This paper offers suggestions and information for professors who seek to use 3D modeling for their own work, particularly in conjunction with undergraduate students. Overall, the paper argues that the greatest benefits of many 3D modeling projects that involve students and faculty are achieved as the pedagogical “byproducts” gleaned through the process of working through a digital humanities product rather than the actual digital artifacts or “products” of the investigation. These pedagogical “byproducts” of 3D modeling are potentially the greatest benefits particularly for those projects undertaken with modest budgets or with less technical expertise (i.e. not in institutions with highly developed digital support programs, or undertaken by professors in computer science). This is not to negate such products; this work generated several dozen 3D models of ancient objects as .stl files; a visualization of an entire section of a tomb including some of those models; an interactive visualization of a tomb with several models inside it; a video illustrating the position of objects within a different tomb; and a website to highlight some of the findings of the two summers’ work. All of those would be usable by specialists in the field of Mesoamerican art history or potentially even professors teaching a survey course on the topic. However, the skills that the participants took away from this were myriad, and very likely more important than these products themselves. Even in an imperfectly realized project in 3D modeling, digital art history (or possibly digital humanities more broadly), students learned art-historical skills, such as close looking, archival research, and in this case, particularly how recreation of context will draw upon multiple fields of investigation and methodologies, which they may choose for themselves. The project also fostered important life skills including the basics of project management, forming and fostering relationships for collaboration, and learning how to begin and drive a project when there is no clear way forward.

This idea is influenced by a seminal article by Lisa Snyder of University of California, Los Angeles’s Visualization and Modeling team “Virtual Reality [VR] for Humanities Scholarship.” She discusses the important issue, one that the team kept returning to over and over again, of understanding whether one is working on a more process-based or product-based mode. “Process-based questions are addressed through the analytical act of creating the virtual artifact or environment with little or no expectations for the longevity of the data beyond the life of the project. Product-based questions may include process-based elements during the construction of the VR environment, but are more focused on interaction with the finished product and long-term public dissemination of the research” (Snyder 2012, 396). Hoobler began the project and outlined it to her collaborators with confidence that it would yield an important product, and did not fully understand the value of working through the process of making the 3D models when, in fact, process and the opportunities for thinking through ancient spaces ultimately was equally or more important than the models themselves. It is true that all projects are to some degree a balance between these two modes, as much as there is greater emphasis on process rather than product when students (and professors) are new to the software necessary to carry out such projects. Obviously, neither of these collaborations yielded enormous products on the scale of Snyder’s own interactive VR reconstruction of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair (http://www.ust.ucla.edu/ustweb/Projects/columbian_expo.htm) or other well-funded large universities’ projects. However, work from the two summers’ projects did ultimately yield permanent products that will be helpful in future research.

