Introduction

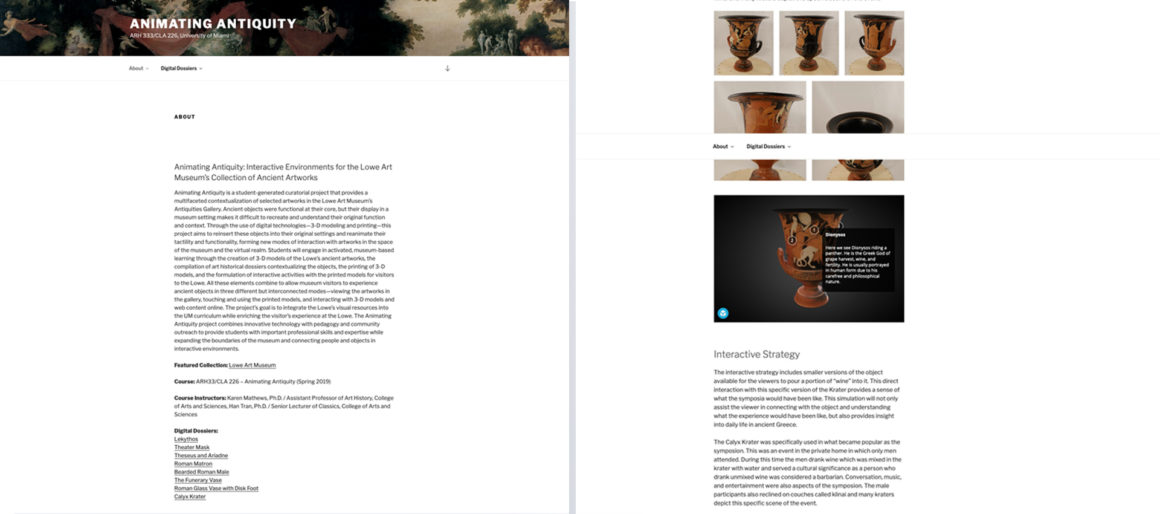

The Animating Antiquity Project was funded by a CREATE grant from the Mellon Foundation, whose aim is to foster the connection between students and cultural resources on the University of Miami campus (University of Miami Libraries and Lowe Art Museum 2019). The project was implemented in an interdisciplinary course, Greek and Roman Art (ARH 333P/CLA226P), co-taught by Professors Karen Mathews (Art and Art History) and Han Tran (Classics) in the Spring Semester of 2019. Twenty-one undergraduate students in the course undertook a curatorial project to recontextualize eight ancient objects in the Lowe Art Museum at the University of Miami, using various digital technologies to recreate and understand their original function and context (Lowe Art Museum 2019). Students devised multifaceted ways of reanimating antiques for visitors to the Lowe; research dossiers provided information about the function, context, and historical background of the objects, 3D digital models allowed viewers to manipulate the artwork and experience it in the round, 3D prints incorporated the elements of tactility and interactivity, while augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) experiences inserted the ancient artworks into new, virtual contexts. The innovation of this project resides in the student use of digital technologies to facilitate the staging of interactions between viewers and objects, creating a complex interplay between original, digital model, and printed replica in various spaces and modes—the museum gallery, a new space viewed through a smartphone, or an immersive virtual reconstruction.

The educational practices embedded for this project were guided by multiple components including: 1) program and course student-learning outcomes within the art history and classics BA programs 2) previous research undertaken by the authors in their respective fields of art history and digital education 3) emerging research and literature involving digitization within education 4) theoretical frameworks of historical preservation 5) and previous implementation of a similar project led by the authors (see footnote 1). The collaborative, pluralistic, and hands-on approach to the study of ancient art provided the most profound outcomes for students involved in the Animating Antiquity Project, as undergraduate and graduate students engaged in traditional and emerging methodologies associated with museum work. The project therefore informed the course workflow, including the weaving of content-specific lectures and classroom discussions, technical workshops with project partners, visits to the museum, student conferences, and several project assignments. The incremental design of coursework allowed students to create and present what they learned in different ways while facilitating instructor feedback and assessment. Through the creation of an art historical dossier, undergraduate student teams gained knowledge in interpretative analysis and research of primary and secondary sources, demonstrated their understanding of art historical terminology, and effectively synthesized their findings through documentation, in-class discussions, a project website, and a final presentation. The digitization and fabrication of antiquities gave students the rare opportunity to interact closely with precious historical artifacts often overlooked within the museum. Students engaged in a variety of tasks including photographing objects and hands-on technical workshops to produce materials for museum patrons, including digital and tangible facsimiles of each artifact. The creation of interactive strategies for museum visitors (activities that encourage interaction with the 3D print of the digital model and create a dialogue between the 3D print and the real object) allowed students to become instrumental in providing solutions to remove visual or tactile restrictions in a visitor’s engagement with objects. The final element of the project involved cross-program partnerships, where graduate students leveraged the dossier, 3D digital models, and prints to design augmented and virtual reality applications and employ the technical knowledge from their coursework within a practice-based museum context.

