Background

Grinnell College, like many small liberal arts colleges, has questioned how to remain robust and relevant in a digital age (Selingo 2013; 2017). We value knowledge for its own sake, social justice, and critical thinking; yet, we accept responsibility for equipping our students with the skills that allow them to adapt to a world of rapidly changing professional opportunities. We refused to sacrifice the former for the latter. Instead, we created a learning environment to promote both our traditional values and practical job skills. In our lab, when students research, create, and evaluate extended reality (XR) experiences, they develop the technical, social-awareness, and problem-solving skills that make them attractive candidates for twenty-first–century jobs while exhibiting liberal arts sensibilities. By developing marketable skills within the framework of core liberal arts questions and experiences, the College moves toward a future in which our educational offerings are both highly relevant and eminently sustainable.

Various characteristics of and cultures within the institution have influenced how the College has responded to the pressures of a changing academic and digital landscape. Grinnell College is a small, residential, undergraduate-only liberal arts college in rural central Iowa. The College was established in 1846 with a basis in individual intellectual pursuit for the betterment of humankind that has remained strong to today and is in evidence with the individually advised curriculum. The teaching culture is centered around small, face-to-face, discussion-based classes that explore topics according to professor interests. The College includes disciplines in the arts, social sciences, and natural sciences; but we do not have professional programs such as journalism, business, and nursing, perhaps because corporate or practical pursuits are viewed as less intellectually rigorous. The College also functions with a conservative curriculum and traditional views of faculty, who are the College employees and experts primarily responsible for helping students to grow in their own knowledge. Challenges arise when new developments conflict with traditional conditions. For example, we have seen the professionalization of College staff, with highly educated, non-faculty employees taking on more significant roles in students’ educational experiences. Additionally, we have seen changes in what students need and want from their college experience to help them succeed beyond school. Similar to other institutions and labs developing projects in XR, the College wrestles with how to remain true to our essential values while accommodating emerging needs (Szabo 2019).

The Grinnell College Immersive Experiences Lab (GCIEL) emerged from discussions at the administrative level, which identified a need to synthesize a twenty-first–century liberal arts education using emerging digital visualization technologies. GCIEL is an interdisciplinary community of inquiry and practice that allows students, faculty, and staff at the College to explore the liberal arts through XR technologies (Brown, Collins, and Duguid 1989; Wenger 1998; Wenger, McDermott, and Snyder 2002). XR is an umbrella term encapsulating immersive technologies such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR). Of these technologies, lab activity started with a focus on developing VR experiences that completely immerse the user in a simulated three-dimensional (3D) environment (Bailenson 2019; Greengard 2019; Rubin 2018; Jerald 2015); we plan on expanding into AR and MR in the future.

Participating in the hands-on process of developing VR experiences has resulted in educational benefits for students. First, students gain critical-thinking and technical skills. When working in project teams to create immersive digital content, students experience an authentic development environment using industry-standard hardware and software, which prepares them to succeed in a rapidly changing job market. From a liberal arts perspective, the development process challenges students to explore deep questions and make interdisciplinary connections. The research required for developing culturally sensitive, ethical, and historically accurate immersive digital content is both demanding and comprehensive. Compared to research methodologies privileging linear subject matter presentations, such as a term paper or a video, research for VR projects compels students to consider how elements of their chosen topic function together as an interconnected, object-oriented activity system (Engeström, Miettinen, and Punamäki 1999; Jonassen and Rohrer-Murphy 1999). To do this, students must consider multiple context-specific variables for the system they investigate, how these variables interact within historical, spatial, and social contexts, and how end users will ultimately interact with the variables in an VR environment. Second, students develop soft skills including communication and collaboration. Interdisciplinary teamwork between students, faculty, and staff is a key feature of the problem-solving experience and establishes a collaborative knowledge-generation framework. The faculty role shifts from a lecturer focused on content coverage to a coach who guides students as they navigate the “real world” challenges they encounter. Staff member roles shift from assistant to technical advisors and mentors. Student roles shift from being passive recipients of knowledge to co-creators in the learning experience. These shifts allow team members to learn from each other as they integrate their own discipline knowledge and methods into the project.

