional spaces or immersive and large scale displays, require expertise to help patrons learn how to use the space, maintain and manage technology, schedule events to create interest, and, especially in the case of advanced spaces, create and manage content to suggest the possibilities. An example of this is the North Carolina State University Libraries’ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation-funded project “Immersive Scholar” (Vandegrift et al. 2018), which brought visiting artists to produce immersive artistic visualization projects in collaboration with staff for the large scale displays at the library.

We encourage any institution that is considering developing or expanding data visualization services to start by defining skill sets and services they wish to offer rather than the technology or infrastructure they intend to build. Some of these skills may include programming, data preparation, and designing for accessibility, which can support a broad range of services to meet user needs. Unsupported infrastructure (stale projects, broken technology, etc.) is a continuing problem in providing data visualization services, and starting any conversation around data visualization support by thinking about the people needed is crucial to creating sustainable, ethical, and useful services.

As evidenced by both the information in the environmental scans and the experiences of Visualizing the Future fellows, one of the most consistently important ways that libraries are supporting visualization is through consultations and workshops that span technologies from Excel to the latest virtual reality systems. Moreover, using these techniques and technologies effectively requires more than just technical know-how; it requires in-depth considerations of design aesthetics, sustainability, and the ethical use and re-use of data. Responsible and effective visualization design requires a variety of literacies (discussed below), critical consideration of where data comes from, and how best to represent data—all elements that are difficult to support and instruct without staff who have appropriate time and training.

Services

Data visualization services in libraries exist both internally and externally. Internally, data visualization is used for assessment (Murphy 2015), marketing librarians’ skills and demonstrating the value of libraries (Bouquin and Epstein 2015), collection analysis (Finch 2016), internal capacity building (Bouquin and Epstein 2015), and in other areas of libraries that primarily benefit the institution.

External services, in contrast, support students, faculty, researchers, non-library staff, and community members. Some examples of services include individual consultations, workshops, creating spaces for data visualization (both physical and virtual), and providing support for tools. Some libraries extend visualization services into additional areas, like the New York University Health Sciences Library’s “Data Visualization Clinic,” which provides a space for attendees to share and receive feedback on their data visualizations from their peers (Zametkin and Rubin 2018), and the North Carolina State University Libraries’ Coffee and Viz Series, “a forum in which NC State researchers share their visualization work and discuss topics of interest” that is also open to the public (North Carolina State University Libraries 2015).

In order to offer these services, libraries need staff who have some interest and/or experience with data visualization. Some models include functional roles, such as data services librarians or data visualization librarians. These functional librarian roles ensure that the focus is on data and data visualization, and that there is dedicated, funded time available to work on data visualization learning and support. It is important to note that if there is a need for research data management support, it may require a position separate from data visualization. Data services are broad and needs can vary, so some assessment on the community’s greatest needs would help focus functional librarian positions.

Functional librarian roles may lend themselves to external facing support and community building around data visualization outside of internal staff. A needs assessment can help identify user-centered services, outreach, and support that could help create a community around data visualization for students, faculty, researchers, non-library staff, and members of the public. Having a community focused on data visualization will make sure that services, spaces, and tools are utilized and meeting user needs.

There is also room to develop non-librarian, technical data visualization positions, such as data visualization specialists or tool-specific specialist positions. These positions may not always have an outreach or community building focus and may be best suited for internal library data visualization support and production. Offering data visualization support as a service to users is separate from data visualization support as a part of library operations, and the decision on how to frame the positions can largely be determined by library needs.

External data visualization services can include workshops, training sessions, consultations, and classroom instruction. These services can be focused on specific tools, such as Tableau, R, Gephi, and so on. They can be focused on particular skills, such as data cleaning and normalizing, dashboard design, and coding. They can also address general concerns, such as data visualization transparency and ethics, which may be folded into all of the services.

There are some challenges in determining which services to offer:

- Is there an interest in data visualization in the community? This question should be answered before any services are offered to ensure services are utilized. If there are any liaison or outreach librarians at your institution, they may have deeper insight into user needs and connections to the leaders of their user groups.

- Are there staff members who have dedicated time to effectively offer these services and support your users?

- Is there funding for tools you want to teach?

- Do you have a space to offer these services? This does not have to be anything more complicated than a room with a projector, but if these services begin to grow, it is important to consider the effectiveness of these services with a larger population. For example, a cap on the number of attendees for a tool-specific workshop might be needed to ensure the attendees receive enough individual support throughout the session.

If all of these areas are not addressed, there will be challenges in providing data visualization services and support. Successful data visualization services have adequate staffing, access to the required tools and data, space to offer services (not necessarily a data wall or makerspace, but simply a space with sufficient room to teach and collaborate), and community that is already interested and in need of data visualization services.

Literacies

The skills that are necessary to provide good data visualization services are largely practical. We derive the following list from our collective experience, both as data visualization practitioners and as part of the Visualizing the Future community of practice. While the following list is not meant to be exhaustive, these are the core competencies that should be developed to offer data visualization services, either from an individual or as part of a team.

A strong design sense: Without an understanding of how information is effectively conveyed, it is difficult to create or assess visualizations. Thus, data visualization experts need to be versed in the main principles of design (e.g. Gestalt, accessibility) and how to use these techniques to effectively communicate visual information.

Awareness of the ethical implications of data visualizations: Although the finer details are usually assessed on a case by case basis, a data visualization expert should be able to interpret when a visualization is misleading and have the agency to decline to create biased products. This is a critical part of enabling the practitioner to be an active partner in the creation of visualizations.

An understanding, if not expertise, in a variety of visualization types: Network visualizations, maps, glyphs, Chernoff Faces, for example. There are many specialized forms of data visualization and no individual can be an expert in all of them, but a data visualization practitioner should at least be conversant in many of them. Although universal expertise is impractical, a working knowledge of when particular techniques should be used is a very important literacy.

A similar understanding of a variety of tools: Some examples include Tableau, PowerBI, Shiny, and Gephi. There are many different tools in current use for creating static graphics and interactive dashboards. Again, universal expertise is impractical, but a competent practitioner should be aware of the tools available and capable of making recommendations outside their expertise.

Familiarity with one or more coding languages: Many complex data visualizations happen at the command line (at least partially) so there is a need for an effective practitioner to be at least familiar with the languages most commonly used (likely either R or Python). Not every data visualization expert needs to be a programmer, but familiarity with the potential for these tools is necessary.

Conclusion

The challenges inherent in building and providing data visualization instruction in academic libraries provide an opportunity to address larger pedagogical issues, especially around emerging technologies, methods, and roles in libraries and beyond. In public library settings, the needs for services may be even greater, with patrons unable to find accessible training sources when they need to analyze, assess, and work with diverse types of data and tools. While the focus of our grant work has been on data visualization, the findings reflect the general difficulties of balancing the need and desire to teach tools and invest in infrastructure with the value of teaching concepts and investing in individuals. It is imperative that work teaching and supporting emerging technologies and methods focus on supporting the people and the development of literacies rather than just teaching the use of specific tools. To do so requires the creation of spaces and networks to share information and discoveries.