Many of these digital technologies and pedagogical approaches have been deployed in museum and higher education institutions over the past few years (Balletti, Ballarin, and Guerra 2017; Flynn 2018; Grayburn et al. 2019; Jeffs et al. 2017; Saunders 2017; Schofield et al. 2018; Younan and Treadaway 2015). Similar pedagogical approaches that align with this project address: the handling of objects, transformations in interpretation, the recontextualization of heritage, and approaches to digitizing, editing, and fabricating 3D digital heritage. At the Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, an initial partnership between the schools of Industrial Design and Classical Studies used 3D scans and prints of antiquities to lessen students’ fear of handling objects by having them recreate the original function of the object (Guy, Burton, and Challies 2018; Victoria University of Wellington 2017). At the University of South Florida, undergraduate students participated in a crowdsourcing project to digitize heritage artifacts at the Archaeological Museum of Syracuse and create digital storytelling guides (Bonacini, Tanasi, and Trapani 2018). For almost a decade, Duke University’s Wired! Lab for Digital Art History & Visual Culture has transformed its program offerings to respond to digital technologies within the fields of art and architectural history, involving students in the digital reconstruction of heritage in a variety of contexts (Lanzoni, Olson, and Szabo 2015; Wired! Lab 2019). Recent research (Di Franco et al. 2015; Pollalis et al. 2018) has also addressed hands-on engagement with digital and 3D printed objects from the perspective of undergraduate students. As such, digital technologies within art history and classics curricula have spurred the transformation of higher education practices.

Finally, this project was guided by conceptual frameworks that address the complex relationship between humans and objects. Material culture studies have highlighted the central role of objects in human thought and action (Hicks and Beaudry 2010; Tilley et al. 2006). Specifically, thing theory argues for the active role of objects in defining human actions, giving something inanimate a rich biography and social life (Appadurai 1986; Brown 2001; Kopytoff 1986). Within the project, the artifacts were central actors in the design of the course assessments, the project components, and the student interaction with the antiquities. As student teams advanced throughout the project, the artifacts adopted new meanings through content generated by the students. Students were encouraged to make historical inferences about these objects to develop an original narrative about their history. As a result, the relationship between students and the objects was multifaceted and symbiotic, as objects interact with people and other objects to produce unexpected effects, strengthening or redefining pre-existing social or cultural relationships, or forging completely new connections (Mathews 2015). Furthermore, a significant outcome of this project was the incorporation of graduate students, who were encouraged to present their perspective on the role of the museum, its objects, and visitors. The interaction between people and objects therefore locates artworks in a constant state of redefinition as they engage with human actors in different spatial and temporal contexts (Figure 1).

This paper will outline the implementation and outcomes of the Animating Antiquity Project, addressing the key components of the project—the creation of an art historical research dossier, 3D digital models of ancient artworks, prints of 3D models, interactive strategies for the printed models, and a website presenting student research—in chronological order. A discussion of the creation of an art historical research dossier and digital 3D models for eight artworks in the Lowe Art Museum will be followed by a description of the varied applications of these core materials for interactive strategies that forged creative connections between ancient objects and modern viewers. This paper therefore seeks to demonstrate the rich and multifaceted relationships between people and objects that were forged through the use of digital technologies in the museum and classroom and share the pedagogical methodologies and outcomes associated with this project with the wider academic community.[1]