Narrative

Pedagogical approaches

Inspired by Jonassen’s concepts about teaching for solving ill-structured problems and active learning (Jonassen 2000), GCIEL’s pedagogical practices guide students through a problem-solving process in which they integrate several content domains and negotiate the unpredictable paths that emerge along the way. Jonassen, Carr, and Yueh (1998) conceptualize technology as knowledge construction “Mindtools” that students learn with, not from. Using this framework, GCIEL allows learners to function as designers using VR technologies to explore their subject matter, critically evaluate the content they are studying, and represent their knowledge in a meaningful way. This approach challenges certain traditional liberal arts attitudes about what kinds of learning are valued. While the liberal arts shies away from anything that resembles “vocational” training, GCIEL fully embraces training in practical hard and soft skills as an integrated part of content knowledge acquisition and critical thinking. We recognize skills such as software and hardware competence, digital file management, project and time management, troubleshooting, and team communication as foundations for the higher-order thinking skills that liberal arts college graduates will need throughout their lives. Thus, we intentionally teach these competencies alongside more traditional humanities topics rather than hope that learners acquire them incidentally through trial and error. In this way, GCIEL builds effective learning experiences that result in students thinking critically about VR technologies and using these technologies to examine, interrogate, and represent core liberal arts topics.

GCIEL seeks to optimize learning by maintaining a flexible, inclusive, and student-centered educational environment in which instructors “pay close attention to the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that learners bring” (National Research Council 2000, 23) to the research and development experience. By treating learners “as cocreators in the teaching and learning process, as individuals with ideas and issues that deserve attention and consideration” (McCombs and Whistler 1997, 11), GCIEL allows students to take an active role in reinventing their liberal arts experience. Heeding advice that “supplementing or replacing lectures with active learning strategies and engaging students in discovery and scientific process improves learning and knowledge retention” (Handelsman et al. 2004, 521), GCIEL emphasizes hands-on, authentic learning. Students develop products aligned with their interests and wield digital technologies in socially conscious ways within widely-ranging content domains. Students, in a focus group interview, viewed the experience as highly beneficial to their overall education. One student team member particularly valued the opportunity to learn “interdisciplinary communication on a long-term project” of a scale and duration that far exceeded what could be done within just one semester of a class (GCIEL Focus Group 2018). Another student observed that one of the most important parts of the project was how, “It feels like we’re on a team with our bosses…instead of it being very much top down” (GCIEL Focus Group 2018).

When developing VR experiences in GCIEL, Grinnell College students cultivate skills which help them adapt to rapidly-changing professional opportunities and contribute to others’ learning. Because the student-developed VR products are released as open educational resources (OER) under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, students anywhere in the world can augment their education by using and contributing to the custom-built immersive experiences. As an educational tool, VR is particularly useful for enhancing spatial knowledge representation, promoting experiential learning opportunities, increasing motivation and engagement, and contextualizing the learning experience (Dalgarno and Lee 2010; Steffen et al. 2019). The embodied experiences in VR have been found to promote empathy (Herrera et al. 2018; van Loon et al. 2018) and perspective taking (Ahn, Le, and Bailenson 2013; Yee and Bailenson 2006), both of which are particularly important within liberal education contexts that focus on preparing students to deal with complexity, diversity, and change and to promote social responsibility (“What Is Liberal Education” n.d.). The VR projects developed in GCIEL (detailed below) offer new ways to engage students in various learning experiences across widely ranging domains from history (Ijaz, Bogdanoych, and Trescak 2017; Taranilla et al. 2019; Wood, William, and Copeland 2019; Yildirim, Elban, and Yildirim 2018), second language and culture acquisition (Blyth 2018; Dolgunsoz, Yildirim, and Yildirim 2018; Legault et al. 2019), and mathematics (Sundaram et al. 2019; Nathal et al. 2018; Putman and Id-Deen 2019).