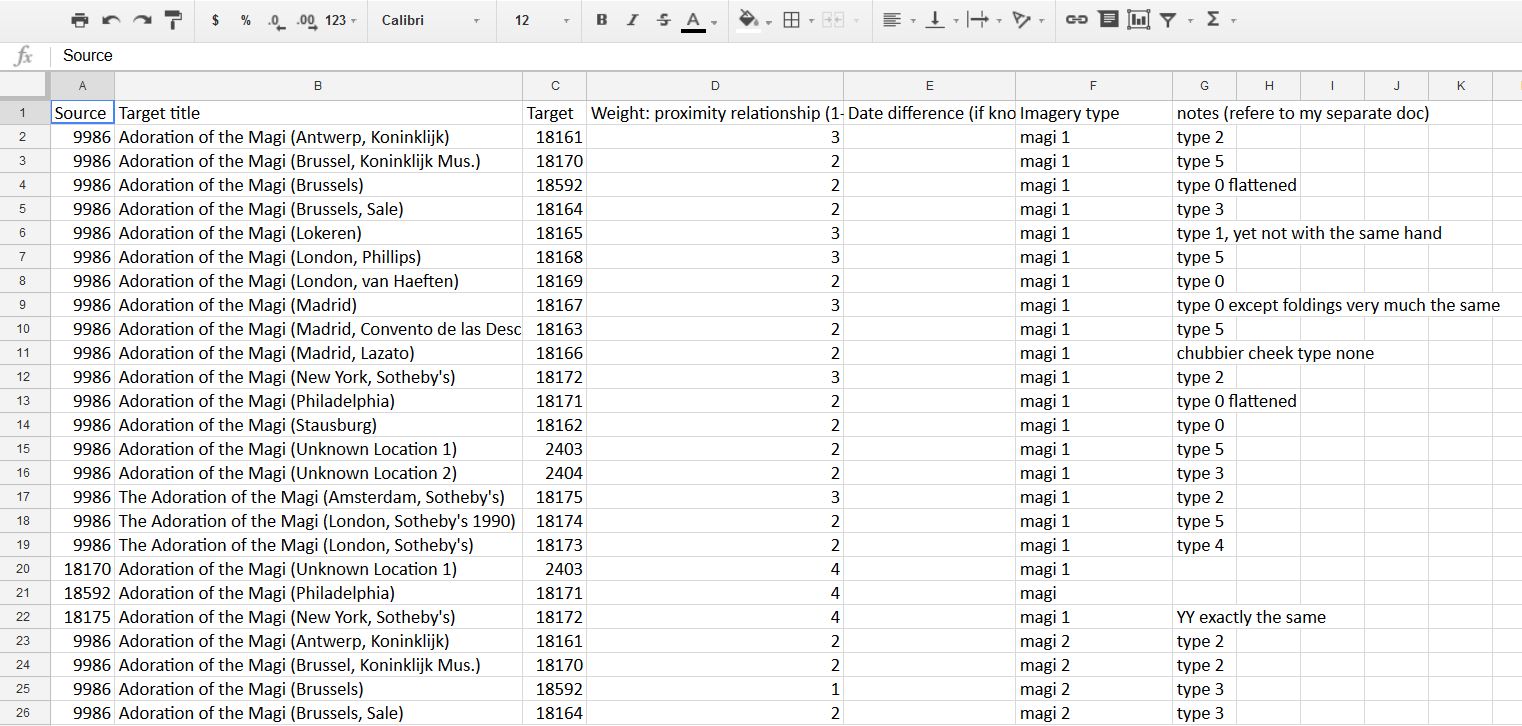

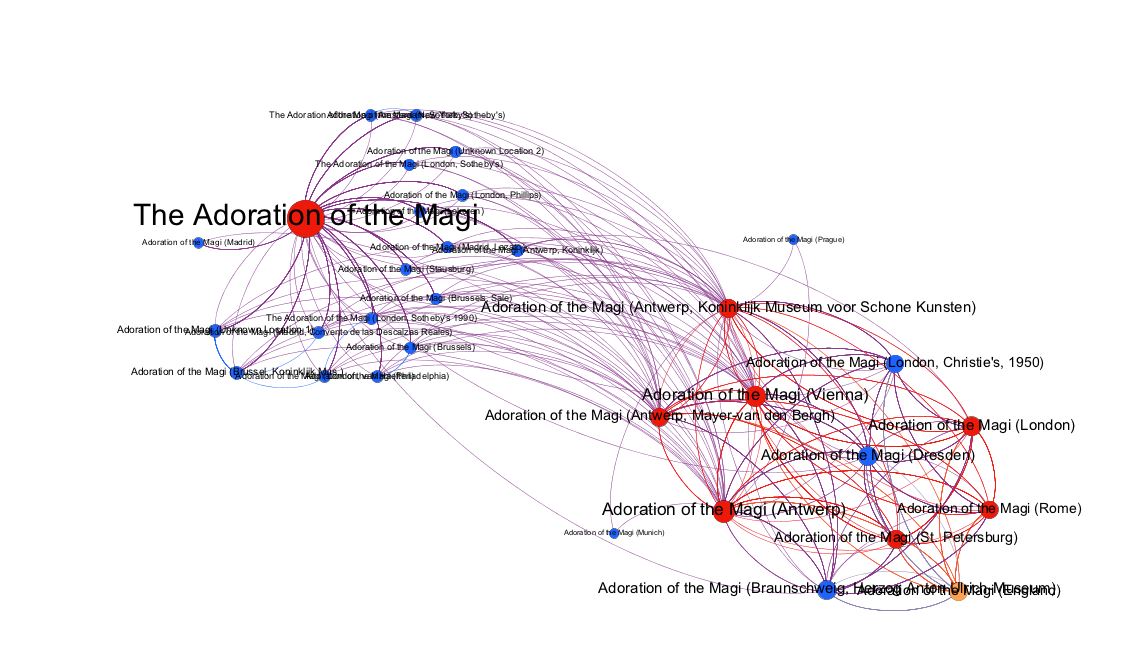

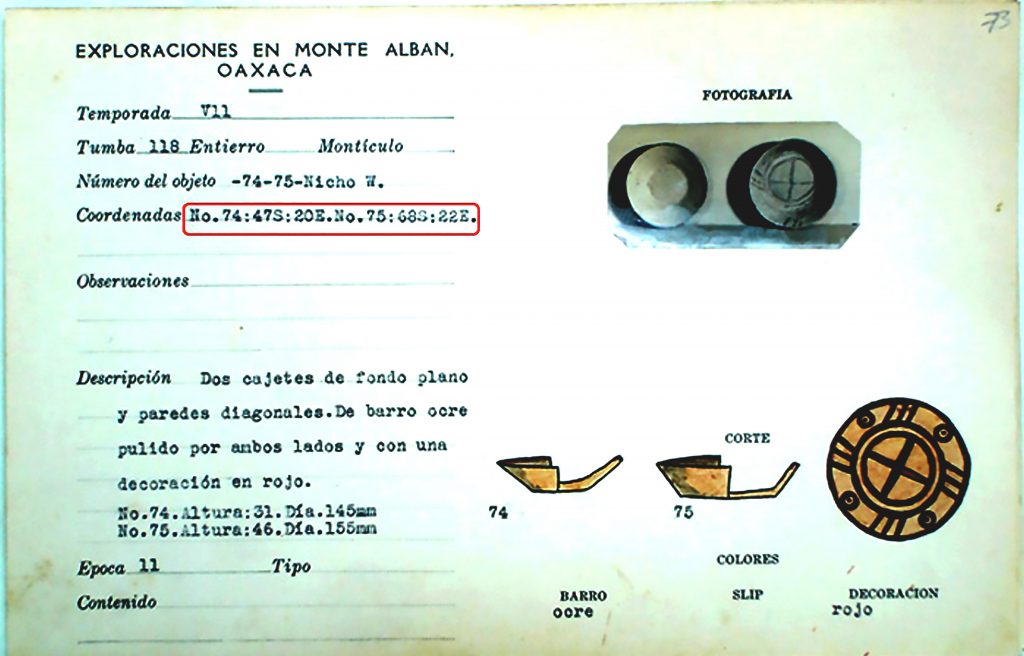

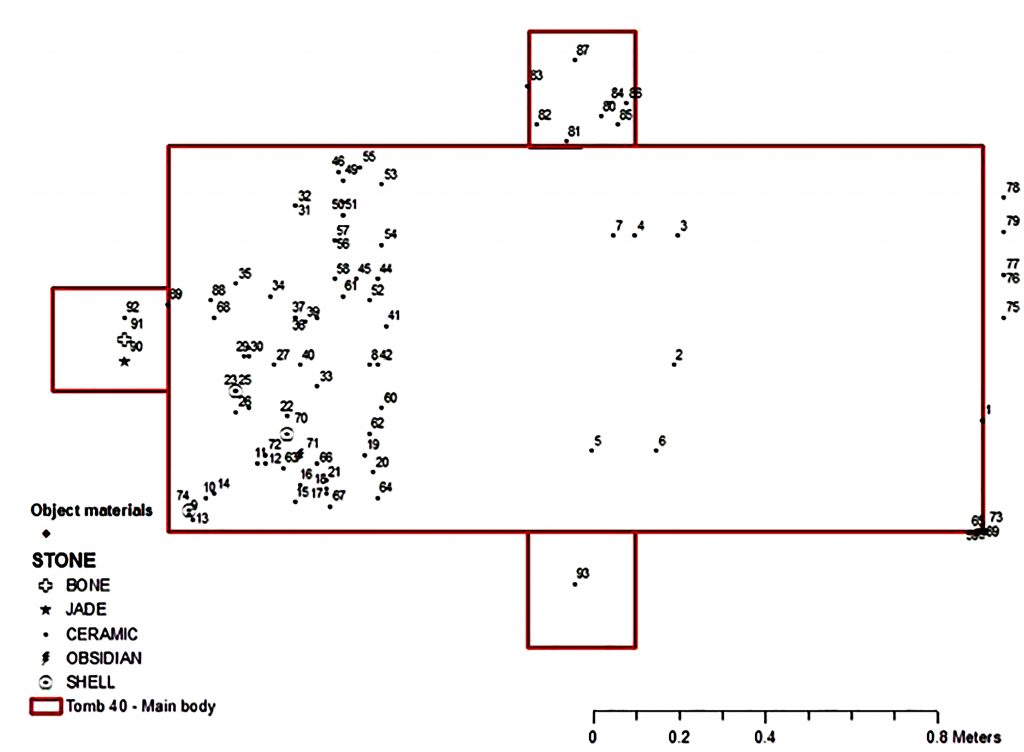

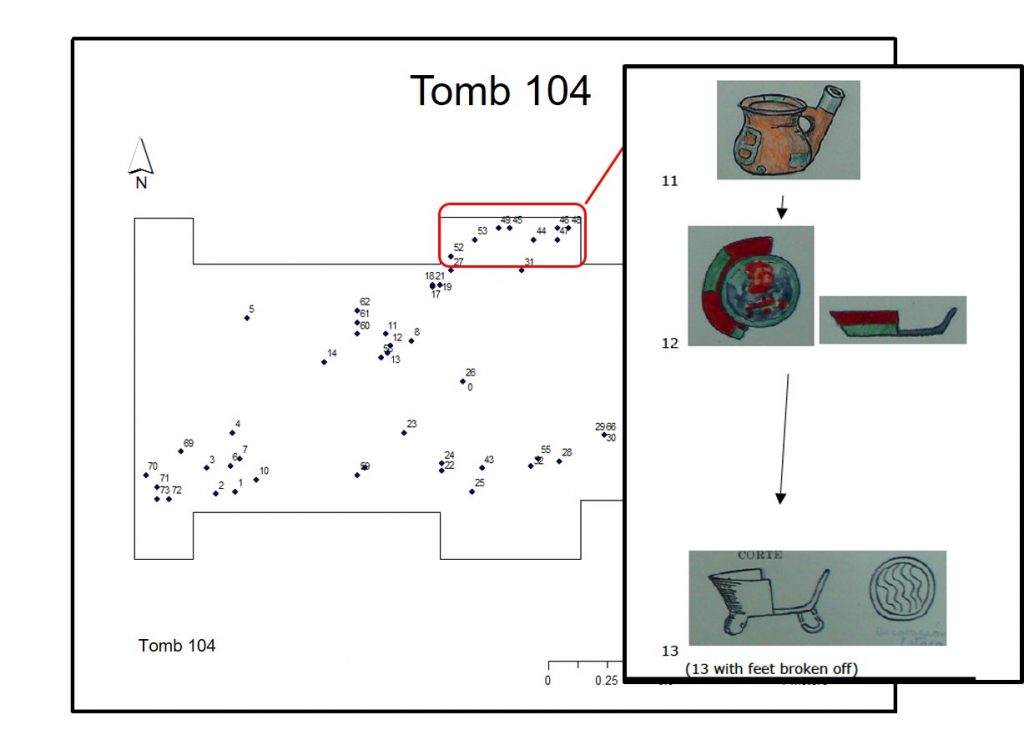

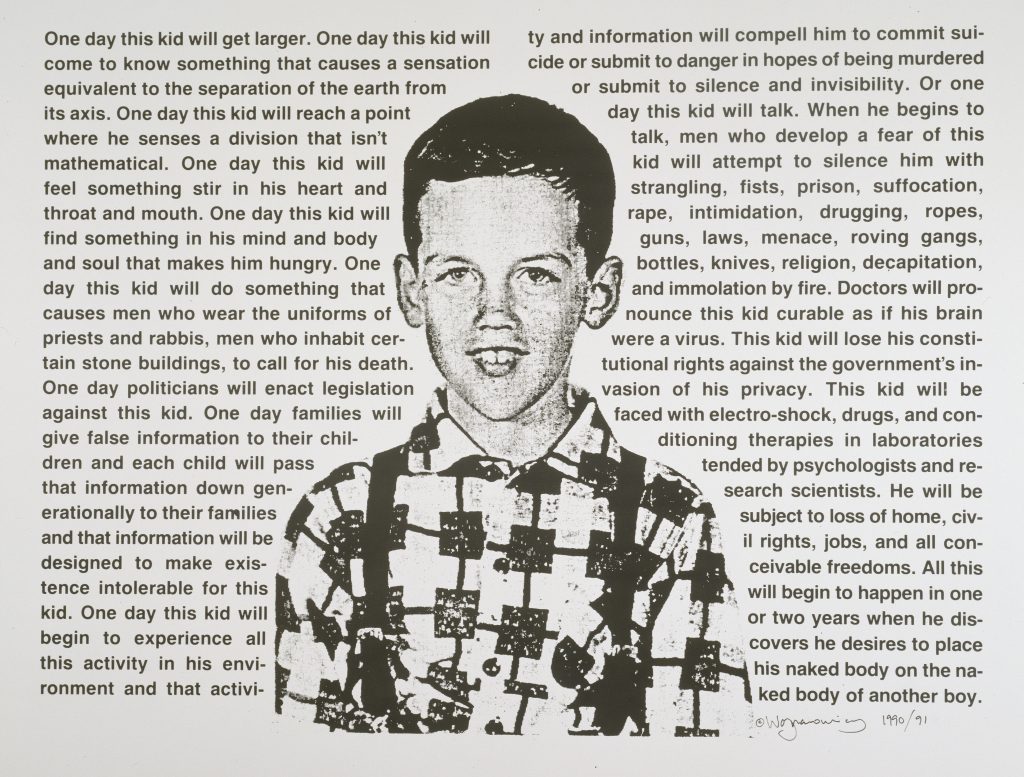

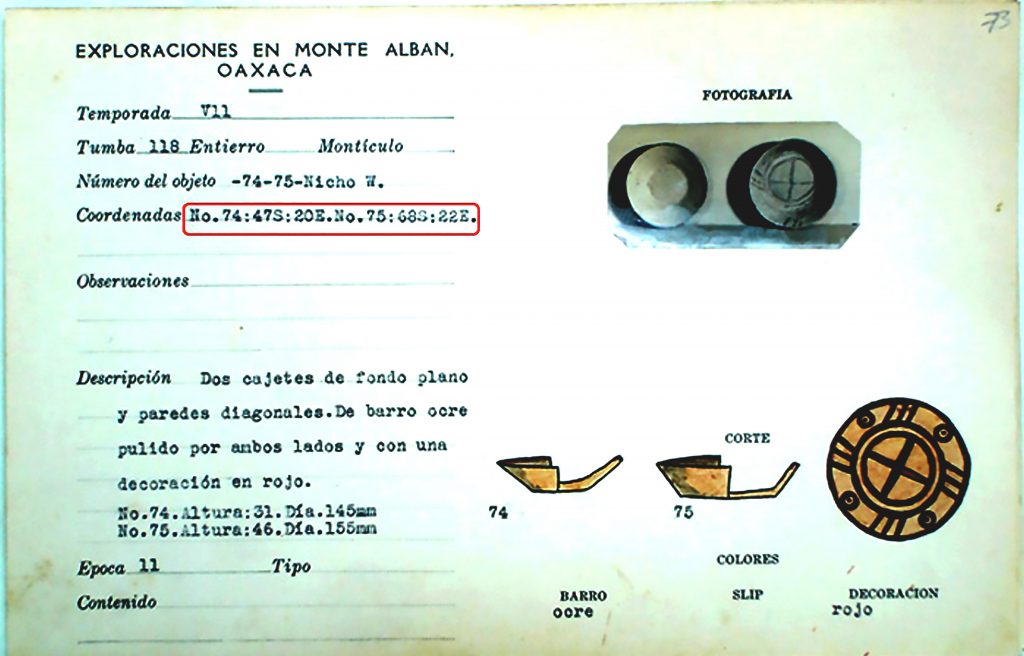

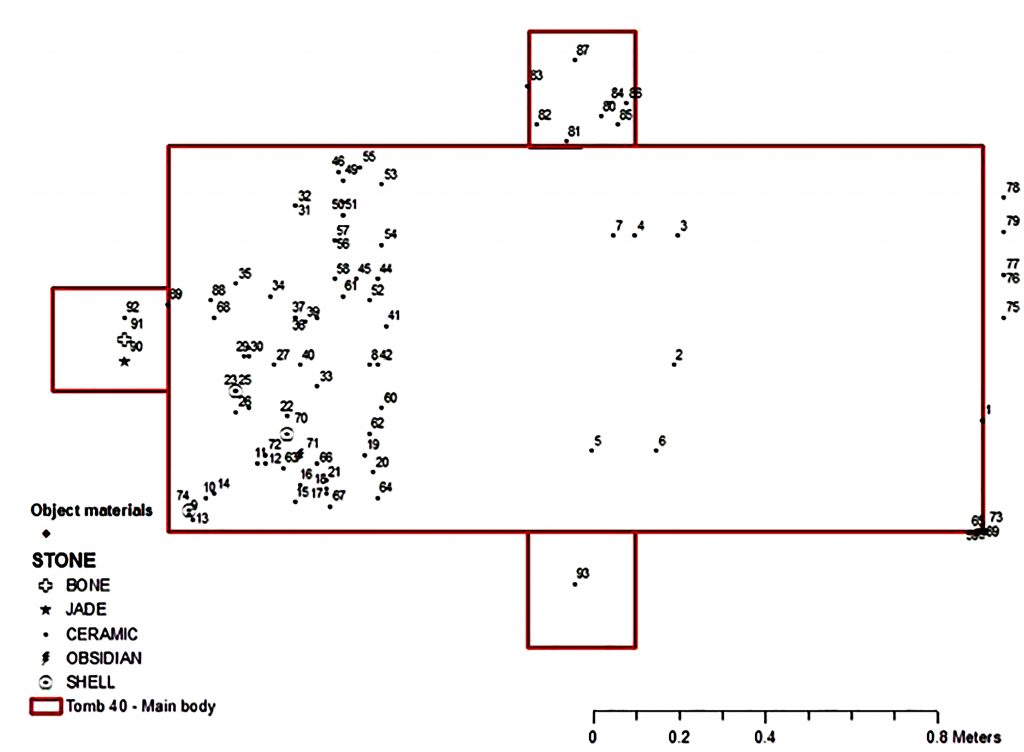

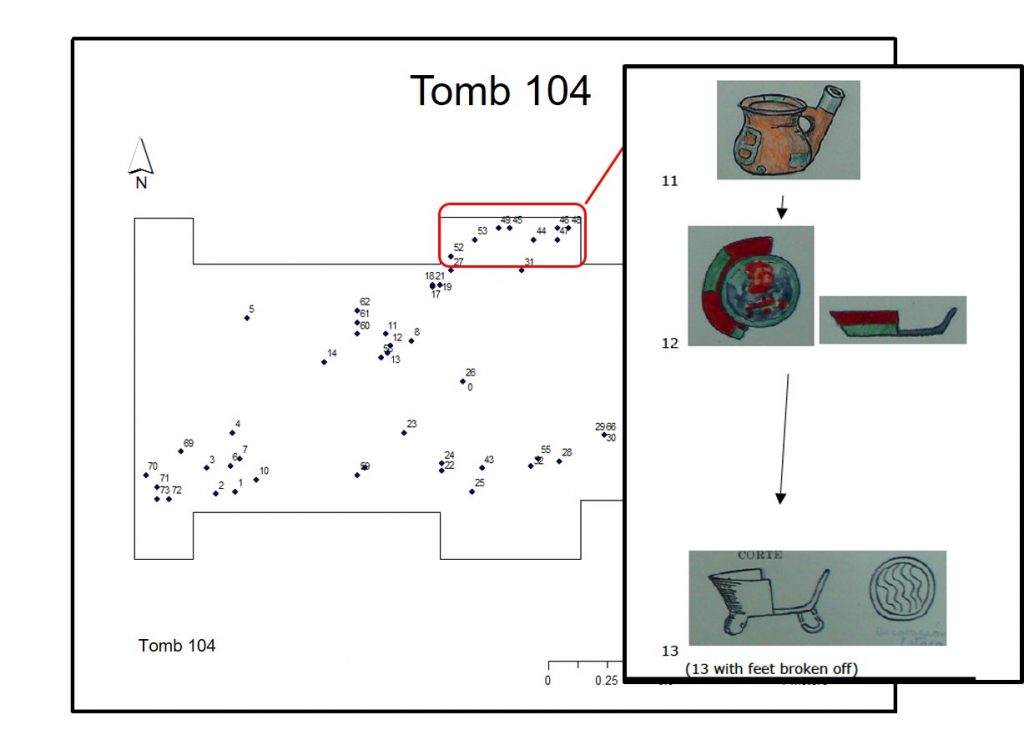

The project that the collaborators undertook grew out of Hoobler’s dissertation research focused on tombs of the site of Monte Albán in Oaxaca, southern Mexico, built by the Zapotec peoples of the area from ca. 500 BCE–850 CE (see Figure 1, and Hoobler 2011 for more information). The tombs had never been fully published by their excavator, the archaeologist Alfonso Caso. During extensive archival research, Hoobler discovered and then digitized a trove of some 8,000 catalogue cards made by Caso and his collaborators in the 1930s and ‘40s. The cards detailed the position of all the objects Caso and his collaborators had excavated from a given tomb in centimeters from the back and side walls of the tomb (see Figure 2). (At the time Caso was working, all objects were removed from the tombs and ultimately sent to the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.) Using these cards, Hoobler created two-dimensional diagrams of the tombs for her dissertation (see Figure 3). At the time when she finished graduate school at Columbia University in the Department of Art History and Archaeology in 2011, the free 3D modeling program Google Sketchup (now Trimble Sketchup) did exist, but there was no training and certainly no mandate for working on software for graduate students in art history at that time.

Figure 1: Large open plaza of archaeological site of Monte Albán.

Figure 2: Large index card with typed information about an object.

Figure 3: Simplified diagram of floor plan of a tomb with side niches. Numbered dots on plan show location of objects.