Art Historical Dossier and 3D Digital Models

Art historical dossier

The research conducted for the art historical dossier served as the first reanimation of ancient artworks in the Lowe, as the students began to understand the role that objects like glass vessels, ceramic wares, and portrait sculpture played in the ancient world. In their present configuration, the antiquities at the Lowe Art Museum reside in glass display cases with minimal background information and limited opportunities for visitor interaction. In order to foster a deeper understanding of these antiquities, students conducted art historical research on the eight objects chosen for 3D modeling and compiled that research in digital dossiers. The research focused particularly on the function and context of the artworks, as all ancient art served a purpose, be it political, religious, economic, or social. The research materials consulted by the students were eclectic in nature, given the lack of documentation on these specific objects. Students consulted dossiers on file at the Lowe Art Museum, art historical materials and practical guides from other museums and cultural organizations, scholarly books and articles, and web-based resources to understand and contextualize these ancient objects. The analysis of the antiquities began with a basic physical description, extracting visual information from the object itself. Then the students delved deeper into the history of ancient Greece and Rome to understand how these objects functioned, where they would have been placed and used, and how they would have been perceived by ancient audiences.

The subdividing of the written elements into thematic units facilitated the writing process. Students could concentrate on one topic at a time—function, iconography, context—and also review peer feedback that they could revisit and revise (Carless and Boud 2018). In the final stages of the dossier’s creation, the students worked on the text as a whole, making it flow as a seamless narrative, omitting redundancies and focusing the text on a particular theme related to the object itself. The preparation of the art historical dossier served a number of purposes: familiarizing the students with objects and their meaning in original contexts; creating the foundation for student-generated interactive strategies; and providing background information on the objects for visitors to the Lowe Art Museum. This original research conducted by the students provided a key outcome of the project, as most of these objects have not been studied in a systematic manner. The Canosan vase, for example, is a fairly common object, but this type of pottery has not been addressed extensively in the scholarly literature (Figure 2). In the absence of basic data, students researched comparable objects to make scholarly inferences about the artworks in the Lowe, collecting comparative materials with which to support their conclusions. The completed art historical dossier consisted of the following elements: a document presenting a visual description of the object and discussing its form, function, and original context; a photograph of the object; the 3D digital model; and images of comparable artworks. This research dossier was shared on Google Drive so that all the students devising interactive strategies would have access to this important contextual information.

In the final phase of the project, the dossier was uploaded onto a website that serves as the public portal to the research project [https://www.animatingantiquity.net]. Students were encouraged to review the Spring 2018 digital dossier (see footnote 1) as an ‘exemplar’ to illustrate assessment expectations (Carless and Boud 2018). Using WordPress, students created posts for each of the eight objects featured in the class project (Figure 3). Once uploaded to Sketchfab (a web platform for hosting and viewing immersive and interactive 3D files), the digital model was embedded within the post so that visitors could review still photographs and interactive 3D models while reading the text. The content of the website is accessible in the immediate context of the museum itself through a tablet mounted on a pedestal next to the artworks on display, so visitors can gain knowledge about the object while viewing it firsthand and performing the interactive strategies described on the website.

3D digital models of ancient artworks

In addition to the dossier, the creation of the 3D digital models profoundly influenced new interpretations and re-presentations of the objects (Kalay 2008, 8). Harrison (2015) proposes that heritage is inseparable from the interconnected relationships between social, political, and environmental issues. The 3D digitization process and the digital and fabricated objects invited conversations with students about conservation, management, and ethical implications of heritage artworks. As the fragility and antiquity of the artworks limited engagement with them, students were tasked with the design of digital and physical reproductions for the public to touch. The process of photographing the objects introduced students to the careful protocols established by museum staff for handling antiquities in order to ensure their proper conservation. Indeed, students contributed to the conservation of these artworks by creating 3D digital versions of the originals and compiling a set of photographs that documented the current state of the object. The ethical implications connected to fabricating artifacts were also discussed with students, encouraging them to consider the implications of creating digital copies of original artworks and the ways in which they could alter the meaning of the ancient artworks (Colley 2015).