Funding instruments

Dr. David Neville, a Digital Liberal Arts Specialist at Grinnell College, spearheaded the GCIEL initiative. Dr. Neville’s background in instructional technology and design, digital game-based learning, 3D modeling, and Unity development gives him the expertise to serve as the director of the lab and act as the technical advisor on all GCIEL projects. In Fall 2016, Dr. Neville received a $10,000 planning grant from Grinnell College’s Innovation Fund (IF) to investigate the feasibility of implementing a VR lab at the College. He used the grant funds to educate faculty and staff, bring in external experts, purchase equipment, and hire students with the following financial breakdown: First, about 45% of the IF monies supported participant stipends for a summer workshop led by Dr. David Neville and Dr. Damian Kelty-Stephen. This workshop helped 10 faculty and staff members at Grinnell College learn how to use VR technologies in a curricular setting. Tweets about the workshop are archived under the #gcielsw17 hashtag. Because more people showed interest in the topic than originally anticipated, the Center for Teaching, Learning, and Assessment provided an additional $1,920 to support the extra participants who registered for the workshop. Second, about 4% of the funds paid for VR experts to present their research at the workshop. Dr. Joel Beeson, Associate Professor in West Virginia University’s Reed College of Media, presented his work on the Bridging Selma Project and the Fractured Tour app. Dr. Glenn Gunhouse, Senior Lecturer of Art History in the School of Art and Design at Georgia State University, presented a general introduction to his cultural heritage projects in virtual reality, with observations about how the technology can provide access to otherwise inaccessible objects of study (Sinclair and Gunhouse 2016). Third, roughly 15% went towards purchasing new VR hardware and software (e.g., Dell Precision 5810 with NVIDIA Quadro M5000 GPU, Oculus Rift, and Wacom tablet). Finally, about 37% of IF monies paid wages for students working on the development team for the lab’s first VR project. Supporting student development work on this project, the Institute for Global Engagement at Grinnell College contributed $6,200 to fund a one-week visit to Louisiana for site-based research.

In Fall 2018, GCIEL received $144,000 for a three-year pilot project IF grant. These monies were utilized in ways which allowed the lab to expand its influence on campus and widen its project portfolio. First, about 10% of the IF award supported a new XR speaker series, which involved bringing academics and industry representatives to Grinnell College. These experts presented on the current state of XR in their fields, shared their vision for how XR will grow in the future, and demonstrated how a liberal arts education can prepare students for a career in XR. Students gained networking opportunities with these influential thought and industry leaders. Second, about 78% of the award paid personnel costs for the development teams, including student wages (72%) for four development teams and site-based research costs (6%). Finally, GCIEL used the remaining 12% of IF monies to purchase software and hardware necessary for developing VR experiences. These included software licenses, online training, digital assets, an additional VR-capable workstation with associated hardware, and an HTC Vive. This IF support ends in Summer 2021, at which time the College will consider whether to provide permanent institutional funding for GCIEL.

Team structure and technology pipeline

After confirming faculty interest in VR at the summer workshop, we began to assemble a VR development team for a pilot project. Forming the team proved that our small liberal arts college had sufficient resources and talent on site to shoulder an ambitious digital project. This was a considerable achievement considering that larger game design studios typically have development teams with hundreds of members, each contributing deep subject-matter knowledge, software and programming expertise, visual and 3D design capabilities, technical support, and project guidance. Echoing the development team experience that students might encounter in the XR industry, we envisioned our scaled-down version of the team to include a faculty adviser, a technical staff member, and students functioning as Subject-Matter Experts (SMEs), 3D Artists, and Unity Developers. The faculty adviser would come from a field related to the project’s topic and focus on helping students learn the subject matter. The technical staff member would help students manage the project and learn essential technological skills. Each student role had unique requirements.

Typically, we recruited the project SME through the faculty member, who invited an advanced undergraduate student major from their discipline. This student may have demonstrated relevant skills while working with the faculty member on prior academic projects. Only the SME had a personal invitation to join the VR development project, unlike the 3D Artist and Unity Developer, who were recruited using an open application and interview process through the student employment portal. The SME was responsible for (a) finding, evaluating, and utilizing resources to guide project development; (b) disseminating research findings to other team members in an understandable manner; and (c) leading the team’s process and progress. We considered giving SMEs more responsibilities in directing and managing a project in order to offset the marginalization that SMEs from humanities fields may feel during the coding-heavy portions of the project when they lack technical experience compared to their teammates. This may require the SME to learn and apply instructional design theories and models, Agile software development methods (e.g., Scrum), and the Unified Modeling Language (UML) to the project.