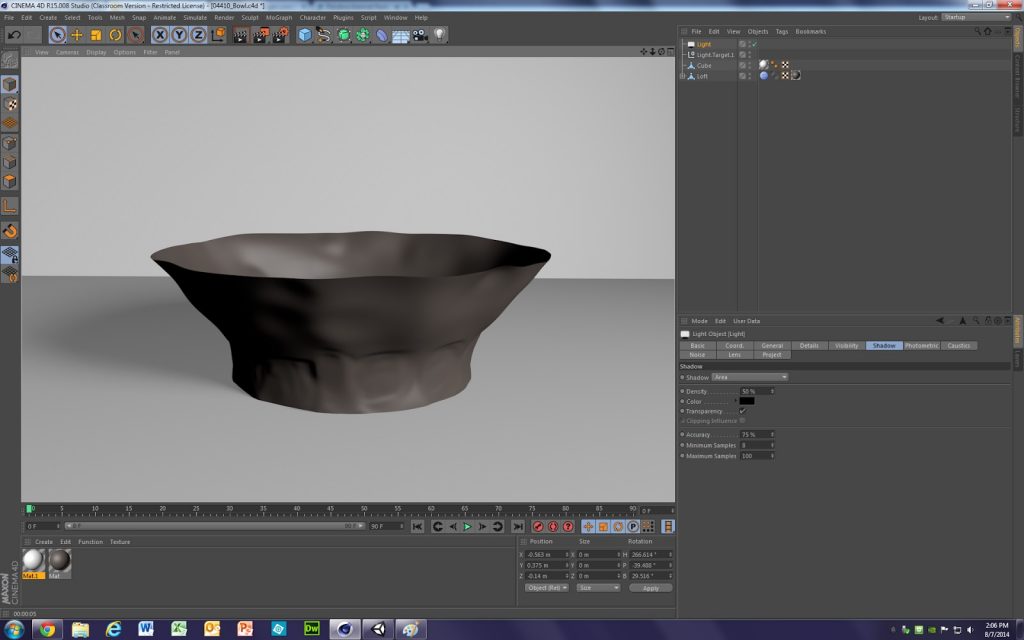

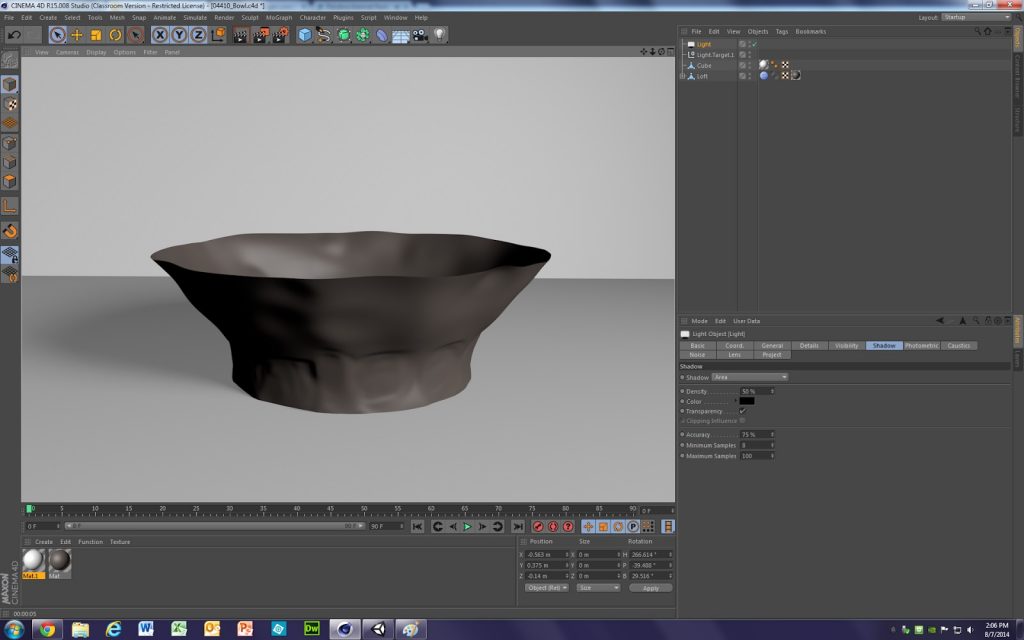

In summer 2013, after becoming an Assistant Professor at Cornell College in Iowa, Hoobler attended an NEH Advanced Topics in the Digital Humanities Summer Institute on Humanities Heritage 3D Visualization: Theory and Practice,[4] where she experimented with some of the many tools by then readily available, free or at low-cost, to those interested in 3D modeling. Based on working with the University of Arkansas’s dedicated, well-funded, and well-developed Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies (CAST) lab,[5] Hoobler’s original, perhaps overly ambitious goal for the project was fully product-based: to allow users a phenomenological experience of one of these burial chambers by creating a virtual tomb, including all its contents, with which the user would be able to interact. This goal proved unattainable during the two summers of work because it required computers with much greater computing power than were available on a typical small liberal arts college campus. Furthermore, such a project would have required much greater technological skill on the part of Hoobler and probably thousands of hours of work on the part of the team. Still, a great deal of progress was made. Not only did all participants learn a great deal about working with 3D modeling software (including Maxon Cinema4D), the process was enlightening in regard to the important role that 3D scanning and modeling might play in cultural heritage in the future. From a scholarly standpoint, it was very clear to Hoobler that the process of modeling the tomb and its contents, and virtually placing them, allowed—and even forced—the modeler to engage in the art-historical technique known as close looking in dealing with the objects. Experiencing this process also made apparent many characteristics of the burial chambers that the creation of two-dimensional diagrams had not.

Based on the NEH Summer Institute training, Hoobler sought and received grants from Cornell College and the McElroy Fund/Iowa College Foundation for Ve’Amber Miller and Catherine Quinn to work with her in summer 2014.

Ve’Amber Miller (Cornell College ’15) comments:

“As an Archaeology major—and someone who already had an interest in how to engage technology with the past—there was no hesitation in wanting to join this team. At first it was daunting even as I was going into my final year of undergraduate studies because I did not have experience in 3D modeling, but over the course of our work I found the support from everyone and the story these artifacts told was more than enough to push me through. Being able to place the items that had been recreated back into a virtual tomb made the history even more real; 3D printing those same objects–some that had been destroyed decades ago–so that others could hold them in their hands made it more real for them as well. The most important thing is that I learned from this project, and will only do better in the future so that history becomes an interactive and engaging experience for everyone.”

As of this writing, Miller is working as a Park Guide at the Pullman National Monument in fall 2017. Prior to working in this position, she worked at Weir Farm Historic Site, where she put her skills and experience acquired during this project to use in creating a virtual gallery of art[6] and an ESRI StoryMap based on “Julian Alden Weir’s Student Years in Europe,” using digitized documents and artifacts from Weir Farm’s collection.

Her collaborator that summer, Catherine Quinn, Cornell College ’15, was an art history major who had been interested in technology for years, having gained experience through graphic design courses in high school and customizing a gallery website while interning at the Center on Contemporary Art. Quinn said:

“Working on this project with Dr. Hoobler was exciting for a number of reasons. It was one of the first opportunities I had as an art history major to apply what I had learned in the classroom while contributing to a real world, ongoing, body of research. In addition, I was able to combine multiple fields of interest (art history and technology) while being introduced to others (archaeology), and building extensively on my existing knowledge through hands-on learning. Finally, being able to work on this particular site was especially meaningful due to the fact that we were working with the intention of offering our research to the Community Museum in Oaxaca. As one of my first forays into ‘digital humanities,’ this project has left me inspired by all the ways I see technology providing not only new insight but also accessibility to people, and I foresee it having a beneficial influence on how we curate museum collections, design interactive exhibits, and present research.”

Quinn is currently based in Seattle and applying for graduate programs in digital cultural heritage and related disciplines.

That first summer, predictable challenges ensued. The software had been updated between 2013 and 2014 and many functions had changed. In addition, due to the vicissitudes of funding, the two students were starting at different times, with Miller beginning several weeks after Quinn. Thus, Quinn and Hoobler struggled together with the Maxon software, and Quinn largely trained herself on the finer points of working with it, using tutorials and message boards she found on the Internet. Quinn then trained Miller when she joined the team. (One counterintuitive point about working with students on summer research is that it is much easier to have two or perhaps three students working in collaboration: when there is a question on how to do something, they work through it together, usually showing their professor how to do it once they have figured it out.)

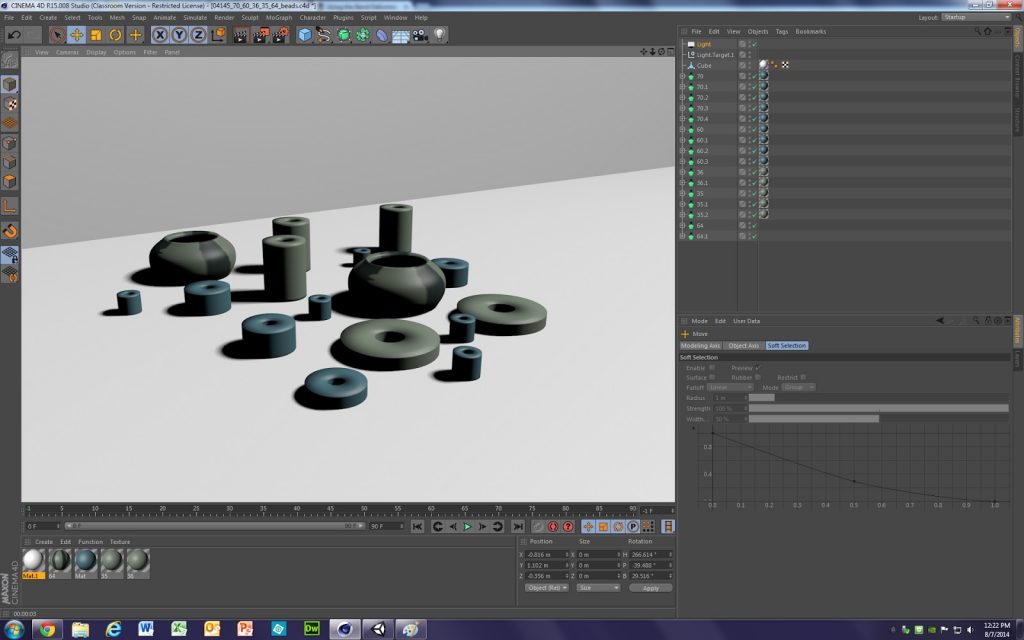

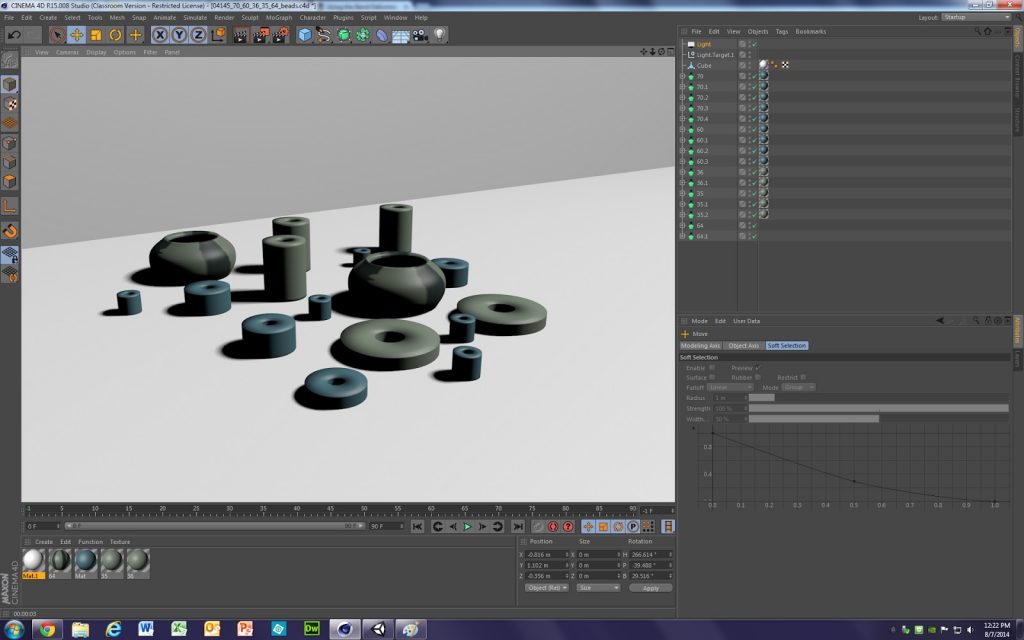

Miller, Quinn, and Hoobler then worked through the challenges of free-hand modeling of objects illustrated in profile on the catalogue cards (see Figures 4 and 5). This was exciting work, since some of the objects shown on the cards were made out of unfired clay or stucco and apparently were destroyed in transit to Mexico City. For this reason, many of the objects documented in the tombs cannot be found in the warehouse of the National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. Thus, while virtual, these proxies, derived from catalogue cards, are the only place where these objects “exist” in the world.