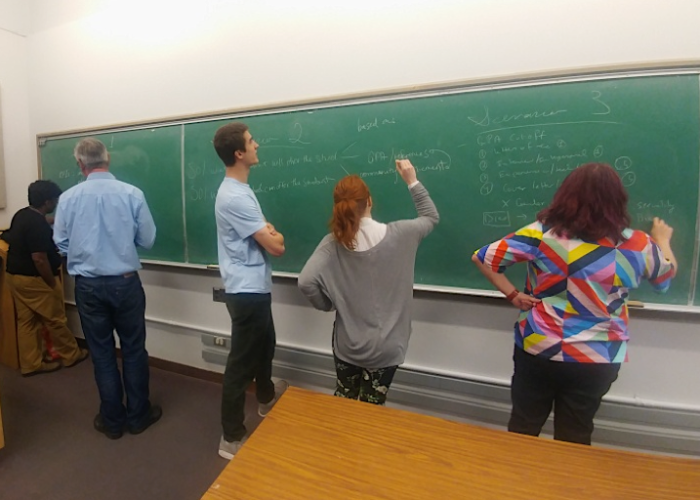

Students created the 3D digital models in a multi-step, group-based, collaborative process, in which tasks related to the various components rotated through each student group. Everyone contributed to all the interrelated parts and the students themselves were responsible for the completion of the digital model. Objects were selected based on their applicability for photogrammetry, and students created the 3D models of these artworks in three 75-minute hands-on workshops. First, the photogrammetry session at the Lowe Art Museum allowed students to capture multiple photographic viewpoints of the objects outside the display case, transforming how they usually interact with artworks. Eight students (two from each group) served as “digital preservation experts,” engaging with museum staff during the session as collaborators in the photography process. Museum staff installed, handled, and rotated the pieces while students determined the most effective ways to capture each object (Figure 4).

Students were provided some initial guidance and allocated an hour to capture the artworks. They checked the assembled equipment for any discrepancies, decided which object they would photograph, communicated with the museum staff to place objects, prepared and tested the camera settings, and completed four 360° rotations to ensure adequate overlap of focused photos at multiple camera angles to capture complex sculptural contours.[2] They then uploaded the files to a shared Google Drive folder.

Post session, two different students per group took the lead in editing raw photos, exporting them for photogrammetric processing using Autodesk ReCap Pro Photo. Once processed and downloaded, the files were reduced in size and exported for students to edit with Autodesk Meshmixer. Two modeling sessions completed the process of creating the 3D digital models. In the first session, two students per group edited mesh files, learning how to repair holes in the mesh, add surface texture to the model, and create a clean base. Students were encouraged to interact with the artworks in the digital realm, dismantling the object, creating new shapes, sculpting and adding textures to the reconstructed artwork. In this part of the process, emphasis was not placed on absolute accuracy, but rather on an authentic presentation of the digital object. With help from the authors and student assistants, timely, personalized feedback (Carless and Boud 2018) was shared with each student to prepare for the second modeling session in which further editing tasks were performed to prepare the files for uploading to Sketchfab and for 3D printing.[3] Once the 3D models were completed, the authors uploaded the .OBJ files onto Sketchfab. Students then created annotations for the digital models, noting aspects of the object’s iconography, material, and technique in short texts that can be read while manipulating the model (Figure 5). The publishing of the annotated models on a well-known website platform constituted another reanimation of these antiquities, as the digital model and its descriptive annotations bridged the distance between visitors, students, and the wider public audience.

Student-Generated Applications of Art Historical Research and 3D Digital Models

Reconstructing artworks through 3D printing

The 3D prints actualized the premise of the Animating Antiquity Project, bringing alive the culture of ancient Greece and Rome through a recontextualization of ancient artworks while creating new, contemporary connections between people and objects. The digital models themselves served an important didactic function, providing museum visitors with a more comprehensive understanding of an artwork through the manipulation of the digital model (Jeffs et al. 2017), but they also served as the basis for creating prints of the models that could be handled in the museum gallery. Complementing photographs and the digital model, the 3D print provided a third visual manifestation and reanimation of the object, replicating the art object in an accurate manner through its size and material. The printed replicas were painted to recreate the decoration on the artworks and provided viewers with tactile access to the objects. In museum settings, 3D prints of artworks allow visitors to engage with art in a more intimate way, complementing the original works in the display case and providing opportunities for blind and visually impaired visitors to experience art objects (Di Franco et al. 2015; Henderson 2018; Nancarrow 2017; Sportun 2014; Williams 2017; Wilson et al. 2018).