We selected a 3D Artist based on this individual’s technical experience or interests. The Artist needed to be able to use software such as Autodesk 3ds Max, Substance Painter, and Adobe Creative Cloud software platforms (e.g., Illustrator and Photoshop), and also be willing to engage in 3D modeling and texturing, UV mapping and unwrapping, model rigging and animation, developing concept art, and storyboarding. We chose 3ds Max because it is an industry-recognized tool, and familiarity with this system should better prepare students for internships and employment opportunities. The Artist is primarily responsible for 3D asset development and animation in 3ds Max and texture creation in Substance Painter. Artists may also contribute to other aspects of the project such as writing entries for a project blog, creating turntable animations of project assets for the GCIEL YouTube channel, or presenting to students and faculty about the lessons learned during project development. The Artist’s workflow included (a) evaluating primary and secondary resources identified by the Subject-Matter Expert and any data collected through site-based research; (b) utilizing these resources and data to create 3D models and animations in 3ds Max for the VR experience; and (c) importing the FBX file of the models into Substance Painter and Unity. Within Substance Painter, the Artist uses the physically based rendering and shading (PBR) capabilities of the software platform to create albedo transparency, specular smoothness, normal, occlusion, and emission texture maps. Within Unity, the Artist creates materials with a standard specular shader and then applies the texture maps to the 3D models. The Artist may also create lighting and particle effects for the VR experience inside Unity.

We selected Unity Developers based on their technical experience or interests in the Unity integrated development environment (IDE), object-oriented design and programming principles, Unity script writing in the C# programming language, and version control and collaboration with Git and GitHub. The Unity Developers were primarily responsible for writing the code that drives the VR experience; the information provided from the SME and the team’s site-based research informs how the Unity Developer programs the functionality of the experience. The Unity Developer also needed to be familiar with or willing to learn the SteamVR Unity plugin, which allows Unity to interact with and receive input from attached VR hardware (e.g., Oculus Rift-S and HTC Vive). The workflow for the Unity Developers entailed (a) brainstorming the interactivity in the VR experience; (b) bodystorming the experience with the team to flesh out what the user experience (UX) should look and feel like and how users would potentially interact with the experience; (c) utilizing whiteboxing and method stubbing to quickly make experience prototypes; (d) running through prototype tests of the VR experience to elicit user feedback; and (e) producing a minimal viable product (MVP) that could be used to secure external grant funding or to gather data in research experiments. The MVP is a version of the VR experience with just enough features to demonstrate proof of concept and provide feedback for future product development. We uploaded major versions of the VR experiences and their MVPs to the lab GitHub repos to serve as our backups, include in students’ portfolios, and share open source resources with other educational institutions interested in developing VR experiences.

Pilot project

Dr. Sarah Purcell, the L. F. Parker Professor of History at Grinnell College, and Dr. David Neville, Director of GCIEL, launched the pilot project in late Spring 2017. They hired four students for the project development team including history student Sam Nakahira as the SME, studio art student Rachel Swoap as the 3D Artist, and computer science students Zachary Segall and Eli Most as the Unity Developers. The project began as an ambitious attempt to build a VR experience of the Uncle Sam Plantation, a nineteenth-century Louisiana sugar plantation. Unfortunately, the project had an unintentionally slow, rolling start as two team members went to study in Europe for a semester. In Summer 2017, Sam Nakahira worked with Dr. Sarah Purcell to research and write about the Uncle Sam Plantation and its inhabitants, the 19th-century sugar production methods, and the historical context that would guide the team’s development process. During Fall 2017, Zachary Segall began prototyping the VR experience, deepening proficiency in the Unity IDE, and choosing a VR interaction system for the project. Based on development problems at the time with the Virtual Reality Toolkit (VRTK), Zachary Segall chose SteamVR v. 1.2.3 as the VR interaction system. With all the team members back on campus by early 2018, the full development team visited Louisiana in January 2018 for site-based research (see Figure 1). They met immediately afterwards to begin building the VR experience. At this point, we encountered a brand new series of challenges.