Figure 4: Screengrab showing the Maxon Cinema4D software program with a bowl modeled in the active window.

Figure 5: Screengrab showing the Maxon Cinema4D software program with a stone beads modeled in the active window.

While a broader discussion of the theorization of replicas is beyond the scope of this article, two points are worth noting. One is regarding copyright issues. Unlike a project involving modern or contemporary art or creations, the objects found in tombs were created over a thousand years ago and have no clear author whose descendants could be traced to seek permission for the replication. Even if one considers the archaeologist Alfonso Caso who led the team that conducted the excavations as the author of these objects, these were “reactivated” some 70–80 years ago. The National Museum of Anthropology and History might also assert its rights to the objects, since it is their physical repository. However, as per the College Art Association’s Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts, the modeling of such works would be well within the furthering of “… the teacher’s substantive pedagogical objectives,” as described in Section Two, Teaching About Art (College Art Association 2015, 10).

The second point has to do with the ontological status of the replica. Many scholars have written eloquently about replication, that moment “when ideality and reality touch each other,” as the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard put it (Kierkegaard 1983, 131). Probably the most influential text on this topic is Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Benjamin discussed in depth the concept of authenticity in copying works of art, arguing that there is a unique authority to the original that he called its “aura,” which would be dissipated in an age of mechanical reproduction (Benjamin [1935] 1968, 224). However, given the number of visitors to the Louvre yearly, it seems the elusive aura has not withered away, but is never inherent to a copy no matter how perfect its mode of replication. Scholars have generally asserted that the original work of art will not be replaced by digital facsimiles, and in fact these copies may increase the desire to experience the original (Hall 1999, 277; Cuno 2014). The topic of replication will continue to be the subject of debate and discussion in art history. However, the team was working from originals that in many cases were ceramic vessels mass-produced in workshops, minimally decorated and similarly sized and shaped for stacking and transport, and thus fit much more easily within the sphere of “visual culture” than fine art. Therefore, such questions, while fascinating, are less relevant to the argument at hand.

Moving from Process to Product: Manage Your Expectations

During the process of making the models, students and teacher alike were learning many skills. Some of these were art historical. Many art historians have described art history, like many other humanities disciplines, as having a toolkit of methods from which to choose rather than a prescribed set of steps to follow as in the sciences (Long and Schonfeld 2014, 10). In general, art historians’ methods are informed by the kind of research questions they seek to answer, which may vary depending on their project. Three methods used for this project were close looking, library and archival research, and a contextual analysis methodology. Close looking, or viewing and analyzing objects through very close and sustained study is the basis of connoisseurship and authentication as well as formal and iconographic analysis. Even with objects of the type that the team were working with (i.e., bowls and stone objects made by anonymous artisans hundreds of years ago), patterns and insights about them emerge through careful looking. Small wonder then that many art historians also execute their own illustrations, and many seasoned professors encourage their students to draw works in order to commit their contours to memory. The use of 3D modeling demands a similar quality of focused attention to replicating an object or space, although one is now “drawing” with a mouse rather than a pencil. Since the team was working largely from photographs of catalogue cards, it was very important for all concerned that the students were able to see originals of the kinds of objects being modeled, even if not necessarily the exact work, at the Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca, Santo Domingo, in Oaxaca City during the research period.

In terms of archival research, while there was no time to do additional research since so little of this material has been digitized, students had to dig through several large and unwieldy archaeological publications published in Spanish in the 1950s and ‘60s. This acquainted them with basic but less-discussed principles of archival research such as figuring out which sections of the text were essential to translate versus those that could be skimmed.

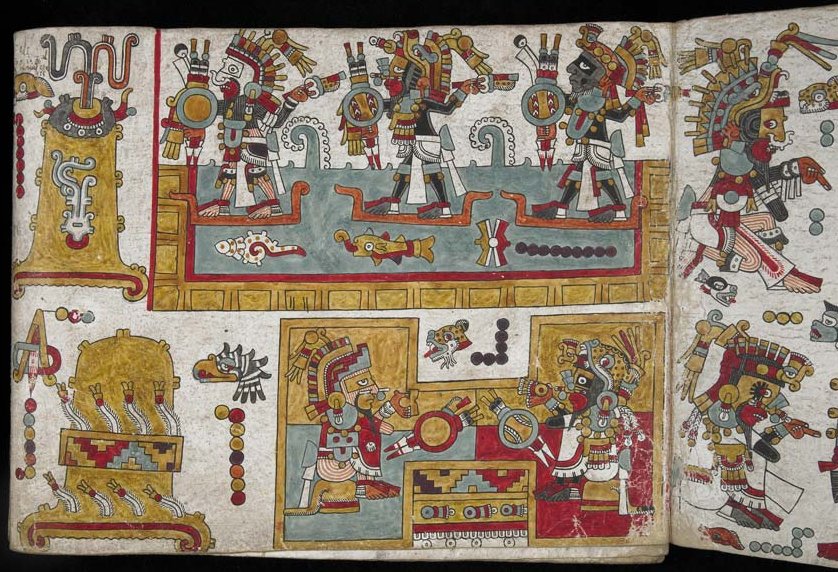

Finally, the team was certainly undertaking a contextual analysis of the tombs, trying to understand the original placement (and by extension, use) of the objects in these spaces. All the collaborators discussed how these tombs were in a sense similar to ritual caches excavated and documented by Leonardo López Luján at the Aztec Templo Mayor in Mexico City. There, López Luján has been able to show how the intentional deposition of objects in a specific sequence in different parts of the site was the result of ritual actions undertaken in support of concrete purposes related to propitiation of the gods. Yet, the Zapotec case is less clear, given that tombs were filled some seven centuries or more before the invasion of the Spanish, and deities worshipped in one way in the sixteenth century may have been venerated in an altogether different one centuries earlier. However, reconstructing the tombs and their contents does bring us closer to understanding the lives of ancient peoples that we know comparatively little about.