The 3D printing of digital models was essential for the interactive activities described below. The printing component was ambitious and interdisciplinary in scope, with a number of individuals, spaces, and institutions contributing to its successful completion. The digital models were prepared for 3D printing by students in Meshmixer with additional refinements made by the authors. Digital versions of vessels, for example, required thickened surfaces for structural integrity or were hollowed out so that they could be printed as vessels. After the first modeling session, ‘draft’ 3D models were printed at a reduced scale in polylactic acid (PLA) filament for students to handle, evaluate, and employ in devising interactive strategies (Figure 6). The remaining modeling edits and student-generated strategies informed the number, scale, and structure of the 3D prints.

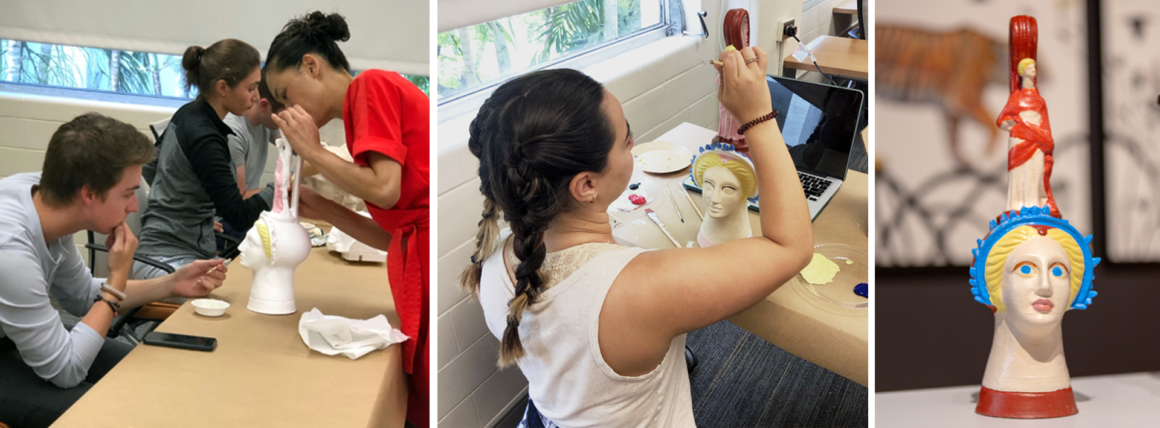

The printing workflow entailed dividing the objects between makerspaces in the College of Engineering, the Department of Art and Art History, and an Ultimaker 3 managed by Academic Technologies.[4] As the Engineering printers could also accommodate larger-scale objects, most models were printed to emulate the scale of the original artwork.[5] Prints were made using various PLA filament types, with a marble-like filament emulating the crystalline structure of stone sculpture, while wood-fiber and terracotta-colored plastic reproduced the original materials of other ancient objects. Printing times could vary from three to thirty-six hours per object, so the completion of these prints was scheduled over a month time frame, anticipating printing errors and print queue issues while accommodating other users on campus. Once the prints were ready, students prepared models for painting. Some models remained unpainted, as the PLA imitated the original material of the artwork, but others had their original polychromy “restored” or were painted to more closely emulate the original decoration (Figure 7). Students in this phase of the project could interact freely with the models in ways that would be impossible with the original artwork, emulating the original use of the objects in their handling and manipulation.

Undergraduate student strategy: Restoration of the Canosan funerary vessel

The 3D prints provided the opportunity for an imaginative reconstruction of the object. Instead of copying the current state of an artwork, prints can recreate the original, often vibrant, decoration of ancient objects. The Canosan vessel print, for example, displays the bright primary colors that would have characterized this funerary offering in its original state (Figure 8). The comparison between the modern copy and the artwork itself presents significant historical information about material culture in the ancient world.