Initially, the team intended to simulate the 19th-century sugarhouse and steam-powered sugar mill that had operated on the Uncle Sam Plantation. The team could access the plot plan and survey data of the plantation mansion and larger outbuildings (see Figure 2); however, we had difficulty locating documentation for the sugarhouse and sugar mill. Additionally, modeling and animating the sugar mill exceeded the skill level of our 3D Artist, who was new to the 3ds Max modeling software. We soon realized the project’s scale was far beyond what we could reasonably handle with our current resources and timeframe; so, we opted to start small and then iterate toward the larger-scale goal.

To provide a common ground for historical understanding across team members, all participated in Dr. Sarah Purcell’s two credit-hour guided-reading course on the history of American slavery that focused on Louisiana, museum curation, and public history theory. Course readings inspired the new direction for our project. To honor the humanity of the enslaved people who lived on the plantation, the team decided to refocus the project on teaching users how to interpret the home life of the enslaved. Having agreed on a new approach, the team began recreating a double-pen slave cabin, which our site-based research provided sufficient data for a digital model (see Figures 3 and 4), and designing plans for structuring the VR experience itself (see Figures 5 and 6).

We came to four critical insights as we found ourselves frequently adjusting our development pipeline. First, we needed to design the curricular content around the problems arising in the project. We initially held the course meetings separate from project-development meetings to prevent talk about the project’s technical details from overshadowing discussion about the historical topics. However, we discovered that the course topics could easily become divorced from and less relevant to the specific historical challenges that emerged naturally from the project work. We actually needed to let the project work and the historical topics inform one another in real time. Second, working together closely as an interdisciplinary team to identify problems and brainstorm solutions was essential. At first, everyone worked on their own and within their own disciplinary perspective in a disconnected divide-and-conquer approach. This left little overlap for noticing how the separate parts were not quite fitting together as a whole. Had the team been working together more closely, we could have saved time by realizing sooner that researching the sugar production was a dead end. Third, we needed alignment between the project goals and the team members’ skills, especially for technology-heavy projects. If the team members did not already have the skills when they started, the team needed to re-think the goal or to devote time and resources to help the team members acquire the necessary skills.

Fourth, and perhaps most crucially, we discovered that team members must adapt themselves to different disciplinary expectations and research styles. In particular, the approaches used in computer science and history were quite different and led to some tension. Computer science professionals reduce a design problem into small, manageable components and then rapidly iterate through prototypes to find the most effective and efficient solution. In contrast, history professionals start with library and archival research to shape the research questions, then they produce a polished document with the conclusions about the subject of inquiry. Risking oversimplification, it was as if the computer science approach tried building a complex whole from smaller, simpler parts and the history approach tried contemplating a complex whole to extract a few smaller, concrete understandings. Puzzling over how to merge these distinctly different problem-solving approaches, we began implementing a new project workflow based loosely on Scrum with two-week sprints (Ashmore and Runyam 2015; Deemer et al. 2009; Rubin 2013). This process provided a common framework for approaching the problem by breaking the whole project into smaller chunks so the SME would have a more narrow issue to explore and the Unity Developers had more tangible components to start building.

Scrum is a software development project framework that embraces iterative and incremental practices, collaborative teamwork, and self-organization. A Scrum sprint is a fixed space of time in which a product of the highest possible value is created. The sprint began with team members meeting in the GCIEL space to brainstorm and assign project tasks (see Figure 7). Members tracked their progress on these tasks using Trello, a web-based project management platform, and a whiteboard located in the team space and collaboratively addressed questions as they arose (see Figures 8 and 9). At the end of the sprint, team members met to debrief, identify new areas that needed to be developed, and reflect on what they learned with regard to both the historical subject matter and project technical skills. At appropriate stages in developing the VR experience, the development team included prototype testing in their workflow to ensure the end-users would have a favorable experience (see Figure 10). By involving all team members in this process, we improved the interdisciplinary communication and problem solving.