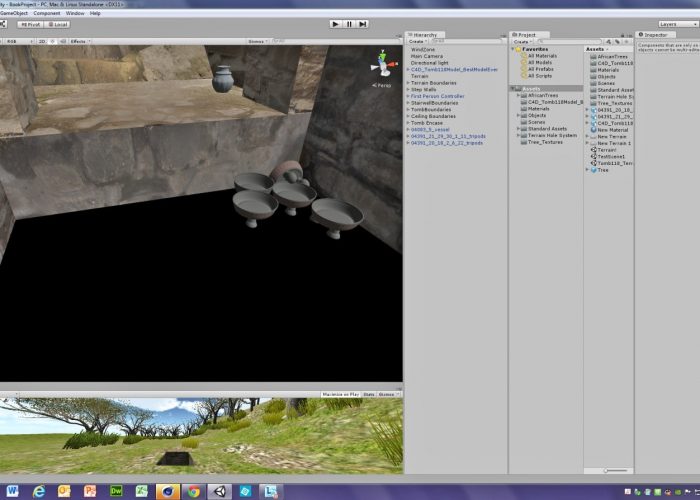

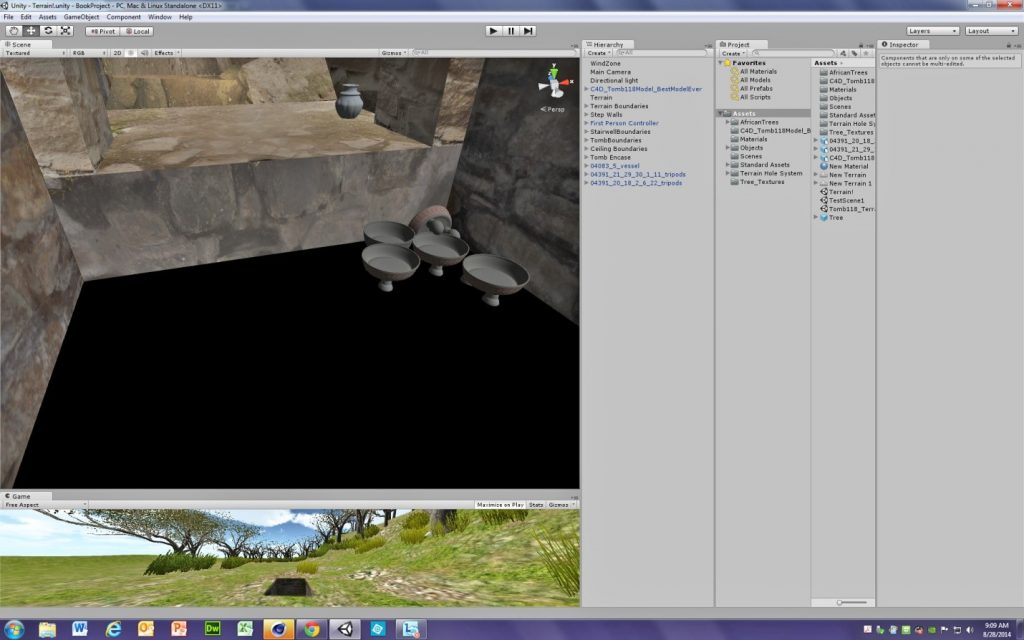

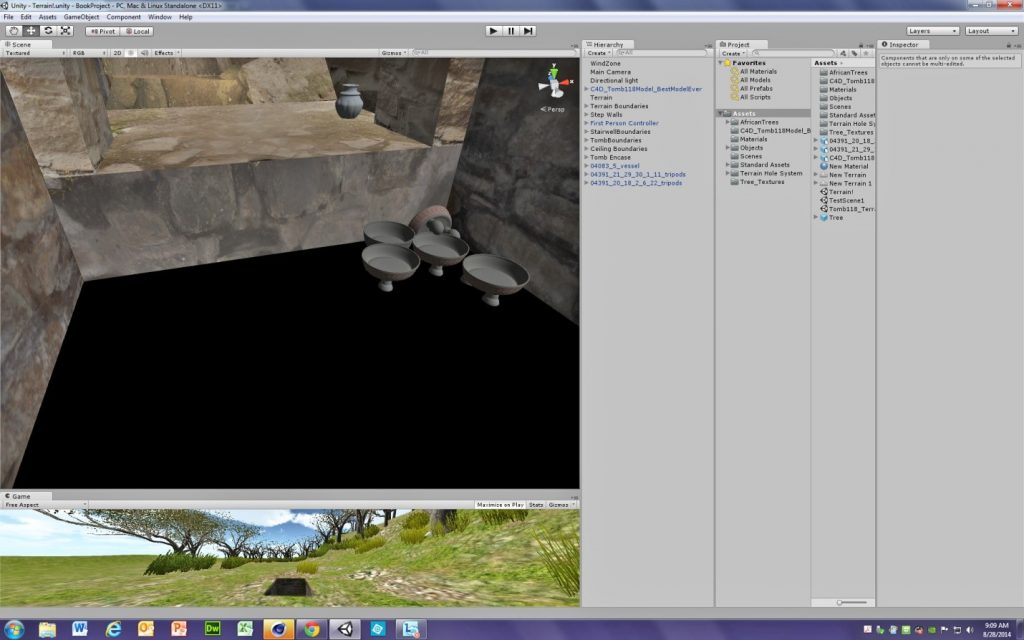

While the processual byproducts related to art history were quickly realized, the products were not. The original plan was for the objects in the tomb to be modeled in Maxon Cinema4D, the tomb itself would be built in the Unity game engine software, and then, the object models would be imported into the tomb.[7] However, the version of Unity we were working with was not compatible with webGL, becoming difficult to view on most browsers shortly after the model was created, a frustrating but very common experience in digital humanities projects.

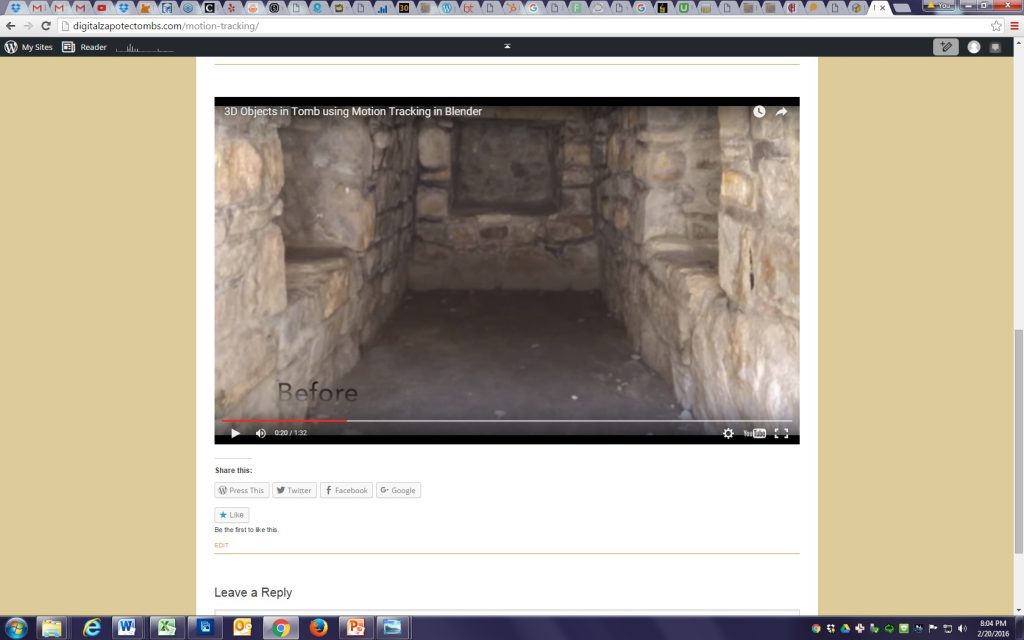

Quinn did in fact create a very satisfactory model of the tomb in Unity, but at this point, more challenges emerged. While the resulting models of the objects in the tombs were excellent, their high resolution meant that there were no on-campus computers that could handle both the tomb model as well as the virtual versions of all the objects in the tomb. Later, in summer 2015, Arturo Hernández modeled objects in the same data-heavy manner, but then realized that the models could be made workable by removing details not obvious to the naked eye. The team determined that it should have more carefully sought out a best practices statement for getting around the issue of large file sizes (see Figure 6 and online gallery[8]). Ultimately, Quinn was able to determine how many objects could be loaded into the model so that the digital reconstruction could be interacted with without crashing the program. Reaching this more process-based objective provided us with a better understanding of how the interior of tombs were illuminated. Unity allows the user to move the sun across the sky, and although previous scholars had insisted that there was almost no illumination in the tombs, and that the Zapotecs would have had to use torches (Martha Carmona Macías 2007, personal communication), the virtual model made it clear that for much of the day there was sufficient light in the tomb for mourners to conduct simple rituals. In the future, a more complete model that takes into account the height of ancient house walls might disprove this idea, but for now, it seems likely that rituals might have started during the day. The Unity model also had the benefit of offering a product, a kind of “proof-of-concept” for the whole project. Even with the thoroughly modern, overall-clad default Figure Unity offers for interacting with the scene (no stock characters fit for ca. 300 CE Mesoamerica, surprisingly!), there was invariably a great deal of interest and admiration for the video of the tomb as modeled in Unity. This shows how important it is to build in some degree a visual aid, particularly in art history.

Figure 6: Screengrab showing the Unity game engine, with several panes open.