Undergraduate student strategy: Recreating Theseus and the labyrinth

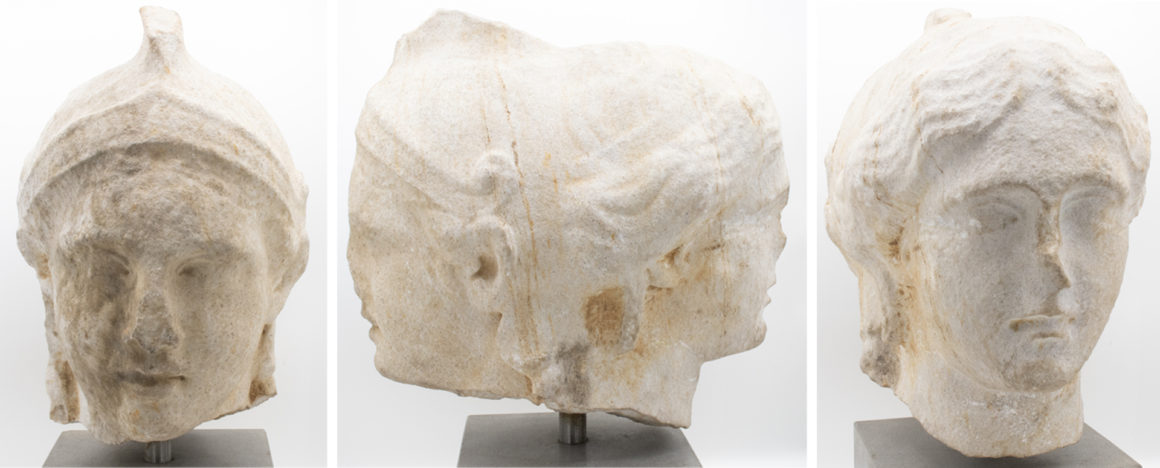

Student-generated strategies strove to combine three versions of the same object—original, digital model, and 3D print—in order to animate the artwork for museum visitors. These interactions could highlight the form and iconography of the object or shed light on its function and original context. The interactive strategy devised for the double-headed sculpture of Theseus and Ariadne focused on the duality and complementarity of the two figures portrayed (Figure 9).

For the 3D print, the students separated the heads to emphasize the distinct characteristics of each figure but also the complementary nature of the pair. Added to the Theseus print was a maze representing the labyrinth that he had to negotiate with the help of Ariadne to kill the Minotaur. Ariadne gave Theseus a ball of thread so that he could trace his way out of the maze. In the gallery activity, a stylus attached to a string on the Ariadne side traces the path of Theseus through the maze, demonstrating the cooperation between the couple that helped them destroy their monstrous adversary (Figure 10). Color-coded pins inserted into the print provided information about the myth in stages so that viewers can follow the path of the protagonist and discover the intertwined nature of these two mythological figures.

Undergraduate student strategy: Simulating the calyx krater’s function at the symposion

A third interactive strategy recontextualizes the calyx krater and the role it played in the ancient Greek symposion, a gathering of Greek men who engaged in conversation, listened to music, and enjoyed entertainment while drinking wine mixed with water. The mixing of the two liquids was essential for ensuring the longevity of the symposion and displayed the civilization of the Greeks, as only “barbarians” drank unmixed wine. The krater was the vessel used to combine water and wine and was thus an indispensable component of the symposion itself. The imagery on this krater alludes to its function, representing the god of wine, Dionysus, and his followers in a procession (Figure 11).

The interactive activity recreated the symposion environment by distributing a number of smaller drinking vessels to the “participants” of the gathering while demonstrating the dilution of the wine central to this ritualized activity. The interactive strategy highlighted the function of the krater while elucidating the iconography of the vessel (Figure 12).

Interdisciplinary work by MFA students

Though the content of the Animating Antiquity Project was devised in the context of an undergraduate course, MFA students from two different schools designed and implemented their own creative engagements with 3D models and prints using the art historical dossiers and digital models created by the undergraduates. One project emerged through a graduate student’s exploration of makerspaces across the UM campus and the potential of 3D printing as a creative sculptural medium. Two additional projects developed through partnerships with students in the MFA program of Interactive Media at the School of Communication. Enrolled in courses dedicated to the study and implementation of AR and VR technologies, these graduate students used the content created by undergraduate students to design interactive approaches with the Lowe antiquities. The undergraduates, then, served as the experts in terms of knowledge of the art objects themselves and in terms of the creation of raw digital data. Through shared Google Drive folders, graduate students could access all the work folders and employ the raw materials compiled by the undergraduates in innovative technological formats.