Second-generation projects

Having learned valuable lessons about the VR design process through the pilot project, GCIEL moved forward with three new VR projects spanning the liberal arts disciplines at Grinnell College, including recreating a Viking meadhall, creating an environment to help students visualize mathematical ideas, and creating an immersive experience to teach German language and culture.

Dr. Tim D. Arner, Associate Dean and Associate Professor of English, and Dr. David Neville lead the Envisioning Heorot Project that is building a VR experience of Heorot, the meadhall from the Old English poem Beowulf where much of the narrative happens. This immersive experience is modeled on archeological excavations of meadhalls in Denmark, England, and Iceland (see Figure 11) and on accounts from historical and poetic records from the early Middle Ages. Grinnell College students involved in the project include Ethan Huelskamp, Joseph Robertson, Maddy Smith, Anna Brew, Brenna Hanlon, Zoe Cui, Tal Rastopchin, and Michael Andrzejewski. The team plans to fill the VR meadhall with people and objects from the poem in order to help the participants exploring the space sense how the room’s layout contributes to its function as a political and social arena. The Envisioning Heorot Project will help student researchers and people reading Anglo-Saxon poetry, especially Beowulf, to understand how such civic spaces functioned in Anglo-Saxon and medieval Scandinavian culture and helped shape Anglo-Saxon social structures. While building or exploring this virtual space, students will learn to analyze how the meadhall functions in Beowulf and its analogues, to locate northern European cultures within a global network of trade and cultural influence, and to consider how movement through physical space is defined by and reinforces social roles in a particular cultural context.

Dr. Chris French, Professor of Mathematics, and Dr. David Neville lead the Math Museum Project, which allows participants to explore and interact with mathematical ideas in VR. Grinnell College students involved in this project are Nikunj Agrawal, Ziwen Chen, Alexander Hiser, Yuya Kawakami, HaoYang Li, Robert Lorch, Tal Rastopchin, Lang Song, Charun Upara, and Hongyuan Zhang. This project is inspired by the mathematical models from the late 19th century when mathematicians partnered with industrialists to model new kinds of surfaces out of plaster, cardboard, or wire. These models brought new developments in algebraic geometry and new notions of non-Euclidean geometry. Immersed within the virtual Math Museum, students can interact with visualized mathematical concepts thereby experiencing greater enjoyment and comprehension of mathematical ideas.

In one room of the virtual museum, players walk around on a large ellipsoid surface, so they experience the shape in much the same way as an insect might move around on a plaster model. The player can find the umbilic points of the shape by using a tool that measures the curvature of the ellipsoid at the current location whenever the player triggers the measuring device. Another room is inspired by models created by the German mathematician Kummer. In this space, the player can manipulate a surface by adjusting certain parameters and then can watch how the surface evolves. The player’s task is to find the values for the surfaces that Kummer built. In a third room, the player must assign colors to the vertices of a graph consisting of edges and vertices so adjacent vertices take different colors. The goal is to use the minimal number of colors. This activity teaches the notion of the chromatic number of a graph. Also, students are currently developing another room in which the player learns about graph isomorphisms by manipulating the vertices of a graph to make it look like another graph.