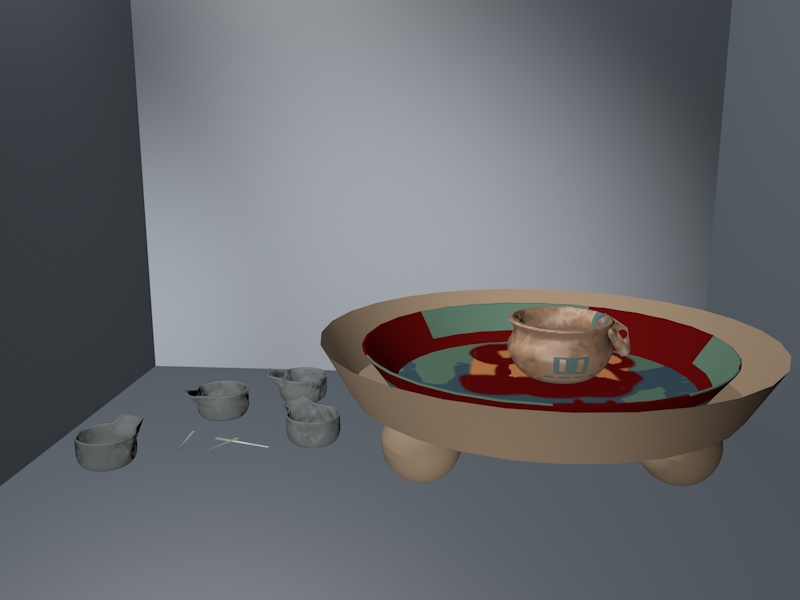

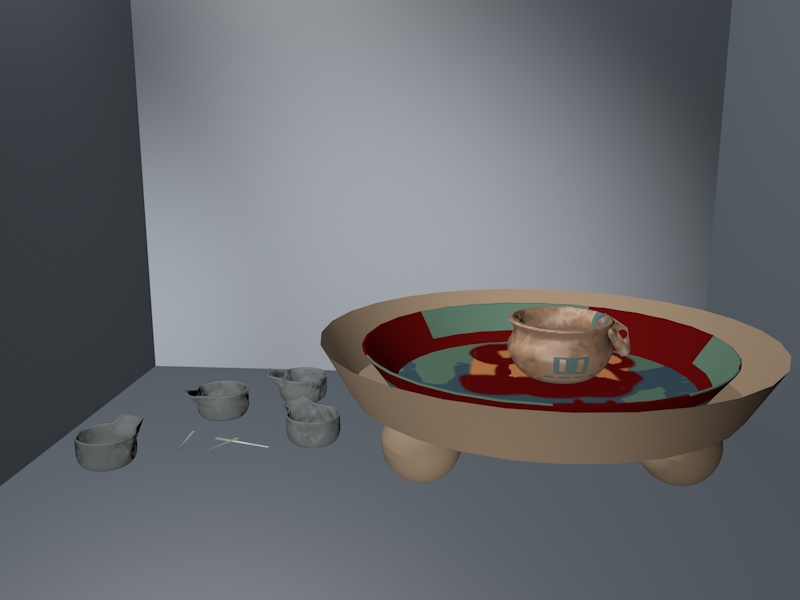

Miller also completed a section of one of the tombs as a final iteration of the project during an independent study with Hoobler. When she made the original 2D tomb models, Hoobler noted that objects of particular importance were placed in niches in the side and back walls. It was particularly important to try to visualize these privileged spaces, yet the diagrams Hoobler produced in 2011 were extremely crude (see Figure 7). During the summer, Miller and Quinn modeled perhaps the most curious and unusual object that was dealt with, a hardstone “billy club” found in one of the niches of Tomb 118 that is extremely atypical of the tombs. In a later independent study, Miller continued work on shedding light on the niches. In particular, she 3D modeled an entire niche of a different tomb, Tomb 104, which held quite a few of the most elaborately decorated ceramics from the site. Some of these were plates, but others were odd pitcher-like vessels. Miller accomplished a great deal with this, even giving their surfaces the appearance of the painted glyphs that were present on these vessels. Despite the imprecise information on the catalogue cards related to this space, Miller was able to generate decent models for the bone needles likely used for ritual bloodletting that were found in conjunction with the vessels. The much more naturalistic representation of the niche that Miller was able to generate is the product from these projects that is most easily transferable to traditional scholarship about the Zapotec (see Figure 8).

Figure 7: Simplified diagram of floor plan of a tomb with overlaid diagram of niche.

Figure 8: Realistic image of a niche within the tomb, showing several vessels inside of it, some brightly painted.

Both of these examples show how important it is to have realistic ideas and goals of what can be produced in a single summer, particularly by people who are new to working with the software in question. Upon reflection, it is clear that it was unrealistic to expect that the team could model a whole tomb and 30+ objects as well as make such a model interactive and functional. However, even if the original goal to have a highly detailed model containing all the objects from that tomb was not achievable, three significant products were created: models of individual objects; a mimetic model of a portion of a tomb holding iconographically rich materials; and the modeling of an interactive tomb, albeit without many objects in it. Additionally, a tremendous amount was learned with regard to the development of processes that can result in better products in the future (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Screenshot of a video, marked “Before” at lower left, and showing an empty stone chamber.

Projects are Iterative–But Preparation Is Crucial

In Summer 2015, Hoobler teamed up with Arturo Hernández, Jr. (Cornell College ’16), a studio art and computer science double major. Arturo commented that:

“I joined the Digital Humanities Zapotec Tomb Project because I was thrilled about learning how to use new pieces of software and hardware; additionally, I wanted to further explore and learn about my culture and heritage. This project and team allowed me to contribute ideas and learn more about the importance of digitizing artifacts.

I woke up always looking forward to creating objects and exploring different techniques during the process, as well as researching different applications. One of the rewarding feelings was seeing results from 3D printing some of the objects and analyzing their past or their functionality.”

Before starting his research with Hoobler, Arturo had taken a computer graphics class where he programmed some tools for a small 3D modeling program. Consequently, going from dealing with back-end to user-end 3D space helped him to see the bigger picture of 3D applications. Since graduation from Cornell, Hernández has continued to be involved in projects related to technology and Latin America. He worked for a year at Abriendo Mentes, a non-profit organization, teaching basic computer skills to rural and underserved populations in Costa Rica. He is currently based in Los Angeles and is getting further computer training and certification to continue in technology, ideally with a focus on international work.

Hernández learned the software extremely quickly. He was able to model asymmetrical and eccentrically shaped pieces very effectively, and ultimately was able to solve one of the most difficult problems of the previous year: the question of how to add multiple objects into a virtual tomb.

This came about partially by chance and completely on Hernández’s own initiative. In summer 2015, the funding for Hoobler and Hernández to work together came through the Cornell Summer Research Institute (CSRI) sponsored by Cornell College, which offered newly formalized ways for students and faculty to collaborate, with students receiving various opportunities to showcase their work to participants from across all departments. In one workshop that included Professor of Physics Derin Sherman, Hernández explained the problem with the models, which could not hold the digital models of vessels and be interacted with, for the file size became unmanageable for any computer on campus. Sherman commented offhand that perhaps Hernández could just use video software to make the concept clear, as Sherman had done to make a particular physics concept more understandable for students. This sparked Hernández’s imagination, and after some research, he found Blender,[9] a free, open-source software that allows for importing models and video and integrating them together in a process known as motion tracking. This can be seen online,[10] or in Figures 10 and 11. However, even though initial use of the Blender software suggested a possible way to work with the tombs, prior planning was still necessary to use this new tool in the most productive way.

Figure 10: Screenshot of a video, marked “After” at lower left, showing a stone chamber with small ceramic figures and vessels inside.

Figure 11: Young man with a camera kneels by a table with several plastic objects on it, taking a photograph of them.

Technology and Community Engagements: 3D Modeling to Printing

It is important to note that the precise limits of the site of Monte Albán were in fact set in the 1930s by several towns surrounding the core of the site, each of which donated some of their communal landholdings to create an archaeological zone. As a result, there is an inherent conflict, even putting aside all national legislation, as to how the artifacts of Monte Albán might be shared simultaneously with all these communities. This includes villages further out from the site’s core, which in ancient times helped to make some of the vessels and other offerings found in the tombs. It is possible, as has been discussed by other scholars, that digital versions of heritage objects might offer the possibility for their sharing by different stakeholders. (This has been discussed in various articles from a 2012 issue of the Journal of Material Culture, particularly Brown and Nicholas 2012 and Newell 2012 as well as Bell et al., Hennessy et al., and the entire 2013 special issue of Museum Anthropology Review titled “After the Return: Digital Repatriation and the Circulation of Indigenous Knowledge.”)

One of the ultimate goals for work on the tombs has been to return, at least virtually, some of the material culture of Oaxaca taken from the state’s small communities after the archaeological excavations of the 1930s. It was during this period that most of the excavated objects were sent to the warehouses of the National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. As a response to this loss of their local culture, since the 1980s some of the towns have sought to keep this kind of material from leaving their towns by creating local community museums (Hoobler 2006). While efforts to create virtual versions of the community museums had been discussed by the team in summer 2014, it was ultimately not undertaken. However, because Hernández is fully fluent in Spanish and fully bicultural with knowledge of Mexican and even specifically Oaxacan culture, a community engagement component could be added during the 2015 portion of the project.

Interested in testing these possibilities, Hoobler decided that she could make a test case for virtual sharing with one community by working with the Community Museum of the town of San Juan Guelavía close to Oaxaca City. Knowing that a large segment of the town’s population was fluent in Zapotec languages and/or English, (the town has had a large number of migrants to the United States, see Cohen and Browning 2007), Hoobler decided to offer some materials that might help facilitate increased understanding of the ancient ancestors of the Zapotecs. Such materials included coloring sheets with line drawings of actual ancient vessels. Hernández created trilingual Zapotec-Spanish-English game boards for a version of the Lotería game that is similar to Bingo, but with images and words. Hernández also created models for and supervised the 3D printing of replicas of artifacts found in the tombs (see Figures 11 and 12), including some plastic vessels, “ear flares,” ornaments like those made of jadeite found in the tombs fitted with clip earring backs, and an incense burner. This last object was particularly satisfying because when Hernández and Hoobler visited the community museum, they found a case holding actual pre-Columbian objects found in the town. It included the handle for such an incense burner, but the bowl of the burner had been broken off. (See Figure 13 for a contrast between the ancient and modern objects.) This 3D model was an object that young people in the town could actually handle without fear of causing it damage, allowing them to understand better the purpose of a formerly innocuous object in their museum.

Figure 12: Closer view of the table in figure 11, showing different 3D printed objects, including vessels and small figurines.

Figure 13: Photograph of a display case with a glass top, and ceramic fragments inside. Inset with second image, a plastic vessel similar to one of the ones seen inside the case.

While this was a gratifying episode, the interaction largely ended there because Hoobler had not undertaken long-term planning for a continuous relationship with the museum. There had been discussion between Hernández and Hoobler at the beginning of the summer about training young people in the community to work with digital 3D modeling themselves, but as it was unclear at that point what the capabilities of the computer at the community museum were, this idea was discarded. However, as Pohawpatchoko et al. (2017) discuss, this would likely be the richest option for receiving useful input regarding the value of reproducing ancient objects for the community. As has happened in past collaborations with indigenous groups, there were “good intentions” on the part of the North American university team but not many actual solutions (La Salle 2010). Community engagement is incredibly rewarding, but can be difficult or feel awkward when not executed within a longstanding relationship. Without an already-established personal relationship with the town and community museum committee, this attempt was limited in its success. However, this experiment provided Hernández with valuable experience working with local communities that he would use in his subsequent work in Costa Rica, a project that did prove to be more successful.

This episode brings up a final point about 3D modeling and its use in art-historical scholarship and teaching. It can be an end unto itself, and as the price of 3D printers becomes more affordable, it can be used in conjunction with 3D printing effectively. This is helpful information in many ways. First, it allows us to rethink traditional methods of studying art. Within art history, primacy has been given to the visual qualities of a work of art, yet sculpture and many objects were very much prized for their tactile qualities as well. Theoretically, 3D modeling and 3D printing would allow students to recapture some of the tactile experience of an object. There may be some exceptions—one being that the tomb modeled by Miller in 2014 was particularly hard to model with digital means since it had asymmetrical walls that curved irregularly; yet those walls also referenced the fingers that had shaped it (see Figure 4). Thus, though it was printed in plastic filament on a CubePro printer and the fine-grained texture was in no way accurate, in general terms even the plastic proxy in some way called attention to the hands that had shaped it. Unfortunately, in practice, many smaller schools are not buying the kind of high-end 3D printers that can print texture similar to that of the original and, at larger universities, there is sometimes a siloing of resources, with the result that “less technological” departments such as art history might not be able to use this sophisticated equipment, whose raw materials are similarly quite costly.