MFA student project: Experimentation with 3D modeling and printing (Monica Travis)

The greatest experimentation with printing materials took place with the reproduction of a Hellenistic theater mask by Monica Travis, MFA student in sculpture in the Department of Art and Art History. The theater mask is a bronze object, and Monica wished to print it in metal to emulate the original material. The Johnson & Johnson Lab in the College of Engineering possesses a metal 3D printer that produces parts with titanium powder, and these advanced facilities provided the opportunity to print the bronze theater mask in a metallic medium, that of titanium. This printer is often used for the prototyping of parts, so the printing of an art object constituted an innovative application of its capabilities. Monica undertook a meticulous preparation of the file for printing, editing photographs in Adobe Photoshop and processing them in Agisoft Metashape, an advanced photogrammetry tool. The modeling application Rhinoceros was used to clean up the model and prepare it for printing. A test print was performed using a Lulzbot Taz 6 in the Department of Art and Art History before queuing it on the titanium printer (Figure 13). This project provided an opportunity for Monica to innovate in both the methods and materials used; she experimented with photogrammetry, photographic editing, and modeling tools to produce a print using materials not often employed in 3D printed artworks.

MFA student project: Antiquities in real world contexts using augmented reality (Jinqi Li, MacKenzie Miller, Laura Miller, Aishwarya Navale)

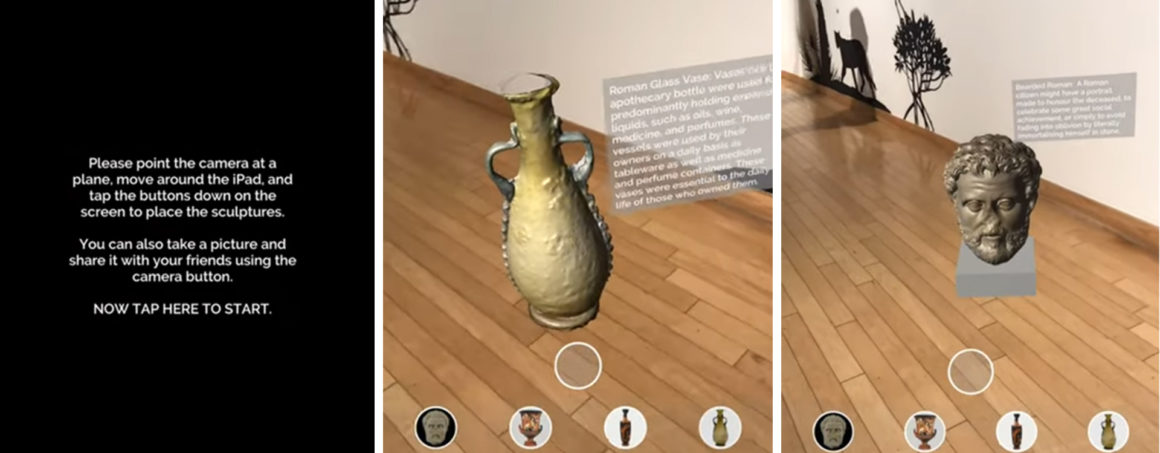

In the context of a course offered in the School of Communication at the University of Miami, graduate students from the MFA Interactive Media program created two AR applications using the student-generated digital models of the Lowe antiquities.[6] The concept behind both apps was to enhance visitor interaction with the objects using a smart device (Marques and Costello 2018). The first AR application allows museum-goers to observe the antiquities up close in 3D. Users employ a brochure that serves as the platform for the experience, allowing them to use the app anywhere. The brochure possesses four recognizable image targets that trigger the AR program when a device’s camera is directed at them (Figure 14). When the image target is detected, users view the rotating digital model on their mobile screen, supplemented with audio narration addressing significant information about the artwork. To create the first application, the students used Vuforia Augmented Reality SDK in Unity 3D to enable the image target detection of the artifacts. Dr. Mathews recorded the audio that was used in the application, and a rotation effect was added so that the viewer could see the artifact from all angles. Lastly, the application was exported to a mobile phone using Xcode.