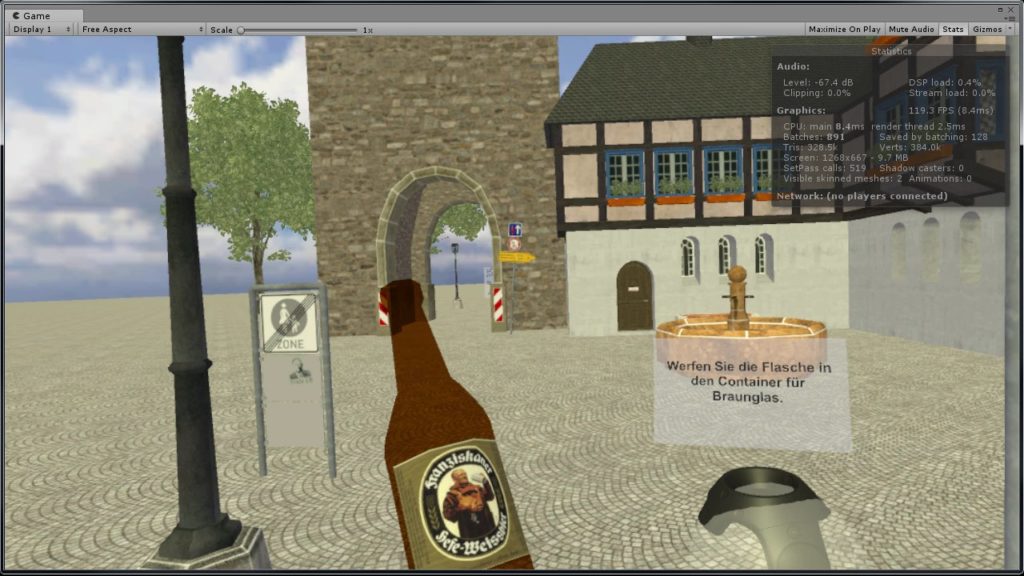

Dr. David Neville leads the German VR Project, a game for teaching environmentalism in authentic German linguistic and sociocultural contexts. Originally developed as a flat screen 3D game focusing on glass recycling and waste management systems in German public spaces, Zachary Segall and Eli Most ported the game in 2018 to create an alpha-level VR prototype (see Figure 12). Grinnell College students involved in the project include Savannah Crenshaw, Martin Pollack, Yinan Hui, Bojia Hu, Jin Hwi, Tal Rastopchin, and Michael Andrzejewski. Research on the 3D game found that goal-directed player activity provided learners of a second language and culture with a more nuanced view of the activity systems that constitute a target culture, and also apparently influenced how learners invoked and structured language in order to describe these systems (Neville 2014). The VR version of the game will expand the scope of the 3D game by including more narrative to situate the user in an authentic German cultural situation and more in-game tasks related to recycling and waste management practices. We hope that increased immersion and sense of presence in a completely virtual environment will target greater learning outcomes in second language and culture acquisition, and perhaps even realize outcomes that were not discovered in the 3D version of the game.

Next steps

We are currently refining the teams’ workflows to use Scrum methods for project management and incorporating problem-based learning theory to intentionally teach metacognitive skills (Barrows 1996; Edens 2000; Hmelo-Silver 2004; Dunlop 2005; Yew and Schmidt 2011). A victim of our own success, we face a number of challenges while scaling up the lab to support multiple VR projects simultaneously. It has been difficult to find a dedicated physical space on campus which can support a growing community of practice. As a result, GCIEL’s work remains somewhat decentralized. It also remains to be seen how much these discrete cross-curricular VR projects will transform Grinnell College’s core curricula. Likely, GCIEL’s future projects will rely on external grant support, and it may be difficult for small-scale liberal arts teams to compete with large R1 research and development labs for funding. While we are excited to see our established team members graduate and move on to high-powered tech jobs and graduate schools, this leaves recurring gaps in our project teams, so we must constantly train new students to join the project teams. Successful project teams need consistent faculty and staff time and attention; yet, College employees find themselves increasingly burdened with competing responsibilities. Overcoming these challenges depends on our ability to convince the College to change some traditional structures and to provide sufficient time and resources for experimentation. Success is not guaranteed, but we believe the effort is worthwhile.