Secondly, 3D modeling and printing gives students a sense of the scale of objects when they are printed at full size. Just as viewers of the Mona Lisa are always surprised by how small the painting is, it is also helpful to understand, in a phenomenological sense, the contents of tombs at a human level. For example, in summer 2015, one of the objects given to the community museum was a “mystery vessel” found in several of the tombs. (See gray object at left of Figure 13.) Its side walls are so low that it is hard to imagine what it could have been used for—it is not an incense burner or other easily recognizable artifact. The hope in giving it to the community museum was that an older member of the community might recognize it, as has happened previously (Lind and Urcid 2010, 276–77). However, because low-end 3D printers are usually only capable of printing objects that can fit within a 10” square, it is nearly impossible to recreate the sense of scale one experiences from a huge pre-Columbian olla jugs. Low-end printers also create plastic objects that are aggressively monochromatic and very toy-like. More sophisticated, expensive printers can generate objects in materials such as ceramic, metal, or paper with very delicate tints mimicking the original object, but lower-end printers create models that look very Lego-like (Figure 13) and can even run the risk of seeming disrespectful when working with cultural heritage objects.

The Importance of Reflection in the Process

Since Hoobler originally conceived of the project as more product-based and was focused on the end result, she had not built in as much time and opportunity as she later would have wanted for self reflection on the part of the students (or herself). This is important on the one hand because it is increasingly clear how metacognition, or reflecting on the process of learning itself, is crucial to learning. Self-reflection is helpful for a number of reasons. First, as Paige Morgan notes, it allows participants to broaden the question of whether a project is “done” beyond a yes/no binary (Morgan 2014). A team can recognize and acknowledge progress even if they do not realize all that they plan to do. Second, progress can be measured in real time, perhaps weekly. Since digital work is new for many professors, they may find that they were optimistic about what the team can accomplish in the time allotted. Third, writing and documentation may help explicitly describe and justify the choices made at different points where available data may not be available.

Interestingly, although self-reflection was not structured as part of the project, all the students sought out the opportunity to reflect on the process and showcase their work. Miller created a website for the project (www.digitalzapotectombs.com) that Hernández added to and Hoobler has maintained. Professors who work with undergraduates on academic projects should provide them with this opportunity, which allows them to keep track of how they arrived at certain solutions, maintain a record of challenges they have surmounted, and chart the progress they have made. A website or other public venue also allows them to have a permanent record of their work, accessible by potential employers or graduate school admissions personnel. In general, professors should build this kind of periodic reflection into the project timeline, perhaps by encouraging blogging. This would allow the students (and the professor) to reflect more effectively on how much progress they were actually able to make in a single summer, semester, independent study period, or over the course of a longer-term project.

Despite not keeping an ongoing record of progress in a blog format, the lessons learned by both the students and the professor throughout the process are evident. Working collaboratively with peers from such diverse fields meant each team member was able to bring their own set of skills and background knowledge to the project, and that others were able to learn from them. By extension, cross-disciplinary relationships were formed with other students and staff on campus as well as at other institutions as they were brought in to consult on various issues. Hernández, Miller, and Quinn were able to take ownership of their contributions to the project, each utilizing their “very particular set of skills,” and working more as collaborators with Professor Hoobler. Hoobler would argue that it was a good and productive experience for the students to see their professor not as the “sage on the stage” but as a coworker, not infallible— sometimes not even the authority on the project. All participants saw first hand how important project management and planning skills are, and yet how one discrete portion of a project can be completed in a relatively short time.

Why Use 3D Modeling in Art History?

To conclude, there are many affordances of 3D modeling for art historians. Current modeling technologies allow for what Johanna Drucker has called digitized, rather than digital art history, the latter being defined as “analytic techniques enabled by computational technology” (Drucker 2013: 7). The use of 3D modeling is the digital equivalent of sketching the objects you are studying—it forces sustained close looking and a quality of focused attention to representing a given object or space. However, it does obligate you to be much more concrete than sketches are in representing your understanding of the physical context of objects and buildings as you think through their placement and surroundings, sometimes including terrain, neighboring structures, etc. This type of modeling is particularly helpful for considering ancient spaces where context is unclear: a 3D environment allows the scholar to reunite fragments that are lost, dispersed, or damaged. When printed, 3D models also afford the user a physical object that gives them the experience of scale and basic tactile qualities, opening up questions of use and function for mystery objects. As technology for 3D printing continues to improve, 3D printing will likely also offer a very close proxy for the object in terms of colors and textures.

However, the pedagogical benefits of 3D modeling projects may actually outweigh these digital “products.” The opportunity for students to form close working relationships with each other and faculty in a setting where their professor is not an infallible authority and they may well have to “teach the teacher” at points is important. In this particular case, students also gained valuable international experience, confronting cultural differences and communication barriers at times. In general, students learn about and then grapple with thorny problems to which there are no easy solutions. It is important that they complete at least one aspect of the project, perhaps a prototype that can act as a future “calling card” for them, and ideally it should be part of a broader process of reflection on the project. Such a “proof of concept” has broader pedagogical value too—the professor can then use it in their classes, discussing how it was made by students, and making such processes feel manageable and “relatable” for other students.

Of course, the main takeaway of this article for professors is to choose incredibly smart, positive, conscientious students who are much better than you are with software as your collaborators and then—just get out of the way. Your students will find ways to take ownership and make the project, or at least parts of it, happen in ways you never expected, but which will teach you about technological (and other) solutions you never dreamed existed.

Bibliography

Bell, Joshua, Kimberly Christen and Mark Turin. 2013. “Introduction: After the Return.” Museum Anthropology Review, special issue “After the Return: Digital Repatriation and the Circulation of Indigenous Knowledge” 77, nos. 1–2: 1–21.

Benjamin, Walter. (1935) 1968. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn, 217–51. New York: Schocken.

Brown, Deidre, and George Nicholas. 2012. “Protecting Indigenous Cultural Property in the Age of Digital Democracy: Institutional and Communal Responses to Canadian First Nations and Māori Heritage Concerns.” Journal of Material Culture 17, no. 3: 307–24.

Cohen, Jeffrey, and Anjali Browning. 2007. “The Decline of a Craft: Basket Making in San Juan Guelavía, Oaxaca.” Human Organization 66, no. 3: 229–39.

College Art Association. 2015. “Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.” February 2015. Accessed November 25, 2017. http://www.collegeart.org/pdf/fair-use/best-practices-fair-use-visual-arts.pdf.

Cuno, James. 2014. “Beyond Digitization—New Possibilities in Digital Art History.” The Iris: Behind the Scenes at the Getty (January 29, 2014). Accessed November 1, 2017. http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/beyond-digitization-new-possibilities-in-digital-art-history/.

Drucker, Johanna. 2013. “Is there a ‘Digital’ Art History?” Visual Resources: An International Journal of Documentation 29, nos. 1–2: 5–13.

Hennessy, Kate, Natasha Lyons, Stephen Loring, Charles Arnold, Mervin Joe, Albert Elias, and James Pokiak. 2013. “The Inuvialuit Living History Project: Digital Return as the Forging of Relationships Between Institutions, People, and Data.” Museum Anthropology Review 77, nos. 1–2: 44–73.

Hall, Debbie. 1999. “The Original and the Reproduction: Art in the Age of Digital Technology.” Visual Resources 15, no. 2: 269–78.

Hoobler, Ellen. 2003. “‘To Take Their Heritage In Their Hands’: Indigenous Self-Representation and Decolonization in the Community Museums of Oaxaca, Mexico.” American Indian Quarterly 30, no. 3: 441–60.

———. 2011. “The Limits of Memory: Alfonso Caso and Narratives of Tomb Assemblage from Monte Albán, Oaxaca, Mexico, 500–800 and 1931–49 CE.” PhD diss., Columbia University.

La Salle, Marina J. 2010. “Community Collaboration and Other Good Intentions.” Archaeologies 6, no. 3: 401–22.

Lind, Michael, and Javier Urcid. 2010. The Lords of Lambityeco Political Evolution in the Valley of Oaxaca During the Xoo Phase. Boulder, Co.: University Press of Colorado.

Long, Matthew P., and Roger C. Schonfeld. 2014. “Preparing for the Future of Research Services for Art History: Recommendations from the Ithaka S R Report.” Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 33, no. 2: 192–205. doi:10.1086/678316.

Morgan, Paige. 2014. “How to Get a Digital Humanities Project Off the Ground” (June 5, 2014). Accessed November 1, 2017. http://www.paigemorgan.net/how-to-get-a-digital-humanities-project-off-the-ground/.

Nagata, Wayne, Hera Ngata-Gibson and Amiria Salmond. 2012. “Te Ataakura: Digital Taona and Cultural Innovation.” Journal of Material Culture 17, no. 3: 229–44.

Newell, Jenny. 2012. “Old Objects, New Media: Historical Collections, Digitization and Affect.” Journal of Material Culture 17, no. 3: 287–306.

Pohawpatchko, Calvin, Chip Colwell, Jami Powell and Jerry Lassos. 2017. “Developing a Native Digital Voice: Technology and Inclusivity in Museums.” Museum Anthropology 40, no. 1: 52–64.

Snyder, Lisa M. 2012. “Virtual Reality for Humanities Scholarship.” New Technologies in Medieval and Renaissance Studies 3: 396.