The second application enables museum visitors to take the artworks home with them virtually, observe the objects in new contexts, and share their experiences on social media platforms. Users of this application scan a room and then project the 3D model of the object onto that space. The object can be resized and moved around the room to the ideal virtual setting, and the user can then photograph it and share it. The students used ARKit SDK in Unity 3D to make an application where a virtual object can be placed in the real world. A menu allows the user to choose the object they would like to place in a new real-world context (Figure 15). Both of these AR applications used digital models and art historical research to connect people and objects through interactive experiences. The users of these AR applications learn more about the objects in a personalized manner, employing a smart device as a tool to display and manipulate the 3D models, place the antiquities in novel contexts, and share their interactions with others.

MFA student project: Feeling Antiquity in virtual reality (Lorena Lopez)

This virtual reality (VR) experience attempts to show the myriad ways in which immersive environments can enhance a visitor’s understanding of artworks in a museum setting by emphasizing the power of touch. Both museum and VR experiences generally lack a tactile component, that is, the ability to touch objects in real and virtual spaces (Candlin 2010; Candlin 2017). In the Feeling Antiquity experience, visitors can interact with a 3D print in a virtual realm. The object selected for the VR experience was the calyx krater, a vessel that was used to mix wine and water in the context of the symposion (Figures 11 and 12). As part of a summative project to demonstrate her knowledge and construction of virtual worlds, Lorena Lopez used the art historical dossier created by undergraduates to study the physical setting of the symposion, a space called an andron that was used exclusively by males. Using the Unity Game engine and its asset store, she constructed the 3D scene where men would gather for the symposion and hold the krater (Totten 2014). Through an HTC Vive Pro VR headset, the viewer was immersed into the ancient Greek space of the andron. Once there, the user of the headset could interact with a full-scale print of the calyx krater, touching and picking up the printed model of the vessel using the handheld controllers (Figure 16). The virtual visitor was not only transported to the ancient past, but they could reach out and actually touch an object within the space of the andron. In a museum setting, the sense of touch is generally subordinated to the visual, as visitors are discouraged and prohibited from touching artworks (Di Franco et al. 2015). VR can break down these barriers and allow museumgoers to engage art with more than just vision, handling ancient artworks in the same way that they would have been used in the past. There are great, but still untapped, possibilities in the realm of haptic gloves and suits, though handheld controllers were used in this experience in the interest of time (Needleman 2018; Hall 2016). These VR technologies can animate places and objects that are distant geographically or no longer extant, integrating touch into an interactive and immersive environment that complements and enhances a museum experience.

Conclusion: Outcomes and Reflections

In the context of the spring semester course, students successfully completed all the stated objectives: the creation of an art historical dossier, a digital model, a 3D print, strategies for visitor interaction with the 3D print, and a website. What was actually gained from this experience, however, was far richer. The interdisciplinarity and interactivity of the work conducted established meaningful connections between the students and the objects they studied. Students were exposed to numerous ways in which research and digital content could reanimate ancient objects. They also gained invaluable, hands-on practice with various digital technologies and processes, helping them determine where their personal interests and talents lay, be it in painting, 3D modeling, printing, or photography. The implementation of this project did pose some challenges, as the production schedule for the multiple components had limited flexibility, and a less-condensed time frame would have allowed for more exploration and mastery of research and technical skills. The display of 3D prints and implementation of XR technologies also raise ethical and logistical issues concerning the use of digital technologies in traditional museum spaces (Colley 2015, 17). Where do you stage such interactive experiences, and who provides oversight and monitoring? AR applications can be integrated easily into museum galleries through the use of smart devices, but VR often requires expensive equipment, space for movement, and timed sessions (Meier 2017). Furthermore, while the 3D/XR digital assets created in this project aimed to align with existing imaging and digital preservation practices (Alliez et al. 2017; Bedford 2017), limited control of metadata is a topic being addressed by open communities and experts (Moore et al. 2019; Rossi, Blundell, and Wiedemeier 2019). Once these practical challenges are addressed, however, myriad possibilities exist for the use of digital products and technologies in museum and undergraduate education, as 3D prints and their interactive applications can play a central role in the pedagogical mission of museums, encouraging visitors to devise their own strategies for connecting to people and objects from the ancient past.