The future of GCIEL beyond our grant funding is still in discussion. As a well-resourced institution with an individually advised curriculum, Grinnell College has a few options that we can harness to secure GCIEL’s future. For example, the Writing Lab pays student writing mentors out of their general operations budget and these students do not receive academic credit, though they do take an introductory writing course to ensure they have the necessary skills. GCIEL could adopt a similar model and teach an VR basics course to develop a pool of potential student employees as VR mentors. Another possibility is integrating the lab into existing or emerging curricular structures. VR project development would fit most seamlessly into the Mentored Advanced Project (MAP) structure as a group research project supervised by a faculty member. These MAP experiences allow students to register for 2- or 4-credit MAP research credits and work closely with faculty advisers on independent research projects. We might also be able to utilize the “Plus 2” option, which allows professors and individual students enrolled in a regularly scheduled course to plan work that would go beyond the standard syllabus. GCIEL and student VR projects may also find a place within the emerging Digital Studies Concentration or the new Film and Media Studies Program. Grinnell College’s concentrations typically involve a cross-departmental listing of various courses that meet the concentration’s themes and goals, but GCIEL could provide the seed for a concentration-specific seminar that is listed as a requirement or additional way for the students to complete credits towards the concentration. Ultimately, we want to find ways to leverage the benefits of housing GCIEL within the curriculum (e.g., rewarding students with class credits and guaranteed team members) along with the benefits of being independent from the curriculum (e.g., freedom from semester limits and ability to form multidisciplinary collaborations with skilled students, staff, and faculty). Fortunately, Grinnell College has a history of offering student learning opportunities that take many forms, including those that exist outside of traditional classroom environments.

We think all these efforts will pay off in the long run. Opening the traditional classroom format to integrate technological expertise and domain-specific content across disciplinary divides will expand student assessments beyond term papers to include scholarly products that will excite and engage a new generation of scholars in the twenty-first century. We will also have to ask: what is the best way to assess learning outcome achievement for interdisciplinary projects related to creating VR experiences? Can we identify meaningful learning outcomes we should expect of all students, such as project management and effective communication? Do we need to assess students on their domain-specific skills and knowledge, such as software troubleshooting, graphical design, or archival research? Who would be responsible for designing and evaluating these assessments? How do we more closely integrate staff and faculty roles in collaborative curriculum design, which breaks down the traditional barriers between faculty and staff roles? How do we challenge College organizational structures to harness staff expertise alongside faculty domain knowledge?

Learning from the successes of vocational and professional schools, we can reinvigorate liberal arts education with hands-on cooperative training, yet retain the focus on our traditional values that makes us unique. This new model could help to transform liberal arts institutions into laboratories for innovation in solving twenty-first–century problems. In the end we believe liberal arts graduates can—and should—have the best of both worlds: knowledge and the skills to apply it.

Key Takeaways

- Complex projects, especially ones using technology, require teams consisting of people with different technical and subject-matter competence. These projects provide excellent opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration and teaching.

- To develop transferable skills and knowledge, model the project experience on “real-world” structures. This includes treating student collaborators as equals who participate in decision-making and receive compensation (e.g., stipends or academic credit).

- Time-intensive projects will require focused, concentrated effort by team members. These projects may require institutional support for faculty involvement (e.g., reassigned time) and students to commit at least 10 hours a week to project development.

- Long-term, complex projects benefit from a permanent physical space that is equipped to support the technology, comfortably hold team meetings, and accommodate team members’ work styles, including access outside of business hours.

- The project curriculum must provide team members with the necessary prerequisite technical and subject-matter knowledge to start the project, and it must also be flexible enough in time and resources to adapt to questions that emerge during project development. As VR projects require new ways of configuring faculty-staff-student interaction and budgets to support developments, they provide excellent opportunities for institutional growth and external funding.

- When properly configured teams work on developing well-designed VR experiences, students learn valuable skills related to communication, self-directed learning, attention to detail, problem solving, negotiation, and time management.

- Development team members need to be well-versed in the ethical, psychological, and pedagogical affordances of VR and how these impact the project.

- Start small with complex projects and iterate towards larger goals.

- Open lines of communication between all team members—staff, faculty, and students—are essential to project success. Avoid isolation by encouraging teammates to pair up, even when working on components that traditionally involve many hours of individual work, such as archival research or programming. In this way, teammates can learn from the others’ processes. This supports cross-training and allows cross-pollination from diverse backgrounds/expertises. Web-based project management platforms, when used appropriately, help to facilitate this communication.

- To truly transform, institutions will have to examine deep structures: curricula, staff/faculty time, majors, and funding.